US farmers go 'natural' for profits

- Published

An estimated 80% of beef cattle feeding operations in America farmers use artificial growth hormones to make the animals grow faster. But the practice is rare in the country's north-eastern states. Hilary Niles visited one farm in Vermont to find out why.

Thirty-five years ago, a professor moved to a historic farm on 600 acres of rolling hills overlooking the sparkling Lake Champlain in Vermont.

His family built the largest beef cattle feedlot - a place where cattle are fattened for slaughter - in the north-east United States, a crowning achievement in its time.

Months before he died at the age of 59, Paul Saenger passed that farm on to the son of one of his former college students.

Today, 29-year-old Wallace Greenwalt is also finding success on Cream Hill by running the farm his own way, in line with changing consumer demand.

Where Paul Saenger had raised about 1,000 head of cattle and used artificial growth hormones to do it, now Wallace raises just 600 cattle, free of hormones and antibiotics.

Wallace Greenwalt has changed the business model of his farm

He sells the animals for meat, mostly to local packers, who market the food as "natural".

"The local buyers, they hear from their customers that they want antibiotic and hormone-free 'natural' cattle," Wallace says. "And so that's what they want to buy, and so that's what I'm happy to sell them."

Changing tastes

The US Food and Drug Administration does not regulate use of the term.

"Natural" can describe just about anything legal. But when applied to meat, it often refers to animals that were raised without hormones or antibiotics.

Find out more

Listen to Hilary Niles' report on The Food Chain: Naturally Misleading?

Watch: GM food: What's in a label?

Officials and many agricultural professionals stand by the safety of these products. Nonetheless, some researchers and a growing segment of the American public appear wary.

According to market research, external from a professional organisation for commercial meat buyers, demand for natural and organic meat has risen steadily in recent years. The percentage of shoppers who had bought natural or organic meat in a three-month period rose from 26% in 2012 to 40% in 2016.

Eric Mittenthal is vice-president of public affairs for the North American Meat Institute, external (NAMI), which co-publishes the survey. He says his members "strive to meet what the market demands, what consumers are most interested in".

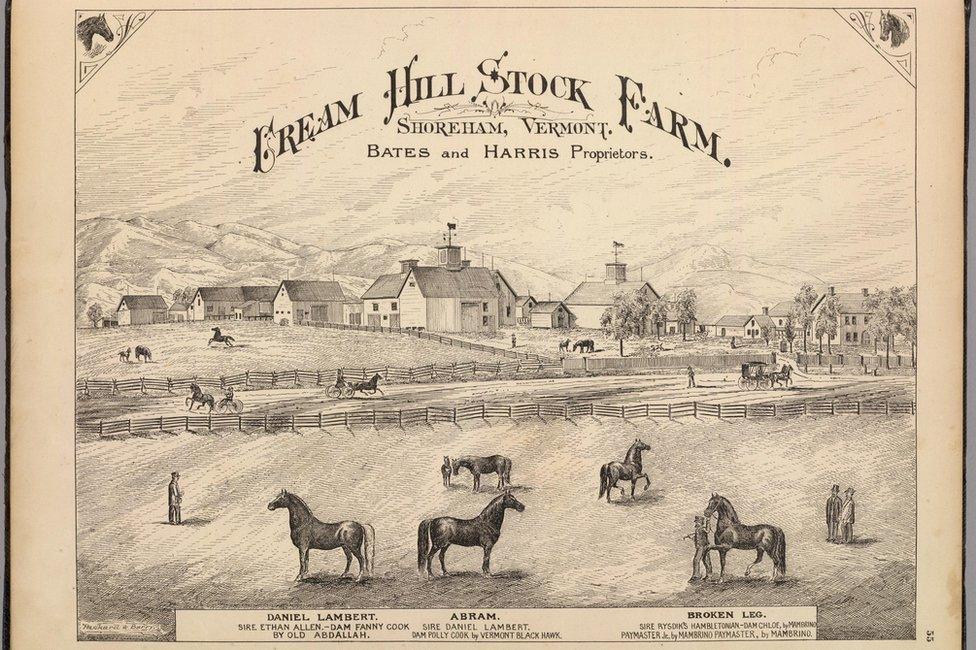

Changing times: this image of Cream Hill Stock Farm was published in an atlas of Vermont from the 19th Century

So does Wallace. But, in addition to consumer demand, he says his own philosophy prompted his switch to a natural feedlot. "I just don't think you really need to mess with cattle," he says.

"If you leave a cow and her calf alone, as long as they have enough grass and water, they'll do pretty well. So you don't need to jab 'em with extra boosters."

