Harriet Tubman: Former slave who risked all to save others

- Published

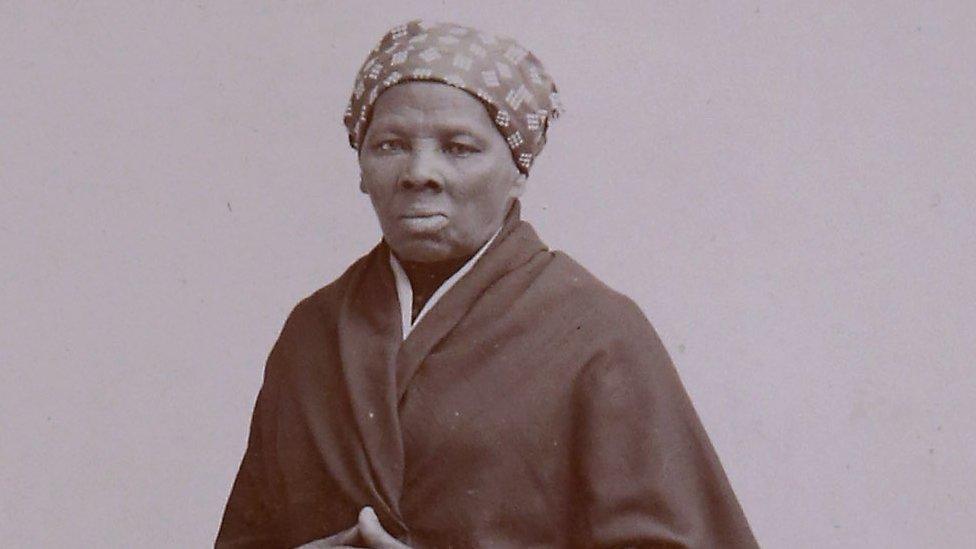

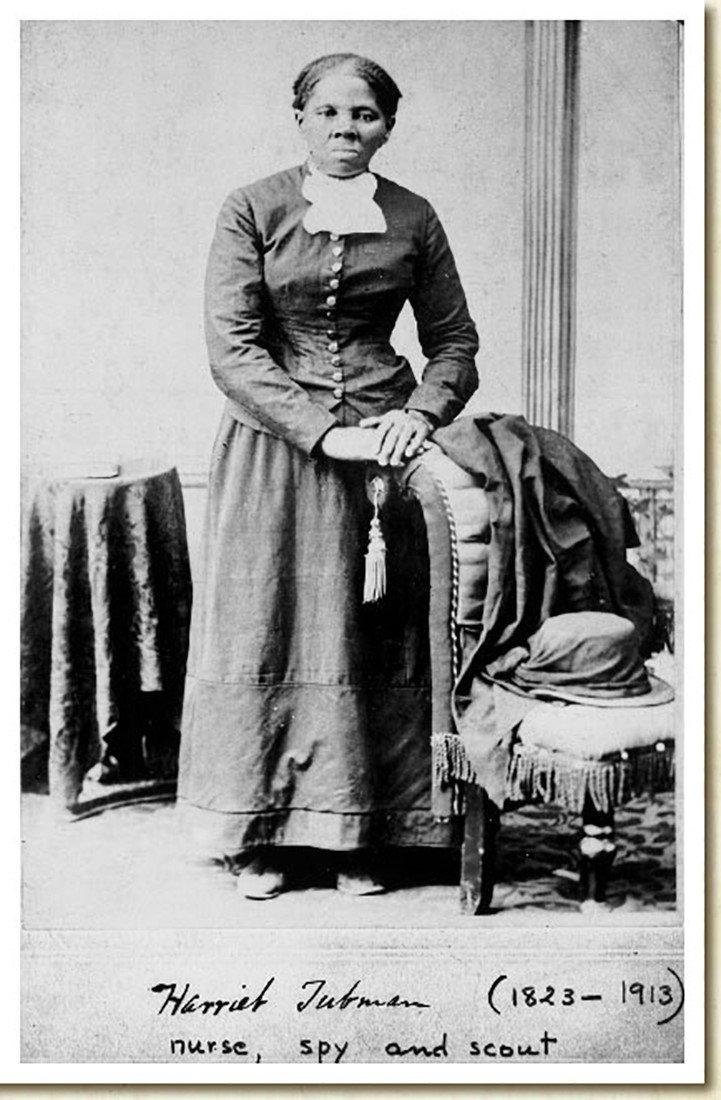

Harriet Tubman served as a spy and a nurse for the Union during the Civil War

Sometime in mid-October 1849, Harriet Tubman crossed the invisible line that bordered the state of Pennsylvania.

