Carney lights blue touch-paper on 'material' referendum risk

- Published

- comments

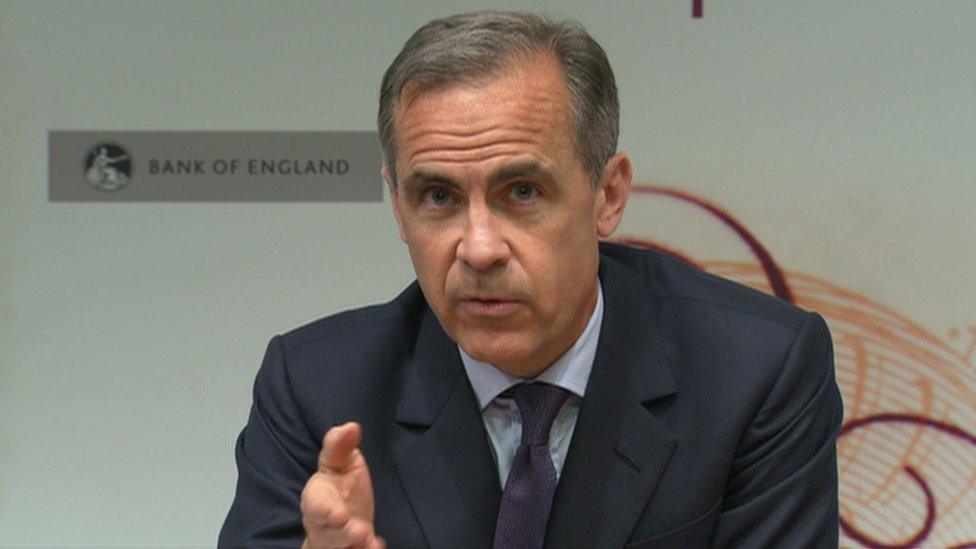

Giving evidence to the House of Lords economics committee last month, the governor of the Bank of England explained his approach to assessing the possible economic impact of the European Union referendum.

"Assessing and reporting risks does not mean becoming involved in politics," Mark Carney told peers.

"Rather, it would be political to suppress judgement."

The Bank has certainly not "suppressed judgement" in Thursday's major report.

In its assessment of the health of the UK economy one ringing sentence jumps out: "The most significant risks to the [economic] forecast concern the referendum," the Monetary Policy Committee says.

It goes on to reveal that far from this simply being a judgement on what Bank of England officials describe as the "uncertainty spike" around the fact the referendum is taking place at all - this is a judgement that Brexit would have a material effect on the economy.

'Action'

In a Bank world of carefully chosen words, "material" means significant. And significantly downwards.

"A vote to leave the EU could materially alter the outlook for [economic] output and inflation... [which] could lead to a materially lower path for growth and notably higher path for inflation," the MPC says.

Although the MPC, which is the Bank body that sets interest rates, announced it was keeping present rates at their historic low of 0.5%, it said it was ready to take "whatever action is needed" following the referendum.

In a letter to Mr Carney, released today, George Osborne said the Bank would face a "lose-lose" choice in the event of Britain leaving the European Union.

Either higher inflation, which would reduce household incomes, or higher interest rates, which would "impose costs on families".

Downgrade

The Treasury will certainly pounce on the Bank's assessment, which follows similar studies from the International Monetary Fund, the OECD and the London School of Economics.

In Thursday's report, the Bank downgraded second-quarter growth from 0.5% to 0.3%.

And some believe that the poor economic data of the last few days on manufacturing, construction and services (the mainstays of the UK economy) mean that growth in April could already be as low as 0.1%.

If that's the case, then "materially" lower growth would put the UK into negative territory.

And two quarters of negative growth mean one thing: Britain would be back in recession.

Concern

The Bank's economic experts did not stop at the phrase "materially alter".

The MPC went on to say that in the event of a leave vote, consumers could delay purchases leading to lower economic activity, firms could delay making investments in their businesses and unemployment could rise.

Sterling was also likely to depreciate further, "perhaps sharply".

As the referendum date has approached, the Bank and the Governor have become increasingly concerned - and increasingly vocal - about the economic impact of both the event itself (uncertainty risk) and one of the possible outcomes (Brexit).

And of course, there are a few that fundamentally disagree with him and the Bank's economists.

Margaret Thatcher's former economic adviser, Prof Patrick Minford, for example, says that leaving the EU would be a boost for the UK economy, freed, as he sees it, from the EU's "customs union".

Loud and clear

Mr Carney knows he may well face criticism today for becoming "too political" and accused of trying to influence how people vote.

His answer? It would be wrong for the Bank - responsible for financial stability - not to give its considered view, given the "shock" impact of a Brexit vote.

Yes, the Bank has lowered its growth forecasts for the next three years, and that is not all connected to the referendum.

Yes, there are other issues at play, like Britain's chronic productivity problem and slowing global growth.

But, if you want a clear exposition of where the Bank sits on the downside risks of Britain leaving the EU, today you have it. Loud and clear.