For Osborne, bad economic news could be good news

- Published

- comments

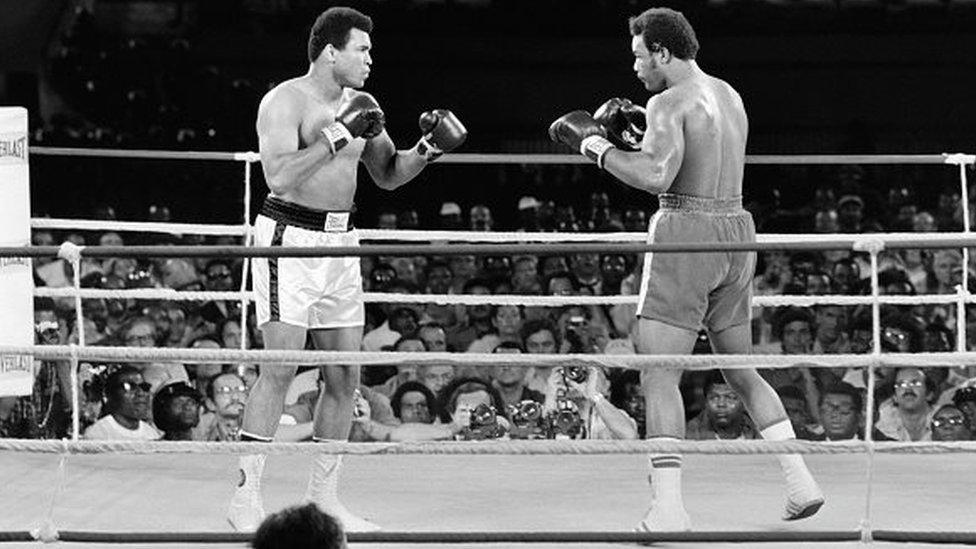

When Muhammad Ali beat George Foreman in 1974's Rumble in the Jungle it wasn't until the eighth round knock-out that everyone suddenly realised what Ali was up to.

His "rope-a-dope" strategy of letting the more powerful Foreman punch himself to a standstill resulted in Ali winning a fight many had predicted, and the first seven rounds had suggested, he would lose.

The best strategies are often only revealed in hindsight.

As a sharp observer of political strategy, a different George, Osborne this time, knows the value of long term planning.

Of having a strategy at the beginning of a fight that is only revealed at the end.

When everyone can say - "Ah, so that was what he was up to."

Tomorrow's economic growth figures are a case in point.

They are likely to show a significant slowing in the economy over the first three months of this year.

Most economists predict a growth figure for gross domestic product - approximately the amount of national income a country is producing - of +0.4%.

That compares to a figure of +0.6% for the same period last year.

Now cast your mind back to January.

In his first big speech of the year, the Chancellor spoke of a "dangerous cocktail of economic risks".

A slowdown in China, a slump in commodity prices and tensions in the Middle East were weighing on the UK economy, he claimed.

"It is precisely because we have not abolished boom and bust as a nation, that I need to go on explaining to the public that the difficult times aren't over, we have got to go on making the difficult decisions, precisely so that Britain can continue to enjoy the low unemployment and the rising wages that we see at the moment," Mr Osborne said.

At the time, many thought the Chancellor was getting his excuses in early for why the economy in 2016 was not going to perform as well as in 2015.

And why the Chancellor might miss his politically important deficit reduction targets.

But, four months on from that speech in Cardiff, a rather different perspective is beginning to emerge.

It is likely - in fact probable I would say after speaking to those close to Mr Osborne - that the Chancellor will claim "referendum uncertainty" as one of the reasons for the stuttering economy.

Because a stuttering economy feeds the risk agenda - Project Fear - those pro-remaining in the European Union have been mapping out.

And is, to an extent, good news for the Remain campaign of which Mr Osborne is a leading figure.

The question: Is referendum uncertainty really the reason for the economic slowdown?

On that the evidence is mixed.

The latest report from the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, published two weeks ago, said there was some evidence that investment decisions had been delayed until the results of the vote are known.

Commercial property deals have slowed and company takeover activity - often a spur to productivity gains and faster growth - have been postponed.

A survey of company executives by Deloitte revealed that levels of "financial uncertainty" were at a three-year high.

Against this stack of evidence, though, there are more fundamental issues than recent referendum risk which are affecting the UK economy.

Manufacturing growth is still anaemic, industrial production data are weak and exports struggling.

UK productivity improvement levels - one of the main drivers of growth - have still to recover following the financial crisis.

It is also worth remembering that though the uncertainty risk is rising now, tomorrow's GDP figure is for the first three months of the year.

David Cameron did not announce the date for the referendum until the end of February.

If the EU referendum outcome is weighing on economic sentiment, then expect a much sharper affect to be seen in the second quarter growth figures, to be released in three months time.