Tubman, a slave and later prominent abolitionist who has been chosen as the face of the new $20 bill, had escaped a plantation and was partway through a near-90 mile journey from Maryland to Philadelphia, and from bondage to freedom.

She left the plantation, in Dorchester County, Maryland, in September and travelled by night. Her exact route is unknown, but she probably walked along the Choptank river and journeyed through Delaware, guided by the North Star.

Years later, she recalled the moment she entered Pennsylvania, where slavery was illegal: "When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven."

In the years that followed, Tubman returned again and again to Maryland to rescue others, conducting them along the so-called "underground railroad", a network of safe houses used to spirit slaves from the South to the free states in the North.

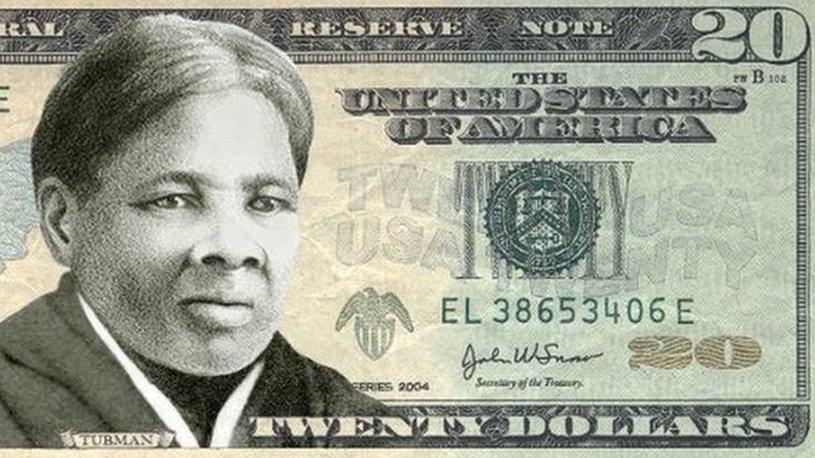

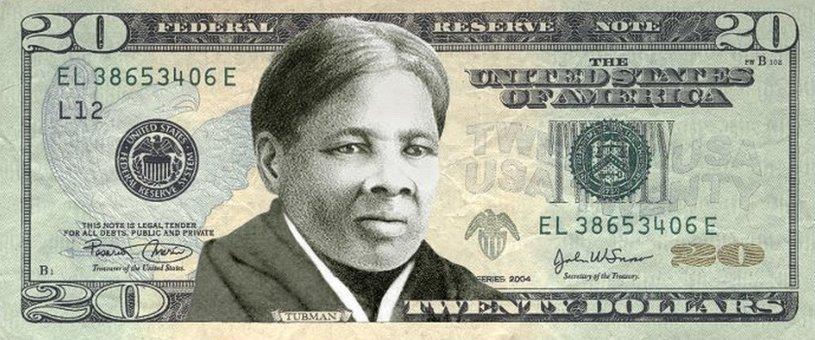

A mock-up of the new $20 note

Later, she became a Union spy during the Civil War, a prominent supporter of the women's suffrage movement, and a famous veteran of the struggle for the abolition of slavery.

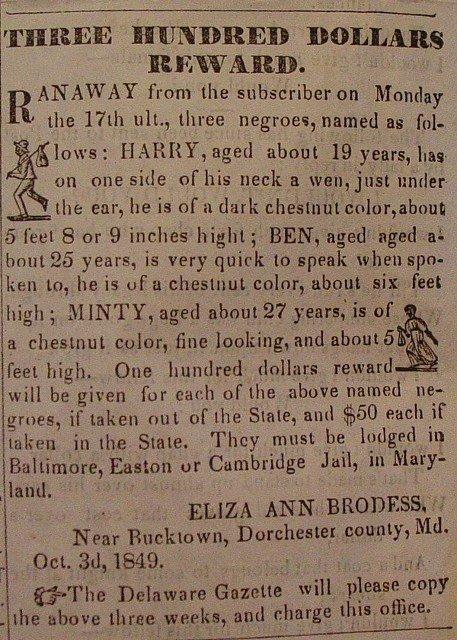

But in September 1849, aged 27, Tubman was an unknown slave, uncertain about her future in the wake of her master's death. Fearful of being sold further south, she gathered her two younger brothers, Benjamin and Henry, and on the night of the 17th they escaped.

With the help of their father, who had been granted his freedom, the three fugitives hid for three weeks. A notice published in a local newspaper offered a $100 reward for the return of each of them.

