Want to age well - how about never retiring?

- Published

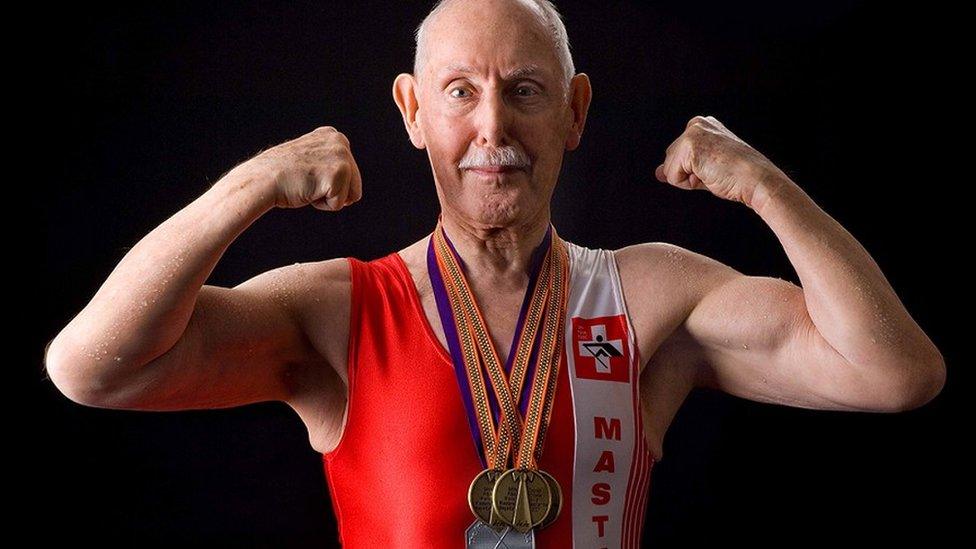

"Even at 87, I wanted an Adonis body," says Charles Eugster

Charles Eugster isn't your average professional.

True, like tens of thousands of others in his Swiss hometown of Zurich, he heads to his office most mornings, a commute that involves a walk up a steep hill for 10 minutes, a half hour train ride, followed by a 10-minute tram journey.

Once there, he works at updating his website, writing, and conducting research into ageing. What makes him exceptional is that he's doing all of that at the age of 97.

But could he be trailblazing for the rest of us?

He certainly thinks so. Dr Eugster attributes his longevity to the fact that - bar a pause in his early 80s - he has never really stopped working, and in his late 80s decided to focus on his fitness.

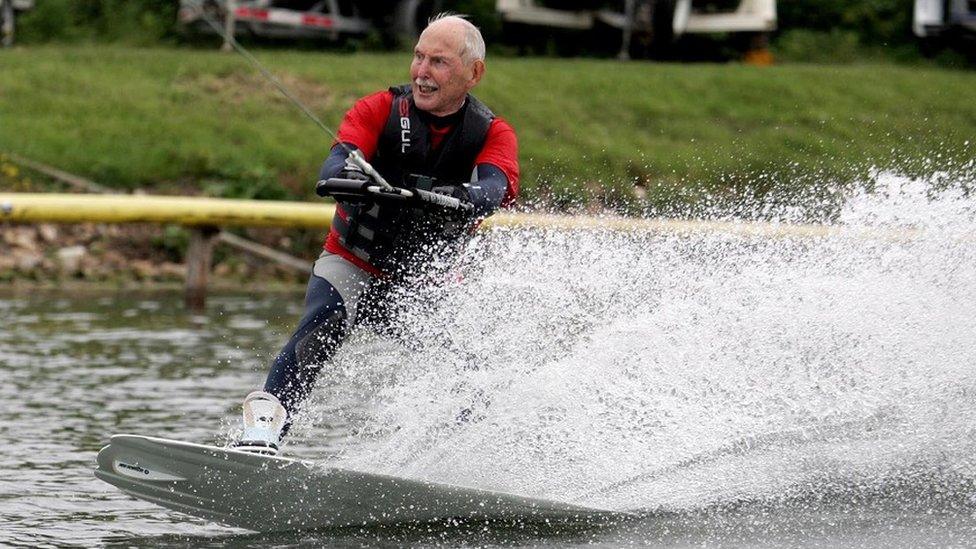

He worked as a dentist until he was 75, and is now an athlete who trains three days a week, holds the indoor 200m and outdoor 400m sprint world records for men over 95.

Charles Eugster took up sprinting at the age of 95

He is competing in the 100m, 200m and long jump at the British Masters Athletics Championships in Birmingham this weekend.

"I'm not chasing youthfulness. I'm chasing health. People have been brainwashed to think that after you're 65, you're finished. But retirement is a financial disaster and a health catastrophe," he says.

