Farnborough: A key role in Britain's aerospace industry

- Published

RAF Hawker Hart crews practising their formation flying for a 1930s air display

Farnborough: a small town in southern England; the birthplace of aviation in the UK and home for almost 70 years of arguably the world's most important air show.

It's an event that regularly sees a torrent of corporate deals, and has played a key role as a marketplace for Britain's aerospace and defence firms.

It is a showcase for a sector worth £55bn a year, the fifth-largest industry in the UK that employs 340,000 people.

Indeed, the last show in 2014 saw a record $204bn (£157bn) worth of orders being placed.

"Farnborough is a global shop window for the UK and Europe, for the entire world," Shaun Omerod, chief executive of Farnborough International, said ahead of this year's show, which starts on Monday.

"It connects UK small and medium-sized companies - who ordinarily wouldn't get this access - to the global market."

Displays like this, by a US F-22 Raptor fighter back in 2008....

...are guaranteed to get cameras clicking. This year the F-35 will take centre-stage

If Farnborough's own connection with flying starts in 1904 with the Army Balloon Factory and the first flight of an aeroplane in the UK (by the showman Samuel Cody in 1908), then the history of today's air show actually begins in suburban London.

In a bid to sell their wares the Society of British Aircraft Constructors (SBAC) organised a one-day exhibition at the annual RAF flying display at Hendon in 1932.

The air pageants at Hendon led to today's international show at Farnborough

It was small by today's standards, with just 35 aircraft on display and only 16 companies taking part; this year there will be some 1,500 exhibitors.

After the Second World War the event was initially held at Radlett, moving in 1948 to Farnborough, the home of the Royal Aircraft Establishment - responsible for researching and testing experimental designs.

Airliners on display at the first show held at Farnborough in 1948

The show has been the stage for many of the high points of post-war aviation, from the wonderful to the whimsical, such as the Saunders Roe A1 flying boat jet fighter.

First flown in 1947 at the show it was an heroic but ultimately flawed attempt to marry a long-range fighter with a flying boat.

The idea was it wouldn't need to land on aircraft carriers as the Allies fought Japan across the Pacific Ocean, but the end of the war put paid to any use it might have had.

Is it a bird, is it a plane? The Saunders Roe jet flying boat fighter came too late to see service

The 1949 show saw the truly massive Bristol Brabazon, then the world's biggest airliner. It was designed to conquer the transatlantic air routes for Britain's aircraft industry.

Driven by eight propellers it was so big that its construction was delayed while the runway at Bristol's Filton factory was extended so it could take off. Yet despite its size it only carried 100 passengers, and airlines thought it too big and expensive. Only one was ever built.

The Bristol Brabazon, an airliner so big they had to build a new runway for it

The same event also saw the UK introduce the world's first jet airliner - the DH Comet.

The Comet's pressurised cabin meant people could travel in comfort. It was a commercial success at first, yet the design hid a serious weakness.

Its square window frames contributed to metal fatigue, which led to a series of fatal crashes within a couple of years. The entire fleet was grounded for four years while the flaws were ironed out and the aircraft strengthened.

The Comet was the world's first jet airliner but the airlines bought its American rivals instead

Later Comet models flew well - indeed the RAF used the Nimrod, a version of the Comet, until 2011 - but they were not as cost-effective as their American competitors. Many airlines switched to buying Boeing's new 707 and Douglas's DC8 passenger aircraft instead.

1952 was marked by the worst ever accident at a UK air show. A prototype de Havilland DH110 broke up in mid-air, killing the two crew and 29 spectators.

The tragedy led to changes in safety rules at such shows.

Aerobatics have always been a key part of the show, whether with the 1950s Black Arrows...

...or today's Red Arrows

If the commercial crown was gradually passing to the US in the mid-1950s, spectators could still expect to be entertained by a host of British hardware.

It was a time of experimentation and exploration.

Jet fighters and drones: Some of the UK's key combat aircraft

Witness the delta-wing Gloster Javelin; the Fairey Rotodyne, a helicopter with jets on its rotor-blades; the Fairey Delta, the first plane to fly faster than 1,000mph; and the jet and rocket-powered SR53 fighter.

1953 saw Britain's nuclear triumvirate, the Valiant, Vulcan and Victor V-Bombers, at the show for the first time - alongside a scarlet painted Hawker Hunter jet fighter that Neville Duke had flown to regain the world speed record for the UK.

The Vulcan, along with the Valiant and Victor, made up Britain's nuclear-capable V-Bombers

Vertical takeoff and landing was one of the next milestones, with 1962 seeing two Hawker Siddeley P1127 prototype vertical/short takeoff and landing (V/STOL) aircraft at the event.

The aircraft would later become the Harrier, which is still in service with the US Marine Corps.

Hawker Siddeley's prototype "jump jet" was a resounding success...

...but the revolutionary TSR-2 was controversially scrapped before it could enter service

Perhaps the greatest aircraft never to make Farnborough was the revolutionary TSR-2, which first flew just after 1964's show in September that year - and was controversially cancelled by a Labour government just a few months later because of rising costs.

