Money making: A brief history of currency from the British Museum

- Published

A history of money in five objects

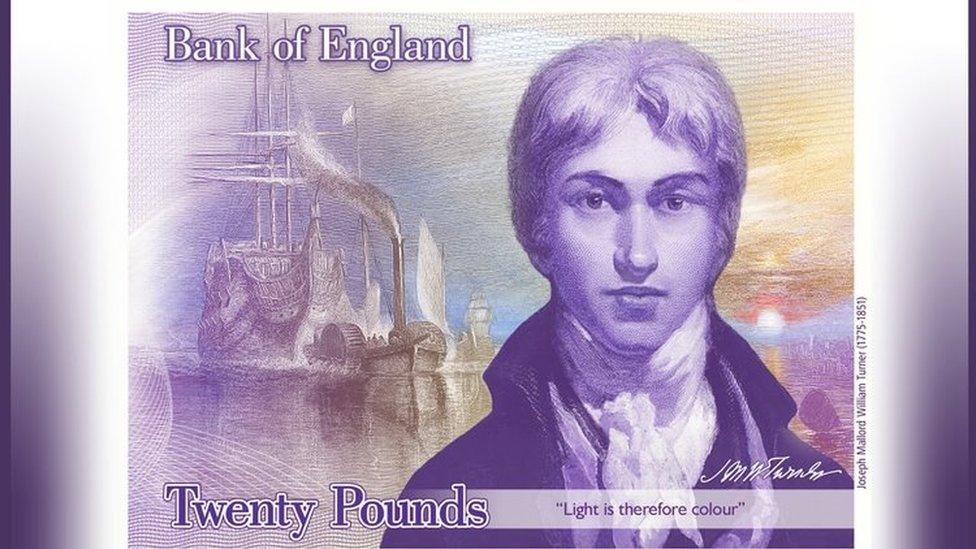

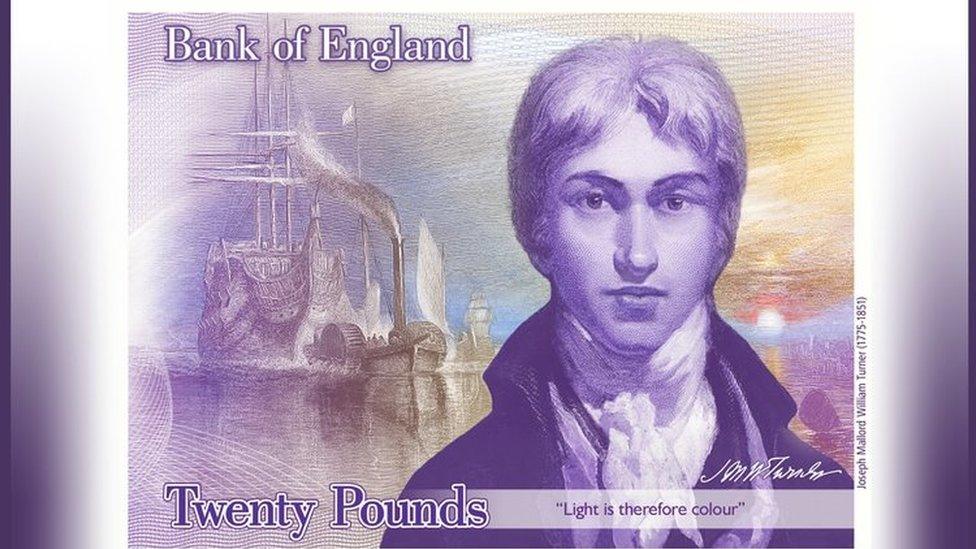

Debate has begun over the choice of JMW Turner to be commemorated on a Bank of England banknote.

The public was included in the choice of nominations for the honour of appearing on the next £20 note, to enter circulation in 2020.

As with the new £5 and £10 notes from the Bank of England, being introduced this year and next, the £20 note will be made of plastic.

This extends a rich history of changing currency in the UK and worldwide.

The new £20 banknote will feature a self-portrait of JMW Turner and one of his best works

The plastic notes - starting with the new £5 note featuring Sir Winston Churchill due to be issued in September - will eventually replace cotton paper notes, which have been used for more than 100 years.

In many ways, this is a significant change in the way money is produced, not least because a Bank of England banknote will survive a spin in the washing machine for the first time.

However, there are many other revolutionary developments in the way money has been made over many centuries.

Ben Alsop, curator of the Citi Money Gallery, external at the British Museum, and Mieka Harris, education manager for the gallery, offer a snapshot of this rich history - with the help of five objects from the gallery's collection.

Coins, as we know them

Although irregular in size and shape, these early Lydian coins were minted to a strict weight-standard

This coin made from electrum - a natural alloy of gold and silver found in riverbeds - is one of the earliest examples of coins, and the beginnings of the Western tradition of coinage that is still going strong.

It was minted in Lydia, in modern day western Turkey, in the 7th Century BC, making it more than 2,500 years old.

These coins, featuring a lion's head, were of a consistent weight and purity. As a result, they held a value that allowed them to be used in cross-border trade - replacing the idea of two commodities effectively being swapped between traders.

The tiny coin was of significant value, so was used in high-level trade, as gifts between rulers, and as payment to mercenary soldiers.

