Brexit and the easing of austerity

- Published

- comments

It is sometimes easy in these incredible political times to forget that for most people "it's the economy, stupid" still holds true.

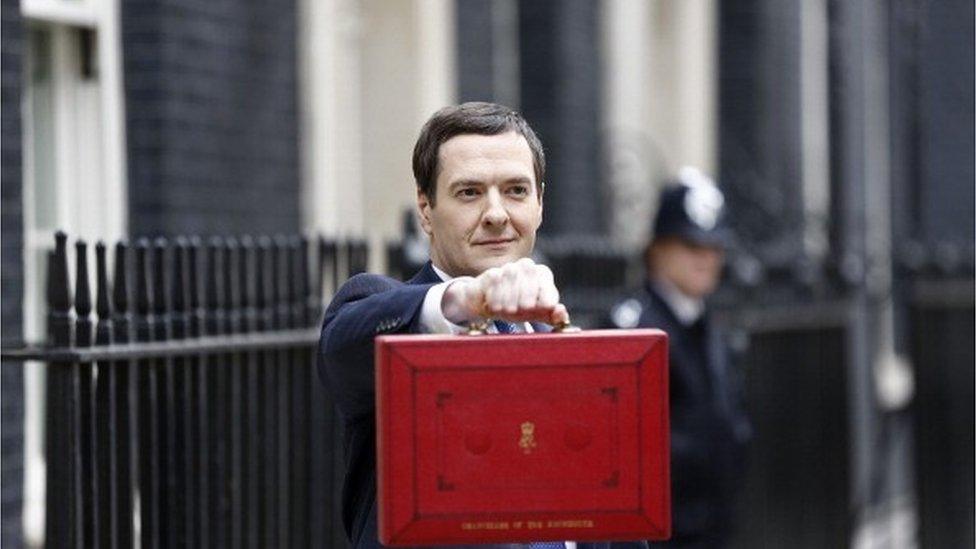

For the UK economy, one of the most important passages of Theresa May's speech yesterday was when she signalled that George Osborne's "fiscal rule" (to produce a budget surplus by 2020) was for the Treasury shredding machine.

"While it is absolutely vital that the government continues with its intention to reduce public spending and cut the budget deficit, we should no longer seek to reach a budget surplus by the end of the parliament," Mrs May said.

Now the chancellor has said he agrees, arguing that the government must be "realistic" about its fiscal targets and that austerity policies could be eased.

My Treasury sources point out that the "rule" can be varied in "non-normal" times.

And these are pretty "non-normal" times.

The abandonment of the fiscal target suggests the government could borrow more, presumably for investment in infrastructure and to mitigate the need for tax rises and spending cuts, if the economy does take a turn for the worse as some predict.

There are some interesting politics at work here as well.

Matt Hancock, the Cabinet Office minister, has backed Mrs May for the leadership.

He was formerly Mr Osborne's chief of staff and is about as close to the chancellor as it is possible to be.

Now Mr Osborne has backed Mrs May's fiscal position.

My sources insist the chancellor has made no decision on whom to back in the leadership election, if he comes out for anyone at all.

But Westminster's rune readers will only be leaning in one direction.

Mr Osborne's tone on the fiscal rule is sharply different from that struck by David Cameron on Wednesday.

When the prime minister was asked by Jeremy Corbyn to abandon the fiscal rule, the Prime Minister said it was not necessary and that the confidence of investors need to be maintained.

Well, with government borrowing costs falling as investors seek out "safe haven" assets in an uncertain world, that argument has withered.

The developing position of Mrs May and Mr Osborne is backed by many economists, with the Institute for Fiscal Studies saying that it was the "only" route available.

Some go further, arguing the whole austerity programme should be brought to a halt.

Gerard Lyons, the leading Brexit economist and former advisor to Boris Johnson, told me that with borrowing rates at record lows, the government should be taking on more debt and investing in infrastructure projects.

He said that the move would boost economic growth, which is predicted to fall below 1% by many economists because of the uncertainty of Brexit.

"I think austerity should end," he told me.

"If the austerity is not working the economy is weak and it's quite clear that there are large parts of the UK economy that would benefit from increased public spending.

"More importantly, the UK economy will actually benefit from increased infrastructure investment because the real lesson of the referendum is we're distancing ourselves from the weak growth region of the world economy.

"To actually grow strongly in the globalised economy the UK needs to invest, innovate and have more infrastructure."

I asked Mr Lyons if investors would baulk at a government taking on more debt?

"I worked in the financial markets for 27 years and spoke to investors across the globe," he said.

"A key part of this is how the story is told.

"Higher infrastructure spending justified against the backdrop of very low interest rates will produce stronger economic growth and the stronger growth in itself will help the future public finances.

"It's like an individual, if an individual goes out and borrows on the credit card, that's bad, if an individual goes out and borrows for their mortgage that's good."