Nestle: Bottling water in drought-hit California

- Published

California is now in its fifth year of drought

Nestle extracted 36 million gallons of water from a national forest in California last year to sell as bottled water, even as Californians were ordered to cut their water use because of a historic drought in the state.

And the permit that Nestle uses to operate its water pipeline in the San Bernardino national forest costs just $524 (£357) a year.

That rankles with some residents and environmental groups, who want the US government to cut off Nestle's access to the water until an environmental study can be conducted.

Nestle has the legal rights to the water, and Arrowhead water has been bottled from springs here since 1894.

Yet the firm's permit to operate this seven-mile pipeline in the mountains expired in 1988, though since it pays its yearly $524, the licence is still considered valid by the US Forest Service and by Nestle.

However, activists consider the permit expired and the US government is now reviewing Nestle's licence. A public comment period has just closed and this month a federal hearing will consider the legality of the permit.

"The forest service should protect the forest," says Amanda Frye, a resident who's becoming known as a water rights activist. "A healthy forest produces a healthy population of people. We need the forest."

Remote pipeline

But bottled water is also healthy compared to sweet, fizzy soft drinks. And Americans are drinking more bottled water than ever - indeed water is on track to outsell other non-alcoholic soft drinks by 2017, says the Beverage Marketing Corporation.

The seven mile pipeline runs through difficult terrain

Nestle Waters' natural resource manager Larry Lawrence says the company has no plans to stop bottling water, largely because of public demand.

At the heart of the legal battle is Strawberry Creek, a remote area in the mountains, which would take hours to hike to. Mr Lawrence invited the BBC on a helicopter ride to the creek for an interview - and to show that it is vibrant, lush environment.

It took just seven minutes to get there in a helicopter, flying low through canyons following the pipeline as it snakes up the mountain to the creek.

"I don't see that evidence," Mr Lawrence says when asked if the creek were being deprived by the bottled water operations.

Oversight challenge

He speaks as we hike down to the small creek next to the pipeline, through poison oak and nettles. The water "is all collected naturally", he says, and the amount taken depends on the year and rainfall.

In 2015, it was 36 million gallons, compared with 28 million gallons in 2014, he says.

It is relatively lush and beautiful on the mountain, presumably partly due to recent rain. It snowed and hailed a bit while we were there in a sudden and much-needed April storm. But locals say it used to be a much healthier ecosystem.

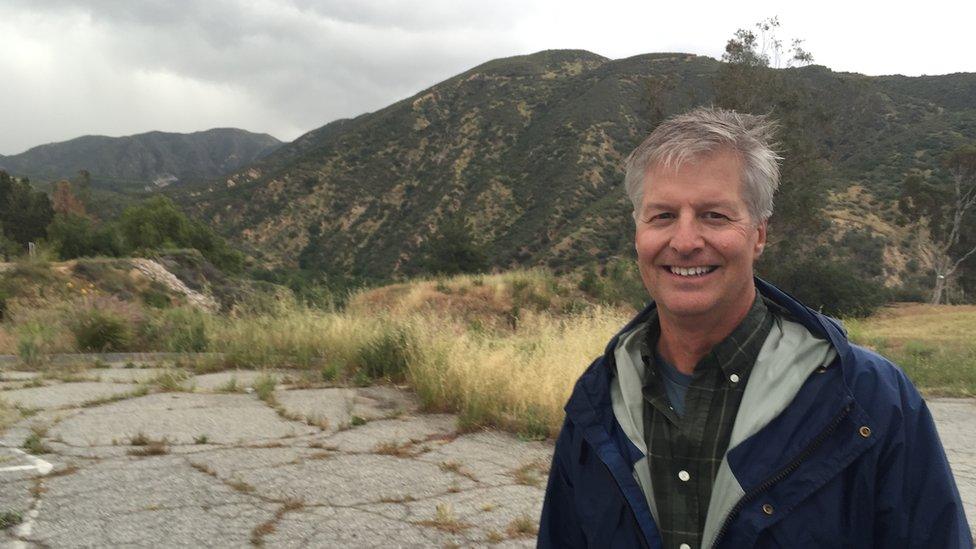

Nestle's Larry Lawrence says the company has no plans to stop selling the water it bottles from the spring

Gary Earney is retired from the forest service but used to be in charge of managing the relationship with Nestle. "I'm the only one who's ever hiked the length of the pipeline as far as I know," he says.

