'High price' for the lost savings habit

- Published

Young families are leaving themselves in a financially fragile state, academics say, amid reports that people are losing the savings habit.

Failure to put money aside exposed them to expensive debts, according to John Ashton, a professor in banking.

A quarter of UK households would turn to credit or ask family and friends for help when faced with an unexpected bill, recent surveys suggest.

Yet low interest rates are undermining any incentive to save.

"We are asking young people to save in an environment where there are no Brownie points for saving," said Janette Rutterford, professor of financial management at The Open University Business School.

Ways to save

The BBC News website asked members of the UK Money Bloggers community, external for their tips about saving for a rainy day fund.

"Every time you check your balance online, transfer the odd pence amount to a savings account. Little and often will add up quickly." Cass Bailey, The Diary of a Frugal Family, external

"Put cash into one of those money tins that don't open without a can opener." Kalpana Fitzpatrick, MummyMoneyMatters, external

"You can save over £650 in a year by saving just 1p a day and increasing the amount by a penny for the rest of the year. So, on day one you save 1p, day two is 2p, day 127 would be £1.27 and the last day is £3.65." Naomi Willis, Skint Dad, external

"Forget Isas, instead stack high-interest current and regular saving accounts, feeding money from one to the next, to earn a huge 5% or 6% in interest on a decent chunk of money." Andy Webb, Be Clever With Your Cash, external

"Automate your savings every payday into an account that is awkward for you to access - my savings go into a bank that doesn't have many branches here, so it is difficult for me to go and take any money out if temptation strikes." Francesca Mason, From Pennies to Pounds, external

Two surveys have revealed the extent to which families have lost the savings habit to cover the cost of unplanned events, such as fixing the car or paying for repairs in the home.

The independent Money Advice Service, as part of its Financial Capability Survey, asked 3,500 people across the UK how they would pay for an unexpected bill of up to £300 within a week.

Although 22% of them would dip into their savings (and 43% could pay with day-to-day cash), some 24% would use high-cost credit, ask for family help, or face problems.

Breaking this down reveals:

6% of all respondents would use a credit card, loan or overdraft

6% would take a loan from family or friends

6% did not know how they would pay

5% would not be able to pay

1% would go overdrawn without authorisation

Prof Ashton, of Bangor University, described this group as "financially fragile". He said the use of overdrafts and other loans was a much more expensive way to pay bills, and ultimately meant debts could spiral and homes could be at risk.

"This low level of precautionary savings is a big concern for policymakers," he said.

Squeeze tightens

The lack of savings becomes more acute were the cost of the unexpected bill to rise to £500, a smaller YouGov survey for The Times newspaper, external suggested.

Nearly half (46%) of manual workers and the unemployed would not be able to afford paying for an unexpected bill of this kind, it said. Nearly a third (31%) of typically middle-class professional, junior managerial and administrative workers would also be unable to pay.

Young adults aged between 18 and 24 were the age group least likely to have funds available, the survey also suggested. Women were less likely to have cash available than men, and people in the Midlands, Scotland and Wales were the hardest-pressed in the UK.

The typical UK household is hardly any better off now than it was before the financial crisis.

Median average household disposable income in the UK was estimated to be £25,700 in 2014-15, the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show. Before the economic downturn, the average was £25,400.

Any money that is spare, and which could be saved, is - in many cases - failing to be diverted into emergency fund savings for a number of reasons, according to Prof Ashton and Prof Rutterford.

Firstly, there is no longer a savings culture in the UK that mirrors a thrifty society such as China.

"There is easy access to credit. Customers do not engage with their bank, nor talk to their bank manager. Decisions [on buying items] are made much more quickly, and people do not understand compound interest," said Prof Rutterford.

Lack of interest

Secondly, confidence in the safety of savings took a hit during the financial crisis.

Thirdly, and most importantly, interest rates have been pitiful for more than seven years.

Even amid the low interest rate environment, Prof Ashton's research shows that loyal savers have received an even worse return on their savings than new customers.

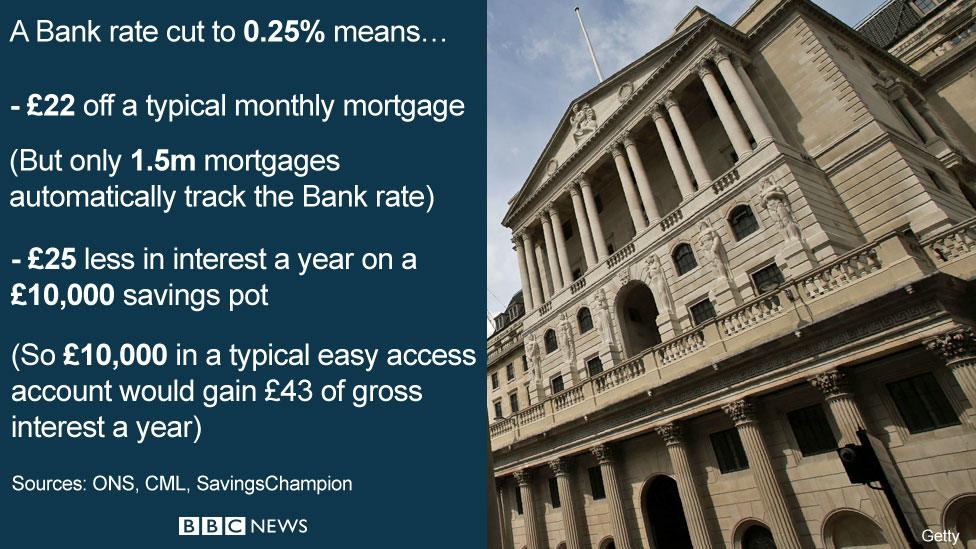

The Bank of England has signalled that the base rate, or Bank rate, may fall. Although this did not happen in July, as was widely expected, it may still do so in August. That can only make matters worse for those trying to put money aside who will see it gain little in value.

"Savers really have been the sacrificial lambs of this downturn. While borrowers have benefited from historically low rates, savers have never known it so bad," said Anna Bowes, founder of independent advice site SavingsChampion.

Getting into a savings habit was important but, after that, the only possible tactic for savers trying to get more for their money was to move that money around by switching accounts, she said.

"With almost a third of easy access accounts currently paying 0.25% or less, savers need to act now to improve their returns, because better rates are available. By leaving money languishing in these poor accounts they are playing directly into the providers' hands," she said.

Small print

"The actual act of putting money aside regularly is more important initially than the actual interest earned, but once the amount increases, a better interest rate can really make a difference."

Some of the better-paying accounts have various terms and conditions, such as a requirement for regular deposits and limited withdrawals. After a certain period of time, a switch would be needed, she said.

All of this requires customers to be active.

They would also need to make the act of putting money aside a monthly task in itself, rather than simply regarding their money-saving efforts as putting a lid on discretionary spending or searching for money-off deals.