How 'robo recruiters' could affect your job prospects

- Published

Meet the new head of human resources...

Next time you apply for a job, it could be a computer algorithm deciding whether or not you fit the bill.

This is because clever, self-learning programs are getting better than human recruiters at analysing vast amounts of data gleaned from application forms, CVs (curricula vitae or resumes), and social media profiles.

Not only can they see if your credentials match the basic requirements of the job description, they can identify personality traits from the way you've expressed yourself on paper and online.

These algorithms try "to automate the 20-to-50 things the best recruiters do consciously or unconsciously" when shortlisting candidates, says Jon Bischke, chief executive of Entelo, external, a recruitment tech firm.

But he doesn't believe we'll ever reach the point where the computer makes the final decision.

"The goal is not to tell you who to hire," he says. "But it might tell you which five people to bring in to interview."

Learning on the job

The more data recruitment algorithms can analyse, the more accurate their assessments will become. And they can learn from previous successes and failures.

So if a selected candidate does well in the job, for example, his or her profile can be fed back into the algorithm so that it can spot people with similar profiles in future.

Gild believes self-learning algorithms make the needle in the haystack much easier to find

"Maybe in life I've looked at 20,000 or 30,000 resumes," says Sheerov Desai, chief executive of Gild, external, a machine learning recruitment firm. "A machine which has been fed hundreds of millions is going to outperform me."

Before the advent of powerful computers and data science, recruiters "would spend a lot of time doing manual research on applicants, Googling them, looking for details about work they've done in the past, seeing if they would be a good cultural fit," says Mr Desai.

All this has now been automated and speeded up.

Joining the dots

And these algorithms can often spot things we humans can't.

For example, one of Gild's clients complained that the agency was sending them Java engineers for a vacancy for an Android programmer.

"But the machine is scanning hundreds of millions of resumes, and it started to make the conclusion that Java and Android were quite similar technologies," says Mr Desai.

Gild's Sheerov Desai believes machines crunching millions of CVs will find better recruits

The machine was right - a Java programmer not already familiar with Android would pick it up very quickly, he says.

Another big advantage computers have over humans is that they are free from racial and gender prejudice.

Where human recruiters may - even unconsciously - dismiss candidates based on assumed ethnicity, sex or education, algorithms can assess anonymised applications objectively.

More features about the Future of Work

It is this kind of bias that drove Stephanie Lampkin to launch Blendoor, external, a "Tinder for jobs" that hides applicants' race, age, name, and gender and matches them with companies based on skills and education alone.

Happy staff?

Finding the best candidates is one thing, keeping them motivated and loyal once you've hired them is another.

Most companies set their goals annually, but research shows the average goal's shelf-life is actually just 40 days, says Kris Duggan, chief executive of BetterWorks, external, a business management software company.

Mr Duggan's product lets employees set goals quarterly and check in on their progress - he compares it to the fitness-goals system, FitBit.

BetterWorks is also researching how to apply machine-learning to assess how effective a company's goals really are.

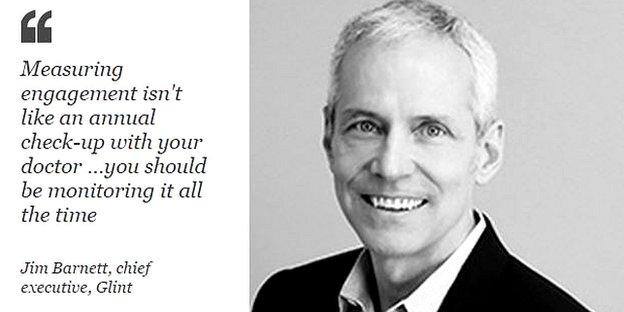

The more engaged staff are the better they perform, says Jim Barnett, chief executive of Glint, external, a company that regularly surveys employees.

These days, a more hi-tech approach to job-hunting is advisable

"Measuring engagement isn't like an annual check-up with your doctor - it's more like fitness and diet, which you should be monitoring all the time," he says.

Algorithms sift through the survey data to predict which teams may be running into problems, and suggest how managers might forestall them.

But how much monitoring is too much?

In a recent experiment at MIT, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, employees in a business wore monitors to track their basic emotional states.

Would monitoring anger levels help or hinder workplace relationships?

Algorithms sifting through the data identified that all employees experienced flashes of anger during their day. Further analysis showed this was always during meetings with a particular manager.

Now that might be useful to know if you're the boss, but how happy would staff be at that level of intrusion?

Not so smart

And what are the risks of relying so heavily on computers for recruitment purposes?

Algorithms trained to spot correlations and patterns - to seek out candidates that fit an ideal based on previous experience - may reject candidates from non-traditional backgrounds who would actually be excellent, some experts warn.

If you write the algorithm too rigidly, it may end up selecting competent applicants but reject "the next Picasso, Shakespeare, or Turing", says Petar Vujosevic, co-founder of GapJumpers, external, a recruitment tech company specialising in "blind audition" assessments of potential candidates.

Could algorithms miss the maverick geniuses in the pile of applications?

GapJumpers believes setting relevant online tasks for applicants is a better way of assessing talent than simply wading through - probably embellished - CVs.

"If people are not careful how they think about and build recruitment technology, in what is essentially a human process,"' says Mr Vujosevic, "it will only make people feel even less engaged and appreciated for their talents - and on a scale human recruiters never could manage."

Money talks

Caveats aside, the financial case for using self-learning algorithms is clear.

There are 5.3 million new job hires every month in the US, according to the country's Bureau of Labor Statistics. And each corporate vacancy attracts 250 applications on average.

That's a lot of documents for businesses to plough through. Automating this process saves money - that's the bottom line.

In the UK, replacing a departing staff member costs £30,614 on average, says Oxford Economics - which works out at more than £4bn a year in total for British business.

And with a third of new hires leaving after six months, as a business you really want to do everything you can to get the right person the first time round.

So if your job application is rejected in future, you may have to blame a computer, not the HR department.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter @matthew_wall, external