How disease testing tech is saving lives faster

- Published

The GeneXpert machine can test a cartridge for the Ebola virus within 90 minutes

When a nurse at Monrovia's Redemption Hospital in Liberia fell ill, the doctors thought she had typhoid fever.

But three days later, they realised it wasn't typhoid - it was the deadly Ebola virus.

This delay, says Dr Jude Senguku, meant that his flatmate - the hospital's senior surgeon - caught the disease from the woman and died, along with two nursing staff.

It was a harsh lesson in the crucial importance of fast - and accurate - diagnostics.

Mis-diagnosis, panic and misinformation led to people in Liberia staying away from hospital, he says. Some would misrepresent their symptoms to avoid being sent to Ebola isolation units.

"To rule out - and rapidly screen for - Ebola became important," says Dr Senguku.

'Very critical'

Fortunately, Redemption Hospital received one of the first machines for Ebola testing - a piece of kit called GeneXpert that could provide a cheap and accurate diagnosis within 90 minutes.

Given that Liberia had only 50 doctors for 4.3 million people at the outbreak of the epidemic, such easy-to-use equipment proved crucial in the fight to contain the disease.

As it was, Liberia was hit hard, officially recording 4,809 deaths from Ebola, the most anywhere in the disease's 2014-2016 outbreak.

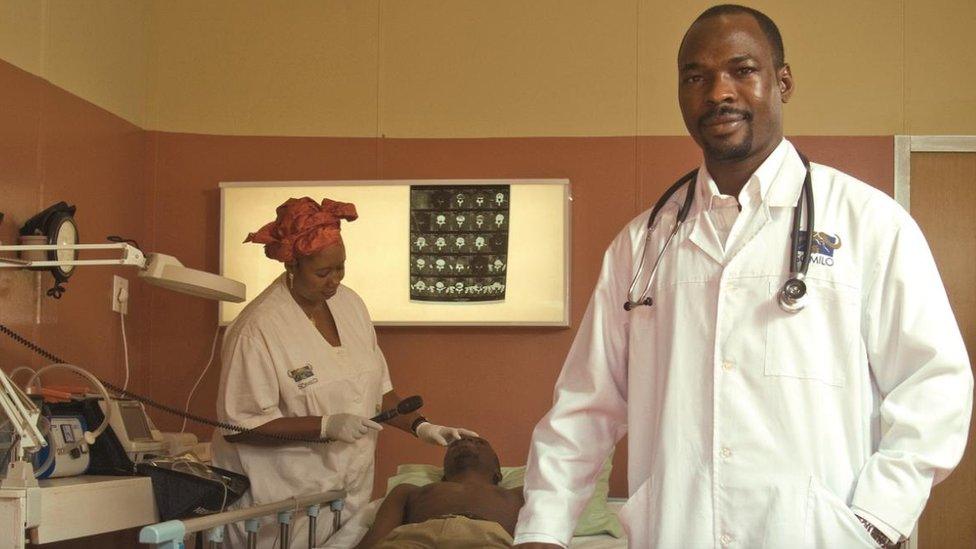

Dr Senguku of Monrovia's Redemption Hospital says rapid testing for Ebola has saved lives

Since then, Dr Senguku says the diagnostic technology has been "very critical" in reducing false Ebola scares and restoring confidence among the people of Monrovia.

Dr David Persing, who created the rapid diagnostic test, is executive vice president of Cepheid, a Silicon Valley-based biotechnology company. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation contributed $3.5m (£2.7m) to the project.

Simply put, the machine measures the nucleic acid in a patient's specimen - spit, say - and detects a disease's signature DNA sequence. This method, called a nucleic acid amplification test, can detect extremely low levels of a pathogen, along with drug-resistant variants.

The test cartridge costs $10 for poorer countries, while the machine itself costs about $17,000.

'Easy to use'

Portable, low-energy diagnostic kits that are easy to operate are particularly important in areas with limited access to power or expensive laboratory equipment.

Simple malaria tests detecting antigens, and HIV tests which look for antibodies - like those developed by Massachusetts-based medical technology company Alere - can test "rapidly far from a lab", says Dr Megan Coffee, an infectious disease specialist and technical advisor at the International Rescue Committee.

She says many of these "point of care" tests - most of which consist of a membrane in a plastic cassette - are as "easy to use as a pregnancy test stick, which require no electricity, no refills, and can be carried and used by mobile community health workers."

