'London is most educated city in Europe'

- Published

Is London going to be a new kind of city state, based on a graduate economy

Where in Europe would you expect to find the highest concentration of graduates?

Would it be a particularly earnest quarter of Oslo? Or an erudite corner of Finland or Germany?

The answer - by a considerable distance - is London. In parts of London, more than two in three adults of working age, have a degree or higher education equivalent.

It is above anywhere in the European Union and unlike anywhere else in the United Kingdom.

It suggests how this mega-city, drawing talent from around the globe, has become a different type of economy. It's a city state of the digital age, trading in ideas.

And if London appears to have a different set of cultural, political and social attitudes, maybe education is part of the explanation.

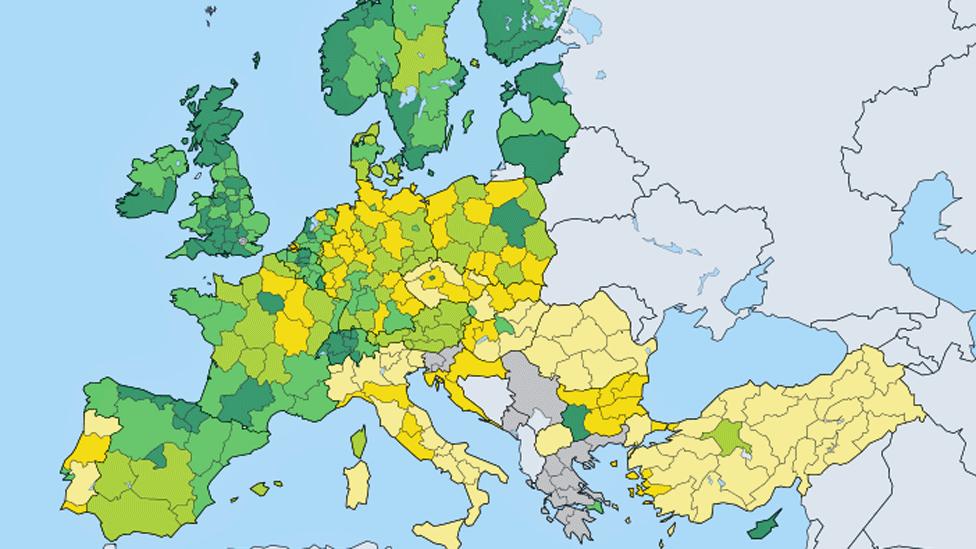

The highest concentration of graduates in Europe is in London

Most international comparisons of education are at national level. But Eurostat, the statistics arm of the European Commission, produces figures that drill down to regions and cities.

These have been updated over the summer, showing the position in 2015, and it shows that London occupies four of the top six regions for the most graduates, external.

The highest concentration of graduates is 69.7% in "inner London west", an area including Camden, the City of London, Kensington and Chelsea, Hammersmith and Fulham, Wandsworth and Westminster.

In second place is "inner London east", with 58.3%, including Haringey, Islington, Hackney, Newham, Lambeth, Lewisham, Southwark and Tower Hamlets.

Two other clusters of London boroughs to the south and west of London are in third and sixth place.

The nearest rivals are a region of Belgium to the south of Brussels and the Norwegian capital, Oslo, both about 54%.

Graduate levels across Europe mapped by Eurostat: Higher levels are green and lower are yellow

Finland, often seen as Europe's highest performer in education, sees its capital Helsinki in 9th place (51%) and Zurich (50%) in Switzerland is 11th.

The highest point in France is the Ile de France region, including Paris, which stands at 46%.

If you step out of London into Kent, the level of working-age graduates falls steeply to about 36%.

At the lower end of the spectrum are regions of Romania and southern Italy, where the proportion of graduates can be 15% and lower.

Here are some of the graduate levels, for the 25-to-64-year-old population:

Inner London west, 69.7%

Oslo 54%

Stockholm 49%

Madrid 47%

Ile de France 46%

South and eastern Ireland: 45%

Prague 40%

Berlin 37%

Kent, England 36.3%

Andalucia, Spain 28%

Picardy, France 24%

Lazio, Italy 23%

Saxony-Anhalt, Germany 23%

Southern Portugal 18%

Puglia, Italy 13%

So how does London do so well? How does it end up with a working population with more degrees than a box of compasses?

The Eurostat analysis shows as a starting point that England has a relatively high average level of graduates. It's not as high as Scandinavia, but it's not that far behind.

And topping it up even more, London is the highest performing area for education in England - with rising numbers going to university, even among disadvantaged families.

Oslo and the Scandinavian capitals are behind London in graduate numbers

If this creates its own local hotspot, London's graduate numbers are boosted even further by the many highly qualified graduates who come from other parts of the UK and many more who come from other countries.

These might be working in professional jobs in the City or they might be serving coffee in the West End, but they're part of the spike in graduate numbers.

More stories from the BBC's Global education series, external looking at education from an international perspective and how to get in touch

Another snapshot from the Eurostat figures shows how this trend could be accelerating even further - and how a gap could be widening with other parts of the country.

An analysis of graduate numbers among the 30-to-34-year-old age range shows that below the surface of an overall rise in graduate numbers in recent years there are some big regional differences.

London is part of a rising tide that has seen more students across much of northern and eastern Europe.

The level of graduates has been falling in parts of Spain

But there have been pockets of decline in parts of north-east and south-west England, eastern Germany, north-west France and parts of Spain.

What's interesting about these figures is that they are not showing what schools and colleges produce, but what local economies can sustain when people have left education.

After last week's A-level results, record numbers of UK university places were offered and this increase - and the accompanying cost in fees and loans - has prompted questions about whether there could be too many students and the economic benefits could be eroded.

Last week, the Institute for Fiscal Studies produced a mixed forecast on this. Looking at previous expansions in student numbers in the 1980s and 1990s, researchers found that graduate earnings had not been reduced.

London attracts graduates from other parts of England and from other countries

But there were warnings that at some point this would stop and that numbers could not rise indefinitely without limiting the value of degrees.

The evidence suggested by the Eurostat figures raises a more complex question. It shows how wide the differences can be within countries.

How will these increasingly different economies co-exist? What will be the tensions between graduate-dominated, wealthier cities and other poorer regions where traditional industries have declined?

Should this polarisation be encouraged as an economic driver - or discouraged as a form of widening inequality? If graduate levels are almost 70% in inner London and 36% in nearby Kent, how do you debate the idea of there being too many or too few graduates?

The OECD's director of education, Andreas Schleicher, says the rise of graduate cities is the "new normal" for the modern economy - and he says that finer-grained data could probably find places with graduate levels of 80%.

He says this is driven by both supply and demand - rising numbers of families wanting their children to go to university and high-wage economies in cities drawing these extra graduates.

Mr Schleicher says arguments about whether there are too many graduates will become as outdated as debates about whether all young people should get school qualifications.

"If we had had this discussion 100 years ago, people would have asked whether cities needed school graduation rates of over 70%.

"Today higher education is the new normal that reflects labour demand in the high-wage, knowledge-based economies of large cities."