Would free university tuition work in the US?

- Published

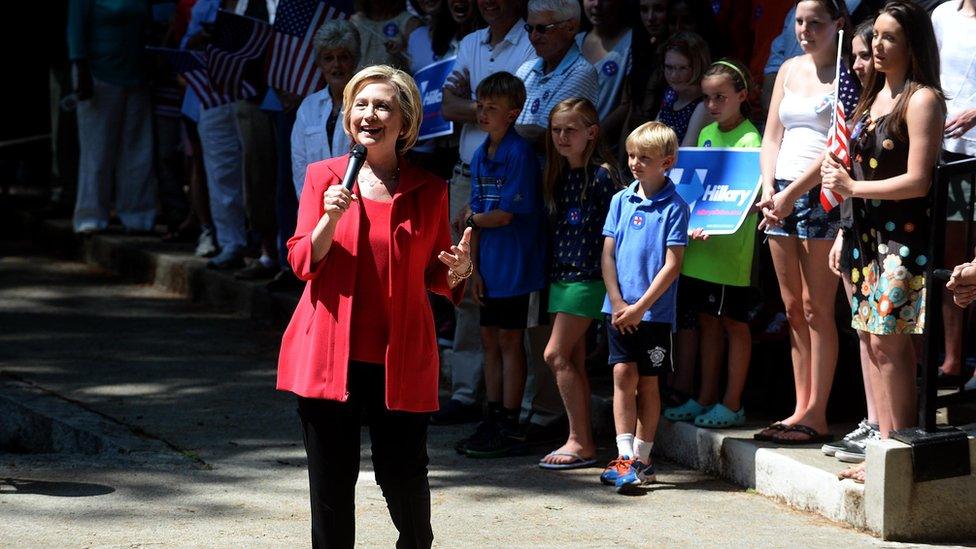

Under Hillary Clinton's plan, schools like the University of Colorado would be free to many students

Hillary Clinton has adopted Bernie Sanders-style policies that would appeal to his followers, including free public tuition to state universities. But does her plan make the grade?

Last week, Mrs Clinton announced a new plan to make university free for some students.

Under the former secretary of state's plan, students from families that earn less than $85,000 (£65,600) a year would be eligible for education free of tuition fees at public universities in their state. The level of income required for eligibility would increase by $10,000 a year until it reaches $125,000 by 2021, external.

Students would be asked to work 10 hours a week to pay for cost-of-living expenses.

Universities would be asked to improve their value by controlling costs and improving graduation rates.

The plan also looks to cut the amount of existing and future debt for students attending private or out-of-state universities.

Hillary Clinton's proposal would make university free for millions of students from low- and middle-income families

Currently, there's close to a trillion dollars in student loan debt in the US.

In places like Scotland, Norway and Germany, free university is already a reality.

Clinton's plan is an expansion on her earlier proposal to increase the amount federal student grants and make refinancing student loans easier. Her campaign estimated the original proposal would cost $350bn at the federal level. States would have to cover the rest - likely tens of billions of dollars.

This expanded plan will cost even more, but the campaign has not said how much.

Bernie Sander's plan to make university free was criticised for its cost, approximately $750bn.

More taxes, less tuition

At the federal level, Secretary Clinton believes this money would come from closing tax code loopholes and limiting tax deductions for high-income taxpayers.

Bernie Sanders introduced the idea of free university tuition in the 2016 election

Other countries use taxes to fund free university education but have far fewer students than the US, external. In 2013 Germany had 2.7 million students in higher education and Norway had 255,000.

The US had 20 million students, external in higher education that year.

More local funding

Under Mrs Clinton's plan, states would be required to make some contribution for their universities to receive federal funding. Mr Sanders' plan also took this approach.

Most federal programmes, like the public health insurance programme Medicare, work this way.

But under the current public university funding model, states are not required to give any minimum amount of financing.

The way states give universities funding is also different from how money from the federal government is provided.

Most state financing is given as general-purpose funding for the university, while most federal money is allocated to individual students, usually in the form of a grant.

Close to $1tn in outstanding student debt is weighing on the US economy

According to Barmak Nassirian, director of policy analysis at the American Association of State Colleges and Universities, this has contributed to the rising cost of universities in the US.

Because they knew students could get federal vouchers - either grants or loans - and with mounting pressure on their budgets, states reduced their contributions to universities. Nationally states have reduced per-student spending by 25% over the last 25 years.

"The creation of these vouchers in a perverse and unintentional way created a path of least resistance for the state to back off," says Mr Nassirian.

The reduction in state funding was most pronounced following the recession.

Before 2010 states provided 65% more funding than the federal government to public universities. Since the recession, the amount of federal aid has increased while state funding has slipped - mostly due to losses in tax revenue.

Local politicians across the country, including those in the New York state capital, could be forced to reshuffle budgets to find more funding for universities

"States are still climbing out of a slow recovery from the great recession," says John Hicks, executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers.

According to Mr Hicks, states are struggling to meet the financial needs of local primary and secondary education as well as pension and healthcare programmes.

"If states could put more money into higher education today, they already would," he says.

There's one more catch to the plan - free university tuition doesn't mean more people will be able to get a degree.

Norway is the only country that both offers free university and has a larger proportion of educated people than the US.

In 2013 the share of 25- to 35-year-olds with a university degree was 45% in America compared with 47% in Norway. In countries with the highest university attendance - Canada, at 58% and South Korea at 63% - students pay tuition similar to the cost of attending a public university in the US.

Over the past 25 years states have cut a quarter of per-student spending

With a plan like Mrs Clinton's, the demand for in-state public education would rise, but limits on government budgets could lead to cuts in the number of accepted students.

"There isn't unlimited capacity in the public sector," says Mr Nassirian. "The capacity issue is a very serious one. The assumption has to be that the demand for public institutions would expand if they were free or significantly more affordable than they are today."

So, if Mrs Clinton wins the election and her plan goes through, a lot of Americans - university degree or not - might be in for an economics lesson in supply and demand

- Published11 February 2015

- Published9 March 2016