In the Philippines people are hoping for jobs at home as well as abroad

- Published

Early morning in a bustling Manila street market. Election fever is in the air.

The main issues in this election are corruption, the economy, rising inequality and grinding poverty.

Almost a quarter of the country lives under the poverty line, despite posting solid growth of an average of 6% over the last few years.

Under President Aquino, the Philippines has shaken off its label of being the sick man of Asia, but the next president will have to continue with much needed economic reforms, fix the country's ailing infrastructure and create new jobs for young people.

Everyone I meet has a view on what Monday's election could and should bring.

Michael is a university graduate, and used to work as a human resources executive. But the pay was terrible so he quit and decided to join his mum selling vegetables in the market.

"I want a new president who can create better jobs for the youth," he tells me. "We don't have any opportunities here."

In the market I meet Maria Manuel, from the provinces.

She couldn't complete her university degree because her family couldn't afford it.

She's a domestic helper in Manila but is saving up to go and work in Japan as a care giver. She's even learning Japanese.

Her friends call her a "Filipina hero" because she is doing all of this to support her ten siblings back home.

"I knew from when I was seven years old that this was my responsibility as the eldest in the family," she told me. "I have no other choice. I have to go overseas to find work."

It's a story you'll hear over and over again in the Philippines.

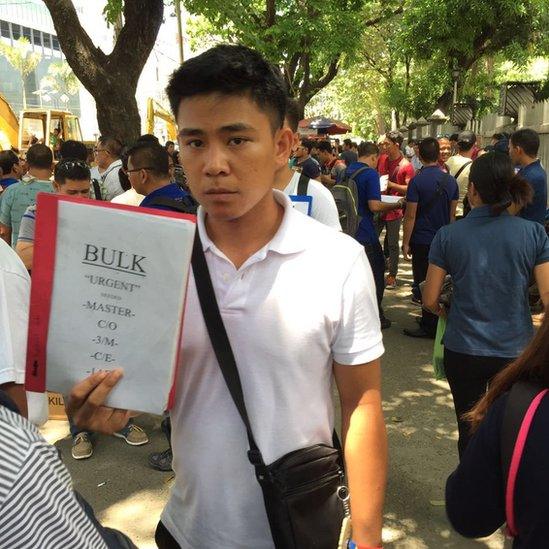

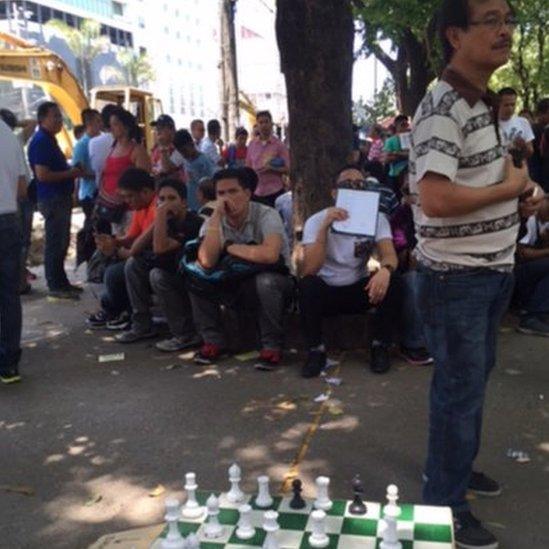

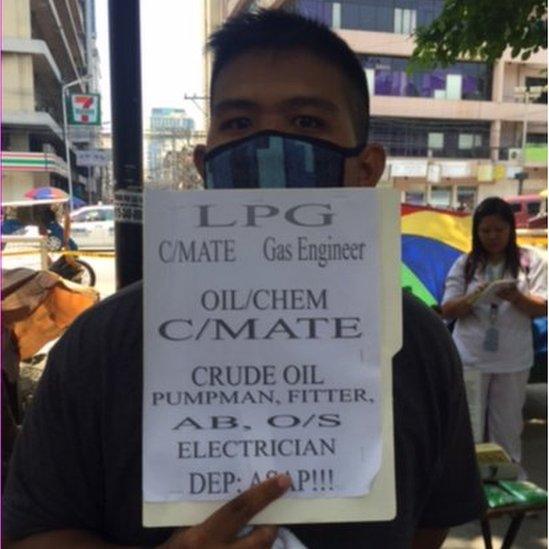

This is an informal job fair held on the streets of Manila. Agents come to find seamen and sailors to work on ships all over the world.

Hundreds of men, young and old, seek out shade from the searing hot sun, and wait to see if their qualifications are a match for the jobs on offer. If accepted, it means a stable and decent salary - but also years away from home, and their families.

Since the 1970s millions of Filipinos have gone overseas to work. It's thought that 10% of the population live and work overseas. They are major contributors to the economy - sending $25bn home in overseas remittances last year.

And it's not just the poor. It's an issue that cuts across all classes.

Even successful local business people have often had a stint overseas.

I met Levi Olidan, a hotel executive in Manila. She worked overseas for ten years, leaving her young family behind.

"At the time kids were very small," she told me. "It was good for us financially because I could give my children the best education but my marriage suffered. I hope the new president creates more decent jobs in the Philippines so parents can raise their kids here."

Levi tells me that generations of Filipino families have been torn apart because of the poor economy here. She also says that young people need to feel hopeful about the future to stay.

That's beginning to happen.

At a call centre across town I met Karen San Andres, a social media executive.

The call centre sector is creating millions of new jobs for tech savvy young Filipinos and this year is expected to match contributions to the economy from overseas remittances .

Karen tells me she never wanted to go overseas to work, because her dad left to find work abroad when she was born. She has only seen him a handful of times in her life.

"I never experienced the normal experience of having both a mum and dad," she tells me. "I always felt incomplete. And I don't want that for my future family."

Photographs: Charie Villa

- Published21 April 2016

- Published15 April 2016

- Published13 April 2016

- Published22 March 2016