Testing times for Europe's banks

- Published

European banks are being tested to see how they would stand up to future financial shocks

The results of European bank "stress tests" have been announced, with the aim of establishing how well the banks could cope with a new financial shock.

Banks have done them on their own account for many years.

But this type of exercise has been adopted by official regulators in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008.

What has been tested?

In short, the resilience of the banks. Some 51 European Union banks were tested covering 70% of the sector. The exercise covered the eurozone and the rest of the EU - including the UK.

Regulators have looked at how well banks would stand up under two scenarios up to the end of 2018.

There's a "baseline scenario" that assumes continued - though unspectacular - economic growth, in line with most mainstream forecasts. Then there's an adverse one that involves a recession and would lead to more problem loans, and lower profits or losses.

Unlike previous stress tests there is no threshold for pass or fail

The key question being asked is how would banks' financial foundations - their capital - hold up?

How much would they have left under these scenarios and how would that compare with the amount they are required to have under banking rules?

A stress test looks at how much a bank might lose and whether it would still have a decent amount of capital to keep trading and take any losses that it might be hit by in the future.

What is bank capital?

Capital is a financial measure of a bank's strength, its ability to withstand losses.

It is the value of a bank's assets minus its liabilities or debts. A bank's assets include cash, loans and securities, while its liabilities cover customer deposits, and money it owes to other banks and bondholders.

So where does it come from? Two key sources are the money put in by shareholders and profits the bank makes and does not hand out to the shareholders as dividends (known as retained profits).

2008's financial crisis was partly due to European banks not having enough capital to cope with losses on problem loans

If a bank has a bad year and loses money the amount of capital falls. Shareholders typically see the value of their holding fall, but the bank should still be able pay its debts.

If that process goes too far, however, the capital can be wiped out and if the bank can't pay its debts then it's insolvent - bust.

The international financial crisis was in part the result of banks not having enough capital to cope with losses on problem loans and complicated financial securities.

Overall the ECB appears relatively comfortable with the amount of capital held by eurozone's banks

The bailouts consisted partly of governments providing additional capital which gave taxpayers a shareholding. (Some of this has been repaid or the shares sold off by the government concerned).

One of the main aims of reforms to bank regulation since the crisis has been to ensure that they are not caught with insufficient capital in future.

What are the stress test scenarios?

The key one is the adverse scenario, external. An ECB official described this hypothetical scenario as a "severe economic downturn".

Under this scenario, the eurozone economies, the EU and the UK all contract in 2016 and 2017 - only resuming growth, though not very strongly, in 2018.

All of them end up nearly 7% smaller than they would have been in the baseline scenario.

The weakness is assumed to be the result of setbacks to the domestic economy, to foreign economies and to the financial system in the shape of higher interest rates, lower share prices and lower property prices.

Higher rates and lower asset prices increase the risk of loans not being paid and of there being inadequate security to sell and cover losses if the borrower does default.

The stress tests look at how these shocks would affect the values of banks' assets, their profitability and the amount of capital they would end up holding.

Who does the tests?

The banks themselves make the initial assessments of how they would be affected in the stress test scenarios. Their results are challenged by the supervisors. In the UK that means the Bank of England, and for the large banks in the eurozone, the European Central Bank.

The exercise is co-ordinated by the European Banking Authority.

Is there a pass/fail threshold?

Unlike previous stress tests there is no pass/fail threshold for the level of capital. But the estimates for how much any bank would have under the various scenarios will feed into the regular assessments made by supervisors.

A bank that comes out of a stress test really badly could ultimately have to be bailed out or bailed in - this latter is a process in which creditors have to take losses to keep the bank afloat.

Italy's third largest bank, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, is trying to raise new capital as part of plans to fix its balance sheet

The tests could eventually lead to some banks having to raise more capital, or face restrictions on the amount of profits they can distribute to their shareholders - because if profits are not distributed they boost a bank's capital.

Any particular problem areas?

Overall the ECB appears relatively comfortable with the amount of capital held by eurozone's banks.

"The ECB perceives the current level of capital in the euro area banks to be satisfactory and intends to keep the supervisory capital demand stable," says Korbinian Ibel, a senior ECB official.

"As the banks went into this stress test with a higher average capital ratio than in earlier years and are overall more resilient, the stress test results are not expected to lead to an increase of the overall level of capital demand in the system."

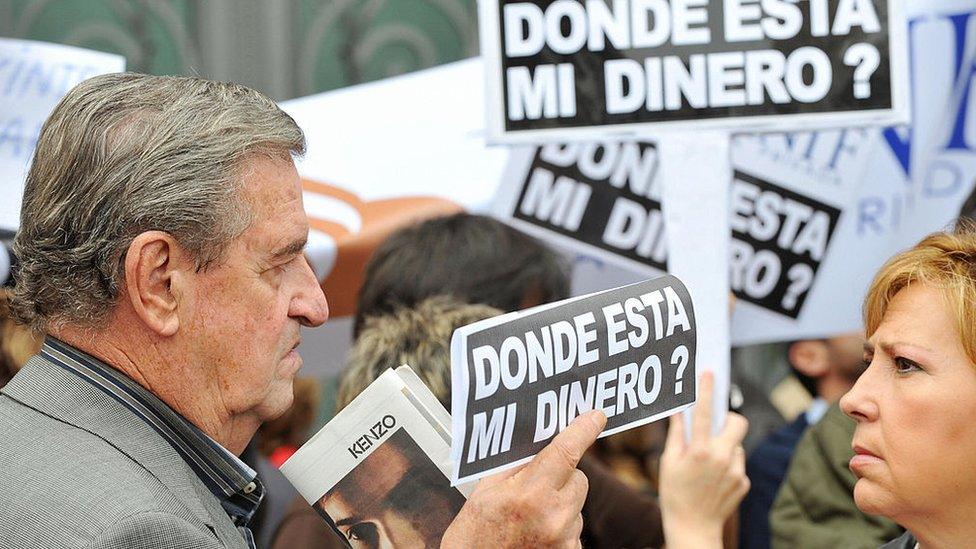

But there have been concerns in recent months about the problem loans weighing down some Italian and Portuguese banks.

Deutsche Bank, Germany's biggest, is seen by the International Monetary Fund, external as a potential risk to international financial stability and its share price is low compared to the value of the bank's assets and liabilities.

That said, it is not in immediate danger, though its US operation, along with that of the Spanish bank Santander, did fail stress tests conducted by the US Federal Reserve earlier this year.

- Published21 July 2016

- Published5 December 2016

- Published6 July 2016

- Published30 June 2016