City shock at referendum result

- Published

A stocky, unshaven man in a blue raincoat strode across the concourse of Liverpool Street station at 5am, complaining bitterly to his taller companion. "Jesus. Jesus. It's bad. I'm heavily levered on this," he said, frantically rubbing his jaw.

The trader was typical of the tens of thousands of City staff who turned up for work this morning with their professional world turned upside down.

Encouraged by yesterday's opinion polls, which suggested Britain would stay in the European Union, professional investors bid up the pound and British shares. The pound finished the night of the vote worth $1.50, and the FTSE 100, an index that tracks the health of the UK's biggest listed companies, up 1.2%.

They were wrong. Britain voted narrowly to leave, and while most City traders slept - only a tiny minority stayed at their desks to watch the results - the pound was falling like a stone. Trading on Asian markets sent it down by nearly 10%, making it worth just $1.34. It was the biggest fall in the pound's history as a free-floating currency.

For some traders, it was the worst possible result - the trader's comment about being "levered" is a piece of City jargon meaning he had borrowed heavily to bet on the Remain camp winning.

The mood in the Square Mile was sombre - even shocked. Few could understand how they had called the result so wrong.

Nigel Wilson, the chief executive of Legal & General, the FTSE 100 insurer, told me there had been a "suspension of disbelief" - that because most in the City and the South East had wanted to stay in the union, they had assumed that would be the likely result.

Traders were left with the tricky decision of how to call the pound's performance over the day. Some predicted a rally - markets typically over-react to news of any kind - and were positioning themselves for the pound to strengthen. Others thought there would be more pressure on sterling, and were poised to sell.

As the 8am opening of the London Stock Exchange ticked closer, there was utter confusion. David Cameron was about to speak at No 10 Downing Street - surely he had to make his statement before the market opened?

Traders clustered round television screens waiting for the prime minister - but 8am came and went, and still no Cameron.

The exchange opened in ragged disorder; shares exposed to the British economy, like housebuilders and banks, immediately plunged by up to 30% - an unheard-of rout. Others, like gold miner Acacia, jumped as investors sought an obvious safe haven. The FTSE 100 sagged 7%, below the psychologically important 6,000 barrier, in the first half hour's trading.

Cameron finally emerged after about 10 minutes' frantic trading. The FTSE 100 started to rally, paring back some of its early losses, and sterling also recovered slightly. But it was clear there was going to be no sudden bounce - the mood remained one of stunned uncertainty.

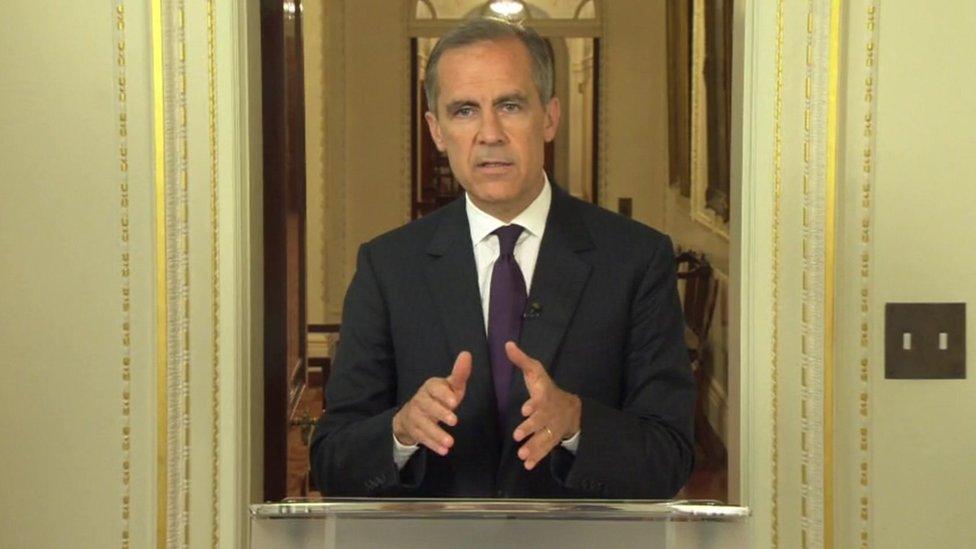

Nor could Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, who spoke after Cameron, do much to help the mood.

"This is not like the euro crisis," said Karen Olney, head of thematic equities at UBS. "Then Mario Draghi (the head of the European Central Bank) was able to stop the slide by saying he would do whatever what it would take. But there is no quick fix for this."

- Published24 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016