Bureaucracy and budget cuts in the US government are to blame for the lack of oversight, he argues.

The last time the forest service planned to review the Nestle permit in 2003, the area was devastated by a massive wildfire. Mr Earney retired a few years later, but he now supports the lawsuit and wants to see the forest service make up for past mistakes.

"This is not the only place in the world where people are fighting Nestle," he says. "In my opinion, Nestle is trying to corner the market on potable water and sell it."

He describes the forest service relationship with Nestle as "too chummy", a claim the forest service and Nestle dismiss.

Growing protests

Michael O'Heaney, executive director of The Story of Stuff, which is one of the groups suing Nestle, says the licence should be considered legally invalid as it has expired, and says Nestle is operating with little or no scrutiny.

"We were hesitant to sue the forest service. They are a beleaguered federal agency and they are so focused on wildfires," he tells the BBC. "We feel we've already accomplished something because they are reviewing it [the permit]."

California may bottle three billion gallons of water a year, but Los Angeles uses more tap water than that in a week

In the grand scheme of California's water problems, bottled water is a drop in the bucket. According to the International Bottled Water Association, about three billion gallons a year are used to make bottled water in California.

The city of Los Angeles, by comparison, uses more than that in a week in tap water.

But in a drought every drop counts, which is perhaps why there has been so much protest against Nestle in the past few years.

Mr Lawrence, who has been with the company for 13 years, says recent protests against Nestle Waters are unprecedented in California. He says the employees live and work in California and are as concerned about drought conditions as anyone else.

'I care about the creek'

US Forest Service hydrologist Robert Taylor says they have no idea how much water is too much to remove, because it's never been studied.

"We are not allowed to be arbitrary and capricious" in making decisions on Nestle's permit, he says.

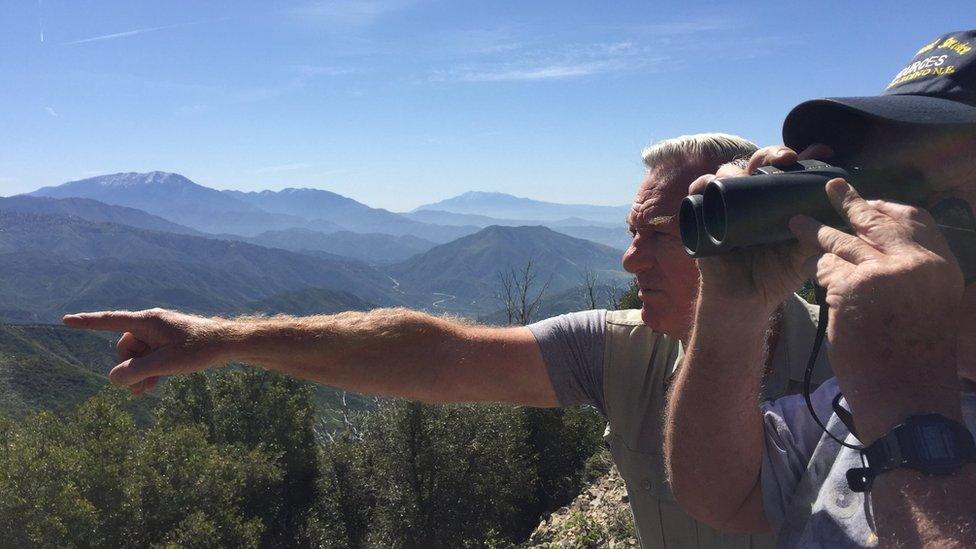

Retired forest service workers Gary Earney and Steve Loe (right) are critical of Nestle's operation in the San Bernardino national forest

Retired wildlife biologist Steve Loe, who worked at the forest service with Mr Earney and is also critical of Nestle's work on the mountain, says he feels he needs to speak out for future generations.

"I don't care about my legacy - I care about the creek and my family," Mr Loe says. "I have grandkids and kids that I want to leave a good planet for them, not a dead planet.

"This was the one area where I think I can have the most influence. That's why I'm here."