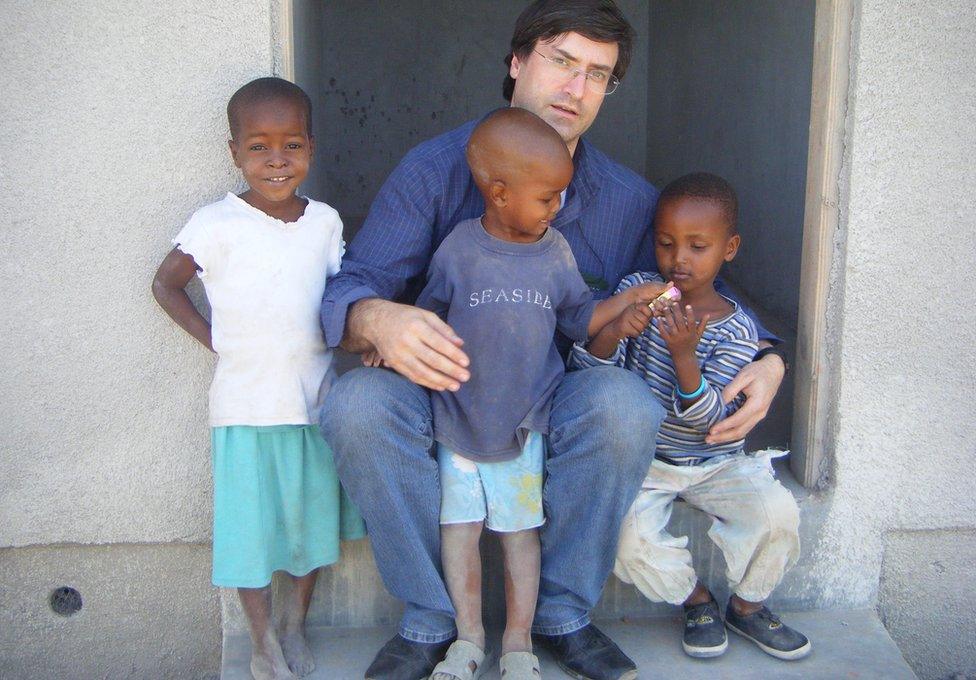

Dr Manirou of miner Randgold Resources tests employees and villagers for a range of diseases

This is useful for big mining companies and other major employers.

For example, gold miner Randgold Resources' Loulo-Gounkoto mine is a five or six hour drive away from the nearest Ebola assessment centre, says Dr Haladou Mahaman Manirou, who works for the company.

An on-site clinic monitors employees and people from neighbouring villages. Along with Ebola, other infectious diseases, like malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis, are the "main burden" on his employees' health, says Dr Manirou.

Malaria affected 39% of Randgold's workforce in 2015. The figure was 69% in 2011. A 15-minute diagnostic test, developed by Flow, a US biotechnology company, has helped quickly identify and treat cases, he says.

Malaria, spread by the Anopheles mosquito, killed more than 430,000 people in 2015

And now the next step for diagnostic technology is to "test for multiple causes of, say, a fever", she says.

For example, Singapore-based medical technology company STMicroelectronics has developed a "Lab-on-Chip" platform, which is the size of a fingernail and can test for multiple tropical diseases in a single blood sample.

The lab on a chip is slightly more expensive than a GeneXpert cartridge - roughly $100 - but doesn't require a machine.

Remote diagnosis

As well as on-the-spot testing, diagnoses can also take place thousands of miles away, thanks to internet technology.

Global Health Telemedicine, for example, run by Dr Michelangelo Bartolo, director of telemedicine at San Giovanni Hospital in Rome, has connected doctors in 19 health centres in Africa with 100 volunteer specialists in Europe.

Dr Bartolo's company helps diagnose diseases remotely

The average response time is "about three hours", says Dr Bartolo. In two years of operation, there have been 3,500 "tele-consultations", including 1,300 electrocardiograms.

His software includes a feature to allow African doctors to fill out information when offline, too, which is a useful feature in areas with patchy connectivity.

The need for speed

But battling the next epidemic after Ebola will require being faster off the block, says Dr Persing.

"To get started on test development in the middle of an epidemic just doesn't work," he says, adding his company doesn't have test cartridges for Zika, Lassa Fever, or "all the things that could come up".

A "just-in-time delivery" model would work better, he says.

If world health officials designated a list of critical infectious diseases, businesses like his could pre-manufacture and pre-validate agents for the test, and get regulatory approval for them, he believes.

The highly contagious Ebola virus killed more than 11,000 people in West Africa from 2014-16

"If you have an epidemic, you don't want to wait for six months or a year to have a test available," says Dr Persing.

Speedy diagnostics can also help measure the effectiveness of health campaigns, argues Prof David Alland, chief of infectious diseases at Rutgers Medical School.

"In some parts of Africa, it was thought major malaria intervention programmes weren't working," he says.

But it turned out doctors were incorrectly diagnosing malaria based on patients' clinical symptoms. More accurate diagnostic technology showed anti-malaria programmes were actually more effective than people believed.

So the more we know, and the quicker we know it, the more lives we can save.