Wallace estimates that it costs about 5% more to farm this way because, without extra growth hormones, animals simply take longer to fatten.

When that time comes though, Wallace is paid about 20% more. This equation allowed him to reduce Cream Hill's herd. He runs the operation today with help from his father and a single employee.

A matter of scale

Cream Hill Stock Farm's feedlot is still large by Vermont standards, but it is tiny compared to the American Midwest, where farms can house thousands or even tens of thousands of cattle.

Wallace Greenwalt says he became a farmer because he liked science, animals and plants

At that size, everything changes, says Joe Emenheiser. As a former livestock specialist for the University of Vermont Co-operative Extension service, he advised farmers on raising their livestock.

Joe studied animal science in the Midwest, and he's sheared sheep professionally, worked as a butcher, managed two different farms, studied quantitative genetics, and penned a dissertation related to grass-based beef systems, economics and production efficiency.

"In the commodity system, where everything is based on pretty fixed, pretty low sales prices, so much more of making it or breaking it depends on production efficiency," Joe says.

"How much feed is required to produce the same amount of product? How much space? Time? Diesel fuel? How quickly do those animals grow?"

Different equation

According to the Iowa Beef Center at Iowa State University, those animals grow faster with growth hormones.

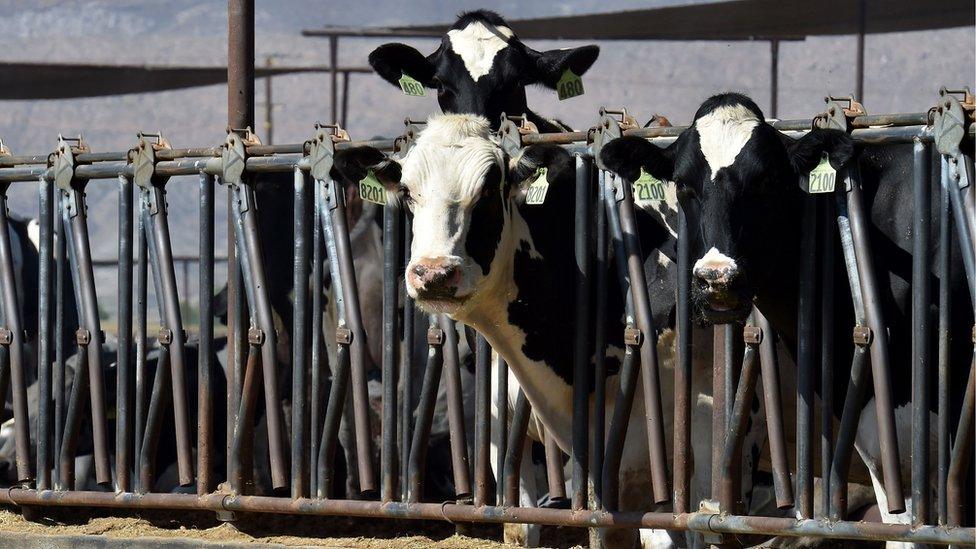

At larger farms it may be most cost-efficient to use growth hormones (file photo)

"Depending on the implant, and the age and sex of the animal, implants will improve growth rate from 10% to 20% and decrease the cost of beef production by 5% to 10%," wrote Dan Loy, the center's director, external.

Multiply that by 10,000 head of cattle and you've got a different equation to the one Wallace Greenwalt uses. He is raising his cattle in a different landscape - both topographically and economically.

Joe Emenhesier says that in smaller New England states like Vermont, a beef producer's financial bottom line is buoyed more by price premiums than production efficiency.

Cost v characteristics

NAMI's market research predicts consumer demand for "natural" products will continue to grow.

Their research suggests 40% of shoppers have bought natural or organic meat in the last three months to avoid hormones or antibiotics, which leaves 60% of Americans who haven't.

Some consumers may not mind the modern conventions of farming when it comes to buying their meat

Some shoppers probably can't afford natural products, while it's likely others don't think the premium price is worth paying.

"Some consumers want to have the most inexpensive meat possible," Eric Mittenthal says.

Wallace Greenwalt can relate to that. As a beef producer, he doesn't buy meat at the grocery store often. But on occasion, he says, he'll pick some up in the course of his food shopping.

"There's usually… a small case of organic, but then there's just the typical USDA (US Department of Agriculture) Choice regular beef," Wallace says. "When I do buy beef that's usually what I get, because it's cheaper and it's perfectly good."

For these price-conscious shoppers - even those among them who make a living farming "natural" meat - it's industrial-scale, conventional agriculture in America's current food system that delivers.

Hilary Niles is an independent journalist, data journalism consultant and researcher based in Vermont.