The vast majority of the population would never see one, and continued to trade without coins - as had been the case for cities and empires for more than 2,000 years. Bartering, for example, still ran in parallel with trading using coins.

Spade or money?

Chinese spade money alongside a 10p coin

Throughout history, coins have looked very different to the money we recognise today.

This hollow-handled spade money was used in China in the early 6th Century BC, when the country was made up of a number of separate states

In order to inspire confidence among the merchant classes to use this abstract concept of bronze money, it was shaped as an agricultural tool - an item recognised by these people, rather than an alien, round coin.

Coins shaped as knives were also produced in China around 200 years later, as this was a shape recognised by those involved in warfare.

Weight was much more important that shape in terms of value.

Although its use was more widespread than the Lydian coins, the use of coins as currency did not filter down to the population at large until Roman times.

The birth of banknotes

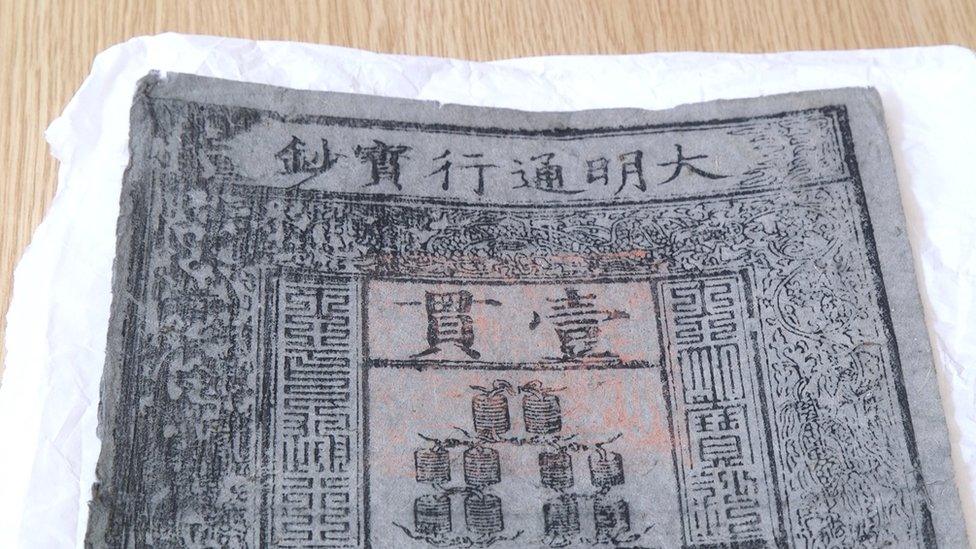

This Chinese "paper" bank note is actually made from the bark of a tree

The earliest banknote in the British Museum's collection is this grandly named Great Ming circulating treasure note from the 14th Century.

It is an early example of "paper" money carrying a value. In this case, the one guan note is worth 1,000 coins, as can be seen from the illustration on the 34cm by 22cm note. It is actually made of mulberry bark.

"People started to call it 'flying cash', partly because of its convenience across high-level trade, but also because it no longer had the weight to it that coins would have had," says Ms Harris.

"So if you were not holding it properly, it could potentially fly away."

Backed by the central authority, it also features a border of dragons, and an inscription that warns against counterfeiting.

The warning seems to have been ignored. Owing to counterfeits and inflation - which rose as printing money became easier - China stopped issuing paper notes in the early 15th Century and did not start again until the 19th Century.

Local currency

In the 17th Century, the civil wars in the British Isles saw the rise of locally produced coins or tokens

When the British Isles were gripped by civil war in the 17th Century, there was huge instability and a lack of small denomination currency.

Small traders and other establishments stepped in when the central authority was unable to provide this coinage, by issuing their own tokens.

This 17th Century token was issued, according to the inscription, by John Ewing, who traded near St George's Church in Southwark.

He was a tobacconist, hence the image of a monkey smoking a pipe. Customers could use this token in his store, but other local traders may have accepted it, too.

This private production of money was in many ways a forerunner to local currencies seen today such as the Brixton Pound and the Bristol Pound, as well as cryptocurrencies or digital currency such as Bitcoin.

However, these tokens were not used for long. A Royal proclamation, following the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, clamped down on their production.

Age of plastic

In 1958, Bank of America launched its BankAmericard - the first successful modern credit card

Although money is inherently conservative in nature in order to be accepted by the general population, there have been some revolutionary developments.

One was the birth of the credit card, even though credit and debt have existed for as long as money itself.

This particular card is an early example from the US, from the 1960s.

Credit accounts were already common in individual stores, but credit cards allowed people to use one card to shop on credit across the numerous stores and not have to carry notes and coins.

"To get people using them, they were mailed out to people who had not asked for them, just to try to encourage people to use this new form of payment," says Mr Alsop.

This was not particularly scientific, so there were examples of credit cards being sent to toddlers.

There was no automation in the credit card, as is the case today, so shoppers would hand over the card to a shopkeeper who would make a telephone call to a bank. That bank would then check with the shopper's bank by phone and eventually the transaction would be authorised.

- Published22 April 2016

- Published2 September 2015

- Published22 May 2014

- Published6 November 2015

- Published18 December 2013