Social division stays in online learning

- Published

The debate about access to computers should move to how they are used, says OECD research

There are strong social divisions in how young people use digital technology, according to international research from the OECD.

The economics think tank found that in many countries wealthy and poor pupils spent similar amounts of time online.

But richer youngsters were much more likely to use the internet for learning rather than games.

The study argues that even with equal access to technology a "digital divide" persists in how the internet is used.

The OECD report, based on data from more than 40 countries mostly in Europe, Asia and South America, looked at how teenagers used online technology at home.

Access to the internet and digital technology are seen as important to educational achievement.

Young Finns are most likely to use the internet for information

But this study shows significant differences in how teenagers spend their time online - and suggests that new technology does not stop old social divisions.

It also suggests that encouraging strong reading skills is the key to making the most of the internet.

The researchers found online activity was directly linked to "socio-economic status", with wealthier students more likely to use the internet for educationally advantageous activities such as gathering information and reading news.

Where young people are most likely to use the internet for information

Finland

Iceland

Estonia

Norway

Slovenia

Denmark

Czech Republic

Latvia

Israel

Liechtenstein

Poorer students were more likely to use the internet for games or chatting online.

The information was gathered as part of the international Pisa tests and it shows how teenagers might be using the internet to help their studies.

Would the time spent on computers be better spent on traditional lessons in literacy?

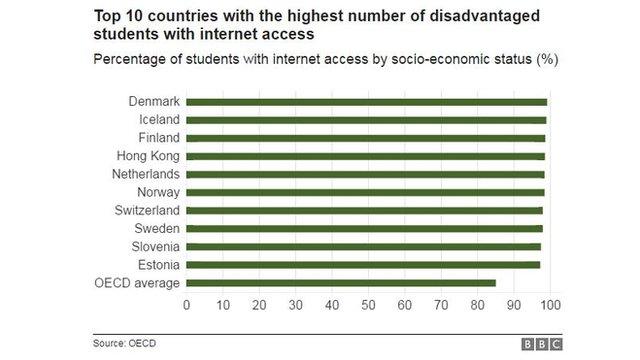

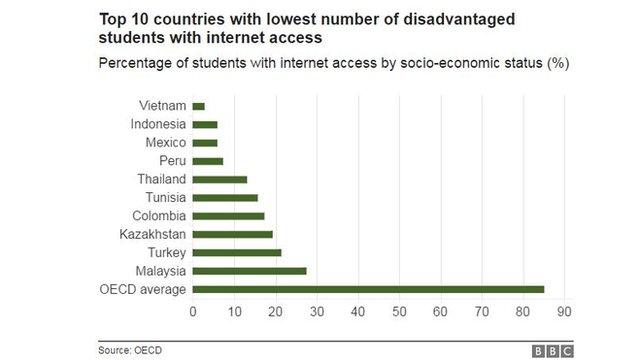

The research suggests that inequality emerges, even in countries with near-universal internet access.

"Equal access does not imply equal opportunities," says the report, and a lack of familiarity with using the internet for information will have a negative impact in areas such as studying or looking for jobs.

More stories from the BBC's Global education series, external looking at education from an international perspective and how to get in touch

This happens within countries, but the study also reveals big differences between countries - with teenagers in wealthier northern European countries more likely to use the internet for getting information, rather than playing or socialising.

Finland and Iceland have the highest levels of teenagers using the internet for information, followed by Estonia, Norway and Slovenia.

There were also higher-than-average educational uses of the internet in Denmark, Hong Kong, Poland, Germany and Singapore.

In Mexico, Jordan and Turkey young people were much more likely to go online to play games and much less for news or information.

Those spending the longest time online were also from Nordic countries, Denmark, Sweden and Norway. And in a number of more affluent European countries, including Belgium, Finland, Denmark and Germany, poorer families spent longer online than wealthy ones.

The UK did not take part in the section of the survey comparing types of computer use, but it did provide data for overall internet access.

This showed very high levels of online access in the UK for both rich and poor.

The study says that new technology has not changed old social divisions

It was among a group of countries including the Nordic nations, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Hong Kong, where the wealthiest and poorest quarter of the young population almost all had the internet at home.

This was in contrast to countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, Mexico and Peru where poorer families were much less likely to have internet access.

In such countries, the report says school plays a much more important role in ensuring that young people have access to information and communications equipment.

Longest time spent online at home

Denmark

Sweden

Norway

Macau

Hong Kong

Iceland

Taiwan

Estonia

Netherlands

Australia

The report says that there have been efforts to narrow such gaps in access, but a more valuable response might be to focus on making sure that all young people have strong literacy skills.

"Ensuring that every child attains a baseline level of proficiency in reading will do more to create equal opportunities in a digital world than will expanding or subsidising access to high-tech devices and services."

Parents might want to encourage computer skills to give children a head start

But the findings were criticised as "simplistic" by Mark Chambers, chief executive of Naace, the UK body supporting the use of computers in schools.

He rejected the idea that it should be a choice between either improving reading or focusing on digital skills, as both were mutually beneficial.

Mr Chambers said it was no surprise that the wealthy would have the most confidence and take the most advantage of new technology.

And he questioned whether internet access at home was really the same for rich and poor, suggesting that it did not mean that all young people had equal access to broadband and their own computer.

"In the UK, homes of students from a low economic, social and cultural background often don't have landline phones and internet access through them, relying instead on mobiles," he said.

Schools should work to reduce social divisions, he said, rather than "retrenching to Victorian approaches".