How farmers can end land disputes and produce more food

- Published

Many of the millions of smallholder farmers in Africa are unsure whether they own their land

Farming can be a tough enough business at the best of times, but imagine not being able to prove that the land you farm is even yours.

In Ghana, for example, only 10% of smallholder farmers have any kind of certificate documenting their ownership rights.

Not only does this put them in a vulnerable position, it can often lead to disputes. And if your land is the main asset you want to borrow against, getting a loan can prove difficult, too.

So tech company Landmapp has come up with an innovative mobile platform that uses GPS location functionality to map and survey smallholder farmers.

Farmers receive a certified plan of the land and land tenure documentation signed by the surveyor, chiefs and high court.

"Land tenure insecurity is a core barrier to land investment and farming," explains Thomas Vaassen, Landmapp's co-founder and chief technical officer.

Landmapp makes an accurate digital survey of the farmer's land

"Without proper documentation, there is a real risk of losing the rights to a land parcel. Also, without documentation it is often not possible to access financing, as the document is the only collateral at hand for most farmers."

The company started operations in Ghana earlier this year and has already completed more than 1,000 land maps. It says 80% of traditional chiefs are interested in the service.

Smart contracts

Disputes can also occur between farmers and food companies who buy their produce.

These arrangements have traditionally relied on a large element of trust on both sides. But sometimes producers don't get paid when food companies think farmers haven't delivered what they promised.

So Freshmarte for Provenance has developed a mobile app that enables food companies and farmers to operate digital smart contracts based on blockchain, the technology underpinning the Bitcoin digital currency.

Freshmarte's app creates smart digital contracts between farmers and buyers

These contracts are recorded in an encrypted, decentralised ledger that cannot be tampered with, so there can be no dispute about the agreements or whether the terms have been fulfilled or not.

The app integrates satellite imagery to monitor the progress of farming projects. And following harvest, the price of produce is fairly determined by an algorithm.

The tech has other uses, too.

Freshmarte is based on open data, allowing anyone to view the source of the products being sold. Buyers can be sure that no child labour was used, for example, or that producers are receiving a fair wage.

Smart contracts can ensure farmers receive a fair price for their produce

"Our platform, with independent open data APIs [application programming interfaces], allows any concerned individual to research how, when, where, under which labour conditions, and price in respect to trade, the food on their table was grown, packaged, transported and delivered," explains founder Job Oyebisi.

The app is currently being trialled in southern Nigeria by British American Tobacco, and goes live country-wide in November.

A problem shared

Of course, it's not just hi-tech solutions helping farmers. Lo-tech phones have given them better access to live market prices, weather forecasts, and, crucially, advice for many years now.

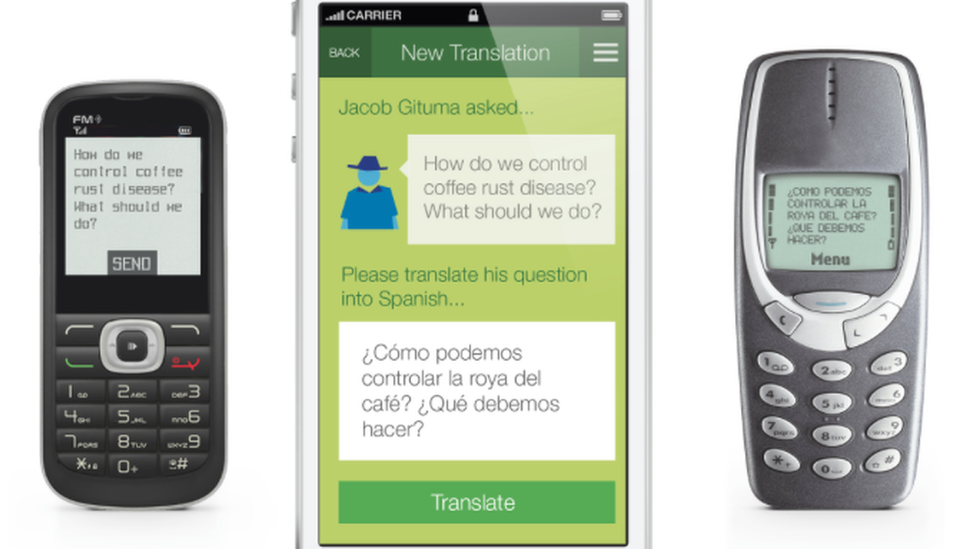

One company, WeFarm, operates a peer-to-peer knowledge exchange service via SMS text message, allowing farmers to ask questions of other farmers.

Its algorithm routes the question to the most relevant farmers, based on their location and expertise, for example.

When Ugandan farmer Erick Beinenama's chickens were dying from coccidiosis, he turned to WeFarm in a bid to save them. Another chicken farmer saw his SMS, gave him advice, and Mr Beinenama managed to save his remaining 23 chickens.

The WeFarm text message service provides useful advice to farmers from farmers

"With farming, you need knowledge from other farmers for better yields," he says. "Without the information from WeFarm, I would have lost all of my chickens."

Each farmer receives on average three to five answers within a couple of hours, and often farmers from other countries begin sending in advice within 24 hours.

Until now, rural farmers typically relied on government field officers for assistance if they had a problem with their crops or livestock. Visits to rural villages from these officers are often only once a month - enough time for all of a farmer's animals to die, or their crops to fail.

"Technology opens up lots of opportunities, whether that is solving a problem on their farm, finding a market for produce, or being able to enhance their resilience to climate change," says Kenny Ewan, WeFarm's founder and chief executive.

"These small differences can make a huge impact on smallholders' livelihoods."

Finance for farming

In the meantime, improving farmers' access to financial services - and financial security - also needs to be a priority for technical innovation, says Ross Baird, chief executive of investment and business training organisation, Village Capital.

With around 33 million small farms producing up to 90% of Africa's entire agricultural output, Mr Baird argues it is important to help farmers build their wealth and achieve financial security.

Nearly two-thirds of the rural population in sub-Saharan Africa live on less than $1.25 (95p) a day.

The majority of people in Africa earn money from farming

"Low-cost smartphones have given farmers access to financial services they never had before. But other tools, such as access to credit, savings, investments, and income-smoothing mechanisms require data that is currently too expensive for the plans that farmers have," Mr Baird says.

Village Capital recently ran a business accelerator in East Africa focusing on these challenges.

He says Africa needs better infrastructure, and preferably free internet, if farmers are to benefit fully from new technology.

"Ultimately, we will be successful when we see the average farmer earn a living wage and have financial security," he says.