The penny coin: Should we follow Ireland and phase it out?

- Published

You know that pot on your bedside table? Go and empty it, and you will find, on average, 173 penny coins.

The Royal Mint says there are 11.3bn of them "in circulation", but self-evidently most of them are not.

Sock drawers, ash trays and car glove-boxes are the recipients of coins that may never again be used for their minted purpose.

One reason is that a 1p coin is now worth less than the 1/2p was when it was abolished in 1984.

A penny back then was worth three times what it is today, thanks to the effect of inflation.

So should we rescue trouser pockets everywhere, by following the example of at least ten other western countries, and phase out the British penny?

'Better all round'

In parts of Europe it is already increasingly difficult to spend 1cent and 2c coins.

Several smaller countries now practise "rounding" to the nearest 5c, so that prices ending in a 1,2,6 or 7 get rounded down, with prices ending 3,4,8 or 9 rounded up.

Six European countries do this, including the Netherlands, Belgium and Finland.

The latest of these was the Irish Republic, which introduced cash rounding in October last year.

The central bank encourages retailers to take part in the scheme, external, although it is voluntary for both shops and customers.

Shoppers are made aware by stickers near the tills that say "Better all Round".

The smaller denominations can still be used in electronic transactions.

Inflation

However, Irish consumer groups have complained that retailers have used the opportunity to increase prices.

For example, some are said to have moved prices up from 97c to 98c, so they will get rounded up, rather than rounded down.

Dermott Jewell, policy adviser at the Consumers' Association of Ireland, says some shops are also rounding up automatically, instead of giving the customer a choice.

"As a result it's the consumer who needs to say, 'hang on, I only want to pay the quoted price'," he told the BBC.

The Central Bank of Ireland decreed that rounding should be applied to the total bill, rather than each individual item. It says that should curtail any inflationary effects.

But there have been instances of retailers rounding up individual items instead.

"The idea is not for shops to make a profit. Some stores are fleecing people," says Mr Jewell.

However the Consumers' Association still supports the principle of phasing out the smaller coins, which it says "cost ridiculous amounts".

Elsewhere Sweden, Denmark and Hungary have all introduced rounding in some form.

Australia, Canada and New Zealand have gone further, and phased out their smallest coins altogether.

Counting pennies

So what about the UK?

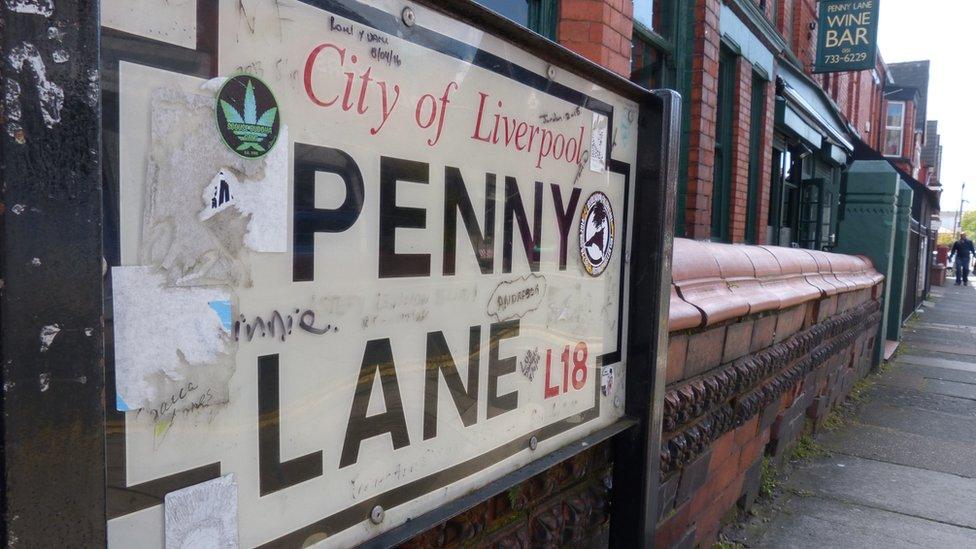

To canvas opinion, we went to a street that is better known for its Beatles, rather than its coinage, connection.

On the way there, the taxi driver was in little doubt.

"I think we should get rid of them," says Phil Mitchell. "I used to throw them out of the window. They're useless, aren't they?"

On Penny Lane itself, Debbie Davies, who owns a hairdressing salon, says she can't be bothered to count pennies, let alone take them to the bank.

"The only down side is that £1.99 sounds cheaper than £2.00. Customers might not like it, so businesses might not like it."

Debbie Davies says she can't be bothered to count penny coins

Further down is a firm of chartered accountants.

As a business that specialises in counting pennies, surely they would like to keep the coin.

But they are not keen.

"I don't think anyone would miss it," says John Paul McMullen, who incidentally denies being named after the Lennon-McCartney duo.

"I begrudge getting a penny. It goes into my car ash tray, until I go a penny over on petrol. Then it comes out."

Public Reaction

The Royal Mint won't reveal how much it costs to make a penny - nor how much we would save by stopping production.

But it does say that it costs less than 1p to produce each coin.

It still makes half a billion pennies a year, and claims they are popular with the public - an assertion which is in its own commercial interest, of course.

The Treasury - which is responsible for coinage policy - says there are no plans to withdraw the penny.

"Any decision to withdraw a denomination would need to be carefully considered, not only in terms of potential cost saving, but also in terms of public reaction and wider implications," a spokesperson told the BBC.

One of those wider implications would be the impact on inflation.

'British'

However, back on Penny Lane the public reaction looks rather different from what the Treasury may be anticipating.

Sharon Goldman, who runs the bakery, wants to keep the penny.

But her prices, which are already rounded up to the nearest 5 or 10p, suggest otherwise.

"That makes it easier for customers," she says.

Prices at the bakery are already rounded

At the Londis convenience store, many shoppers no longer wait to collect smaller coins.

"That guy there, he bought a 29p drink, but he didn't wait for his change," says manager Karen Rimmer. "The youngsters don't wait."

Yet young customer Amy Nelligan begged to differ.

"I love pennies. I just like to hold them. And there's something very British about them."

Like all of us, her attachment to the penny appears to be more sentimental than practical.

And that in itself may well underline the case for abolition.