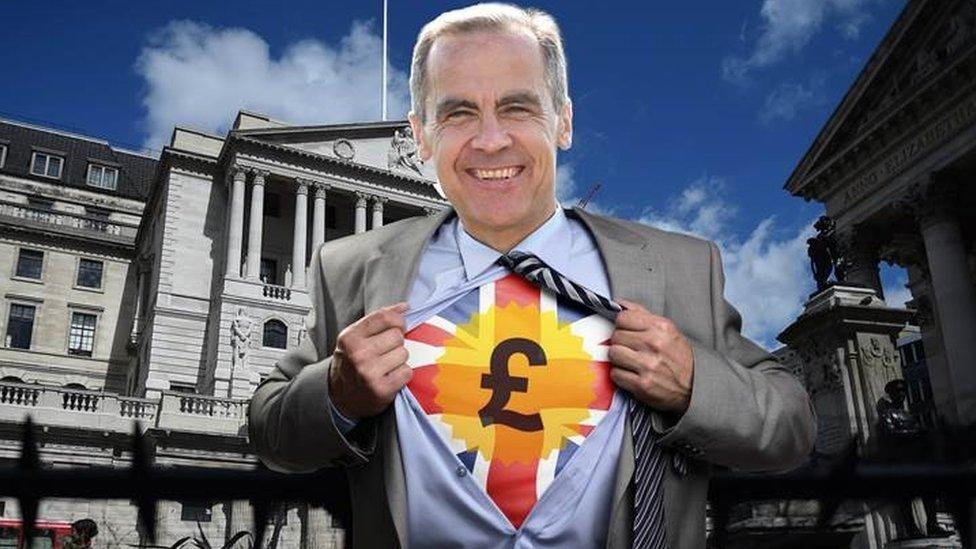

Carney rips his shirt off

- Published

- comments

The Bank of England is not very confident about the future of the economy.

It says growth will fall dramatically, announcing the biggest downgrade to its growth forecast since it started inflation reports in 1993.

The economy, it says, will be 2.5% smaller in three years' time than it believed it would be when the Bank last opined on these matters in May.

Unemployment will rise (although only marginally), inflation will rise, real income growth will slow and house prices will decline.

Growth, the Bank believes, will fall perilously close to zero over the final six months of this year.

Although, possibly because of the significant actions the Bank is taking today, the UK will avoid a recession.

And, as the government points out, the UK economy is entering the next 12, crucial, months in relatively strong shape.

More cuts?

With economic uncertainty ahead, the Bank has rummaged around in its monetary cupboard and discovered several kitchen sinks to throw at the issue.

Interest rates will be cut, and the Bank says it expects - if economic growth is as weak as expected - further rate cuts.

That could mean rates as low 0.1% next year, it suggested.

Quantitative easing - the buying of government and business debt - will be increased by £70bn, reducing government and business borrowing costs and, the Bank hopes, increasing the stock of available lending.

There will also be a new scheme - called the Term Funding Scheme - which will provide extra finance to banks to encourage them to pass on the cut in interest rates to businesses and consumers.

Together with enhanced QE, this scheme could see the total support from the Bank to the economy increase by a further £170bn.

Stimulation

The era of extraordinary economic times is certainly not over. "Normalisation", for the moment, is dead.

Will it work?

First, such a significant move is likely to boost confidence for businesses and consumers - and for an economy facing uncertain times, that is important.

The rate cut will reduce costs for some mortgage holders on tracker rates, which could encourage more spending.

And the fact that borrowing is now so cheap could stimulate house purchases.

As well as business investment.

But the Governor of the Bank of England knows he is not Superman, even if he is willing to rip off his shirt to show his monetary muscles.

Hoards

The supply of cheap finance has not been the fundamental problem facing the economy over the last month.

Companies are sitting on hoards of cash already.

Uncertainty over the Brexit process, worries about productivity, a general lack of demand and continually delayed investment decisions, for example in major infrastructure projects, are the issues weighing on confidence.

And for most of these issues it is the fiscal policies of the government, not the monetary policies of the Bank, which will make the difference.

Philip Hammond has already suggested he is considering a "fiscal reset".

In his letter to the governor of the Bank today, the chancellor says he is "prepared to take any necessary steps to support the economy and promote confidence".

Hopes

That could mean tax cuts to stimulate consumer spending and more borrowing and more government spending than George Osborne ever envisaged when he was the resident of Number 11.

Mr Hammond is unlikely to say much more about the detail of the government's new fiscal policy until the Autumn Statement in November or December.

By then there may be some evidence that the UK economy is stabilising thanks to the monetary stimulus announced today.

And greater political certainty about the UK's economic policies and the country's relationship with the EU.

That, at least, is what Mr Carney is hoping.