How your social media reputation could secure you a loan

- Published

Africa's youngsters are far more likely to access financial services via mobile than bank branch

Traditional banking in Africa has failed - 80% of the continent's 1.2 billion people do not have a bank account or access to formal financial services.

So mobiles and web-based services are stepping in to fill the gap. But there is much more to Africa's financial services story than M-Pesa, the wildly successful mobile banking platform launched in Kenya and Tanzania in 2007.

For example, Nigeria's Social Lender looks at borrowers' social media profiles to assess their creditworthiness.

One of the issues lenders face is that it is near impossible to obtain adequate data about people, particularly in rural areas. So mobile and web are proving useful ways of gathering it.

Social Lender uses its own algorithm to assign a "social reputation score" to each user, with "social guarantors" acting like referees validating their trustworthiness.

As the youth-orientated website strapline has it: "Get rep, get cash, stay fly".

"The solution is designed to bridge the gap of immediate fund access for people with limited access to formal credit," says co-founder Faith Adesemowo.

Social Lender's Faith Adesemowo says online reputation is a useful indicator of creditworthiness

"Loans are guaranteed by the user's social profile and network, allowing users to borrow from banks and other financial institutions based on their social reputation," she says.

Social Lender currently has more than 10,000 registered users taking out loans of up to 10,000 Naira (£24) with a default rate of less than 4%.

Users can withdraw cash loans via bank accounts or mobile money.

"We solve the problems of prohibitive cost to serve the market, inadequate financial history, unreliable credit score and lack of collateral for these people that hitherto prevented our partner financial institutions from serving this market," says Ms Adesemowo.

Data intelligence

Mobile phone data is also helping to give lenders and other financial service providers useful information about potential customers.

Based in Cape Town, Jumo partners with mobile operators in countries like Kenya, Tanzania and Zambia, to gain access to data on how people use their phones.

Its algorithms analyse a person's smartphone usage - how much they spend on airtime, how they use their mobile money wallet - to come up with a "Jumo score", which rates their creditworthiness.

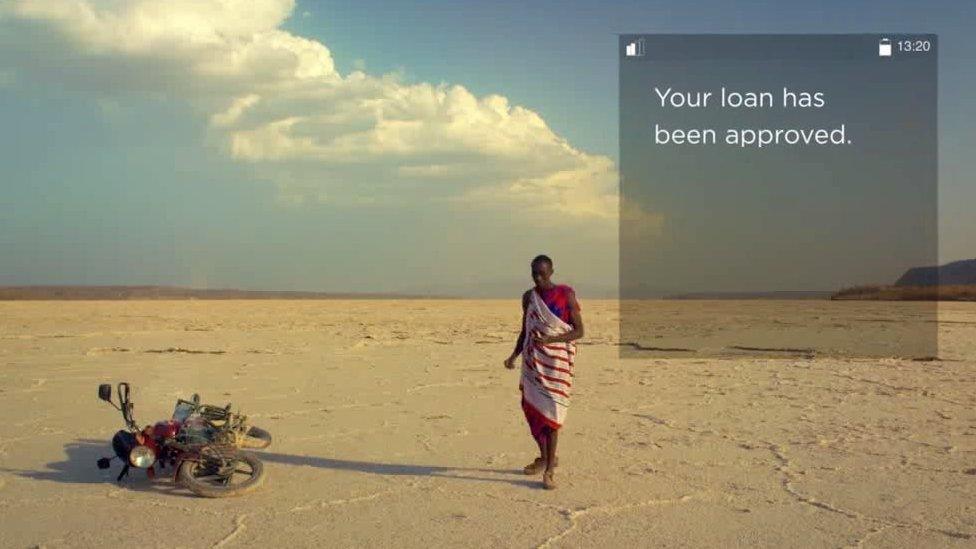

Jumo can issue instant loan approvals to merchants and consumers alike

Users can then apply for loans from conventional lenders through Jumo and have the cash sent straight to their phones.

"A $20 [£15] loan that can be accessed without collateral in the middle of the night in a rural village can mean the difference between getting a sick person to hospital and going without medical care," says Andrew Watkins-Ball, Jumo's chief executive.

"For a micro-entrepreneur who deals in single-digit dollar amounts, a similar amount can have a major impact on their ability to buy stock effectively at greater volumes and lower prices."

Smartphone adoption is still very low among poorer communities, he says, so the technology has been to run equally well on simple, so-called "feature" phones as well as on smartphones.

Jumo says small loans for bike repairs, say, can be sent instantly to mobiles

Using the data gathered, Jumo can target users with products they are likely to need. Three million people have used the tech company's services since it launched in 2015 and it makes up to 50,000 loans a day.

Providing data on informal and rural traders to enable access to credit is key for Africa's development, says Hendrik Malan, operations director at research consultancy Frost & Sullivan Africa.

"This will give rise to an enormous micro-lending market across the continent," he says.

Sending money home

Mobile and web tech is also helping the 30 million Africans living abroad send money home more efficiently.

This African diaspora sends more than $40bn (£30bn) back home each year. But costs are prohibitive: the World Bank says Africans pay an average of 9.74% in fees for every transaction with the likes of Western Union and Moneygram.

Now these money transfer giants are being challenged by nimbler start-ups.

One of these is Ugandan company Redcore Interactive, whose service, Remit, enables people to send cash via debit or credit card to relatives and friends in Uganda, Kenya or Rwanda at the click of a button, straight to their mobile phones.

Stone Atwine says Remit makes money transfer "simpler, faster and more convenient"

Recipients can then use the money to pay bills direct from their mobile wallets or make a cash withdrawal at any mobile money agent.

Founder Stone Atwine says Remit offers significant time and cost savings, bypassing physical infrastructure for a fee of 4.99% of the transaction amount.

"The reduction in overheads allows us to provide remittance services at a significant discount to existing providers," he says, adding that millions of dollars have already been transferred through Remit.

"Sending money within and to Africa is expensive and inconvenient. We solve this by building products that make mobile money systems interoperable across the continent."

Partnerships

The growing influence of such "fintech" services across Africa would appear to pose a threat to traditional branch-based banks.

Yet this doesn't seem to be the case.

Speak to many fintech entrepreneurs and they will say that their services are complementary to established banks, not a threat to them. Indeed, many banks are partnering with African fintech start-ups rather than competing with them.

Established banks have access to customers, something fintech start-ups lack. So co-operation makes more sense, Frost & Sullivan's Mr Malan believes.

And it is this interplay between new tech and established bank networks that could see many more millions of Africans gaining access to much-needed financial services.