As aircraft designer Sir Sydney Camm famously said: "All modern aircraft have four dimensions: span, length, height and politics; TSR-2 simply got the first three right."

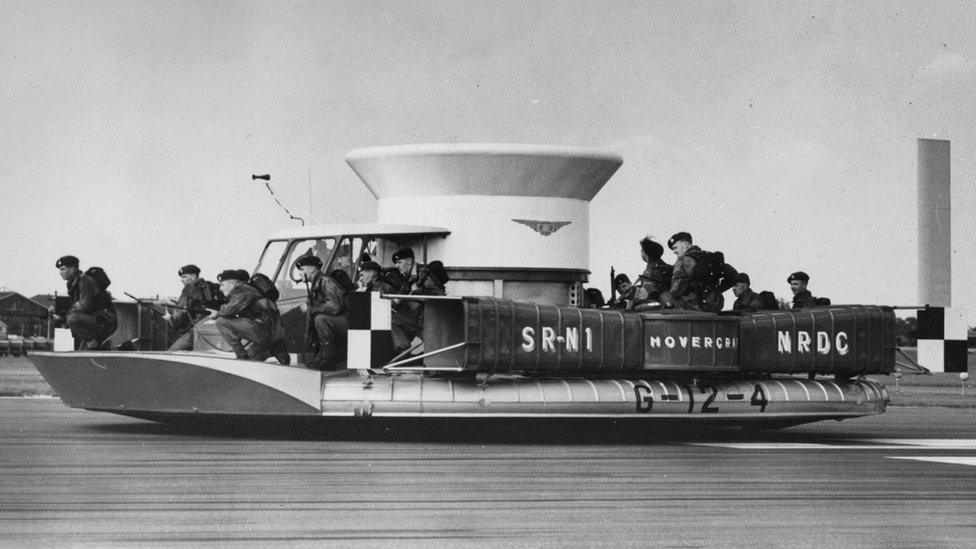

Prize for the lowest "flying" craft at the show goes to the SRN1 hovercraft - complete with Royal Marines

By the 1960s things were changing. The show itself became biennial in 1962, taking turns with Paris. And the rapidly escalating cost of aircraft development and increasing international competition led to consolidation in the UK's own aerospace sector.

With the merger of once proud rivals, just two big aircraft manufacturers remained - British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) and Hawker Siddeley. In 1977 these would join Scottish Aviation to form British Aerospace, now BAE Systems.

Farnborough was becoming more international, allowing in foreign aeroplanes so long as they had a British engine or components in 1966, and then by 1974 fully opening the doors to international aircraft.

A visitor looks at a Rolls Royce Trent jet engine, used on the Airbus A380

A Swedish Gripen fighter puts on an aerial display during 2004's show

1974 saw US firm Lockheed bring the biggest and the fastest aircraft to the show: the C5 Galaxy military transport plane and the high-flying SR-71 spy plane.

Britain's own Concorde made its first appearance at the show in 1970, and then at subsequent shows that decade; it was a brilliant technical Franco-British achievement, but one which failed to win orders from the world's airlines.

Check out some of the most significant UK-built airliners of the past 70 years

The Cold War may have reached a new intensity in the 1980s, but the decade also saw the first appearance of Soviet combat aircraft in the West, with two Mig-29 fighters at Farnborough in 1986 as well as the gigantic Antonov An-225 transporter.

Another memorable show for aerobatics fans came in 1990, when two Soviet SU-27 fighters performed the "cobra" manoeuvre.

This involves raising the noses of the aircraft to beyond the vertical position before dropping it back to normal flight, emulating the strike of the snake.

A Sukhoi SU-27 demonstrates the "cobra" - the aircraft's nose is vertical, but it's still moving forward

Half-helicopter, half-conventional aeroplane: the tilt-rotor Bell/Boeing V22 Osprey

In recent years Farnborough has become a key marketing battleground for the world's two largest passenger aircraft manufacturers, Airbus and Boeing, allowing them to display their latest offerings and to announce new orders.

Airbus showed off its A380 double-decker airliner in 2006, an aircraft designed for mass market long-haul routes; while 2010 saw Boeing's 787 Dreamliner, promoted as the world's most fuel-efficient airliner.

Airbus's A380 has been a popular sight at recent shows...

...as has Boeing's 787 Dreamliner

So where now for Farnborough as it approaches its own 70th anniversary in 2018? Brexit may have clouded the immediate future, but many are robustly confident of their ability to ride out the changes.

"We may not be the manufacturing guru that existed in the days of the empire," says Phil Seymour of leading independent aviation consultancy IBA.

"But we still produce significant parts for aircraft - we have a huge service sector - and London remains the foremost centre of aviation finance and insurance. So the event attracts many thousands of people."

Richard Branson came to showcase a replica of Virgin Galactic in 2012, planned as the world's first commercial space liner

Drones are now a major attraction for many visitors, with increasing numbers of civilian and military UAVs on display

"Farnborough is one of the very few international trade events which is left on UK soil," says the show's chief executive Shaun Omerod.

"Many of the traditional ones have disappeared or moved to mainland Europe over the years.

"It truly is a jewel in the crown."

Follow Tim Bowler on Twitter@timbowlerbbc, external