Ageing population

In that he echoes similar concerns voiced by the likes of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as well as many pensions and retirement experts, although perhaps they use less alarmist language.

As the baby boomer generation retires, many developed societies will have to focus on preventing old-age poverty

"The reduction of old-age poverty has been one of the greatest social policy successes in OECD countries," a recent OECD report noted, external.

But it added: "As the baby boomer generation retires and pension systems continue to be reformed, the focus on preventing old-age poverty will become sharper and sources of income in old age other than those from pension systems would have to be considered."

For Charles Eugster, those other sources of income can only mean working well into our twilight years.

Find out more:

How to survive at work: The Business Daily team explores life in the office

Click here for more programme highlights

We're used to hearing about mounting pension liabilities in the industrialised world, what's often referred to as the pensions "time bomb".

An ageing population coupled with falling fertility rates and thus a shrinking workforce from which to extract taxes, means governments and companies are struggling to pay out the pensions of the elderly.

Compounding the problem is the fact that most of us are living longer than ever before as well as evidence showing that retired people have more health problems, external.

The UN estimates that globally, the number of those over 60 or over will more than double by 2050, external and more than triple by the end of this century.

Some experts argue we will need to keep reinventing ourselves to stay ahead of technology

What's more, about half of all babies born in industrialised nations today can expect to live to 100 years.

"People seem to forget how old we are becoming," Charles Eugster says. "How on earth do you think we are going to pay for all those years of doing nothing?"

Rethinking life

It's prompted some to argue that we need a fundamental rethink of the way we live and work. Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott, professors at the London Business School have done just that in a book, The 100-Year Life, external.

They argue that that if turning 100 becomes normal, then we have to discard our idea of a traditional "three-stage life", one in which education is followed by work and then retirement.

Half of all babies born in industrialised nations today can expect to live to 100

If our working lives become a seven-decades long affair, then we cannot rely on a single period of education to prepare us for it. Instead, they argue, we will need to constantly retrain and reinvent ourselves to stay ahead of technology and the demand for changing skill sets.

It's a daunting proposal, and one that would pile the pressure on all of us to "age well" - to stay robust and healthy in order to remain a productive member of the workforce.

It is this idea of "ageing well" that Anne Karpf, a sociologist at London Metropolitan University and author of How to Age, objects to.

"People are trying to overturn the stereotypes and they erect new norms instead," she says. "We've got to be very careful not to be prescriptive in our ideas about ageing."

Challenging stereotypes

At the moment, the stereotype is that the elderly are often too frail to work and are therefore forced into a dependent position, either in terms of the pension they rely on or the help they require from family or social institutions.

Whether you have a healthy old age depends a lot on your income level

But Anne Karpf says even those existing stereotypes are wrong. "All of us, as we go through life, have periods of fragility and dependency," she says. "This idea that the young are independent and the old are dependent is a gross simplification."

So are we living healthier as well as longer lives, or are our additional years spent in poor health? There appears to be considerable debate surrounding those questions.

Research by the National Institute on Aging, external (NIH) in the US, says it depends on how rich you are and your ethnic background.

Richer people live longer, healthier lives and it found, among other things, that older adults in the US were less healthy than their British counterparts at all socioeconomic levels.

"There is no physiologic reason that many older people cannot participate in the formal workforce," the NIH report concluded, "but the expectation that people will cease working when they reach a certain age has gained credence over the past century."

That expectation started in earnest after World War Two, when industrialised nations created modern pension schemes. But those pension schemes were created when life expectancy was a lot shorter.

Charles Eugster is not your average 97-year-old

In 1960, average life expectancy, external in the UK and the US was about 70, with many men retiring at 65. Today people in these countries are expected to live to about 80 - yet the average retirement age is 64.

"It is ironic that the age at retirement from the workforce has been dropping at the same time that life expectancy has been increasing," the NIH report said.

'Vanity is your friend'

With all the talk of a pensions time bomb, the economics does not bode well for those of us looking forward to a long, financially stress-free retirement. In fact, the risk is we may start to see our increased longevity as a curse rather than an achievement.

But is the answer to spend our seventh, eighth or ninth decades in the gym, like Charles Eugster?

For those of us horrified at the suggestion, Dr Eugster has several other proposals.

As his age group grows in number, he wants better services for them, things like dating agencies, business schools and training facilities for the over 65s - anything that helps the elderly remain engaged and productive which in turn, he believes, keeps them healthier.

And on that last point, he reckons vanity is your best friend.

"Even at 87, I wanted an Adonis body, in order to turn the heads of the sexy, young 70-year-old girls on the beach," he says.

"I wanted a six-pack, but my coach said that we must first work on my bottom, which she said was a catastrophe."

For more from Manuela and the Business Daily team, listen at 08:32 GMT each weekday on BBC World Service or download the podcast and check out episodes and programme highlights here.