Scared of what lay ahead, Ben and Henry had a change of heart and returned. Tubman, with a steely determination that would come to define her, pushed on alone.

A daring escape

Harriet Tubman was the fourth of nine children born to two enslaved parents in Dorchester County, Maryland. Benjamin Ross and Harriet Rit named their fourth child Araminta - or "Minty" - Ross.

Minty grew up on the plantation, and as a teenager she was hit in the head by an iron weight thrown by an overseer at another slave. She was severely injured and went on to have seizures for the rest of her life, as well as "visions" which she believed were sent from God.

Decades later, in preparation for her escape from Dorchester County, Minty took her mother's Christian name and her husband's surname, to become Harriet Tubman. Her husband, John Tubman, a free man, stayed behind when she decided to escape.

Having made it to Philadelphia, Tubman found work as a domestic servant and began to save. In late 1850, she got word that her niece Kessiah Jolley Bowley, who was more like a sister to her, was to be put up for auction by Tubman's former owner. Bowley's two children, James and Araminta, were also to be sold. Tubman had her first rescue mission.

A newspaper notice offering a reward for the return of Tubman and her brothers

In December, she met Bowley's husband John in Baltimore and the two hatched a plan. John travelled to Dorchester County Courthouse and surreptitiously placed the winning bid for the three. Having smuggled them out before anyone realised, he sailed them up the Chesapeake river to Baltimore, where they met Tubman. From there, they made their way to Philadelphia and on to Canada.

Tubman would go on to help at least 70 people - family, friends, and strangers - escape slavery in this way, taking enormous risks with her own hard-won freedom. She travelled in a variety of elaborate disguises and armed herself with a revolver.

As word of her daring rescues spread, the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison nicknamed her "Moses", after the prophet who led the Jews from slavery in Egypt, and the name stuck.

In 1854, by then a veteran of the escape business, Moses finally freed her three younger brothers, Ben, Henry, and Robert. And in 1856 she rescued her parents, who had been granted their freedom but were suspected of helping others escape.

She had become a "powerful symbol for all Americans of the courage it required before the Civil War to confront slavery," says Fergus Bordewich, author of Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad.

The abolition movement was not, as many came to think, about "white people saving helpless black people", he says. Black people were crucial to its success and Harriet Tubman was "at the cutting edge of that".

Nurse, scout and spy

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 empowered slave owners to recapture slaves who had fled to free states, so Tubman helped to extend the underground railroad to Canada, where people could settle without fear.

It was there that she met John Brown, a radical abolitionist who had committed to using violence to overthrow slavery. In 1858, Tubman helped Brown plot a raid on a government arsenal in Harper's Ferry, West Virginia, with the aim of stealing weapons to arm slaves for rebellion.

Brown carried out the raid with 20 accomplices but was captured and later hanged.

When civil war broke out in 1861, Tubman worked as a cook and a nurse and then a scout and a spy, collecting information for the Union government from behind enemy lines. In 1863, she led Union forces in the Combahee River Raid, which liberated more than 700 slaves in South Carolina.

"I nebber see such a sight," she said later, describing the rescue. "We laughed, an' laughed, an' laughed."

"She was an illiterate woman of colour," says Catherine Clinton, author of Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom, "not only physically challenged but disabled by her race and gender. And she defied the power of slavery."

Written out of history

After the war, Tubman toured Eastern cities giving speeches in support of women's suffrage, drawing on her experiences in the fight against slavery, and became a prominent voice in the campaign.

She lived on a small piece of land in Auburn, New York, given to her by abolitionist Senator William H Seward. In 1869, she married Nelson Davis, a Civil War veteran, and in 1874 they adopted a baby girl, Gertie.

In 1903 she donated part of the land to the Church and in 1908 the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged, a home for elderly African-Americans, opened on the site. The brain injury she had sustained as a child was worsening with age, and in 1913 Tubman moved into the home named after her.

She died later that year, aged 91, surrounded by her family.

Tubman's efforts were well documented in her lifetime, but like many African-Americans she was written out of history in the decades after the Civil War, says Mr Bordewich.

She remained mostly a folkloric figure until after the civil rights movement in the 1960s, when the story of her contribution slowly resurfaced and was set down in school textbooks for generations to come.

When the new $20 note comes into circulation - in 2020 at the earliest - Tubman will be the first woman on a US banknote since Martha Washington briefly graced the $1 bill in the 1890s. It is a "triumph for the public recognition of African-Americans who struggled for freedom," says Mr Bordewich

Tubman will replace former President Andrew Jackson, a slave owner, on the front of the bill. Jackson will be moved to the back.

- Published18 June 2015

- Published13 May 2015