What is fashion week for and why is it changing?

- Published

Jigsaw was showing at London Fashion Week for the first time

London's autumn fashion jamboree wraps up on Tuesday, with the last few catwalk shows and presentations.

But this year, as the staff collect up the champagne flutes and stack the chairs, the aftermath is not quite business as usual.

There has been much talk of the new "see now, buy now" trend that upends the traditional system whereby fashion houses showcase their new styles but only deliver them to the market several months later.

So what exactly has changed and why?

What is fashion week for?

London Fashion Week comes around twice a year (in September and February), and, as the people behind it are keen to emphasise, it is about a great deal more than hats and hem lengths.

Around half of Topshop's Unique collection was available for sale immediately after the catwalk show

It is the industry's trade show: new styles are launched, fashion journalists take copious notes, and buyers put in orders for stock.

According to the organisers, the fashion industry contributes £28bn to the UK economy and is growing, currently providing jobs for 880,000 people.

And in an ever noisier world, it can help let your voice be heard, according to Peter Ruis, chief executive of Jigsaw - showing at Fashion Week for the first time.

He says: "Twenty years ago, there were maybe 300 to 400 brands in Europe.

"Now, there are millions of brands everywhere, so London Fashion Week gives us a chance for four days to be on the top of the agenda."

So what is new?

In the old days, a designer would show new styles in the autumn that were meant to be worn the following spring.

February's fashion shows looked ahead to the coming winter.

It gave editors time to publish lots of glossy photos in monthly magazines and allowed the anticipation to build before the clothes arrived in store.

At London Fashion Week this February, Burberry, was the first to introduce the idea of "see now, buy now" or "runway to retail": showing products and then making them immediately available to buy.

Their collection, on Monday night, was billed as "seasonless" and "immediate", available globally.

Topshop and Jigsaw followed their example.

Burberry was the first major brand to say it was switching to a "see now, buy now" schedule

At New York Fashion Week a few days earlier, Ralph Lauren held its show on Madison Avenue, so once the runway had cleared, guests could be ushered straight into the brand's flagship store, where all the designs were immediately available to buy.

Tom Ford and Tommy Hilfiger have adopted the new timetable too.

Natasha Pearlman, editor of Grazia magazine, told BBC Radio 4's Today Programme that labels had realised it was just too hard to keep people excited about a design while they waited for six months.

"You're responding to what the consumer wants," she said.

"The consumer drives the profits... the more people you're talking to, the more the products are available to them, the more exciting it is."

But not everyone is keen on the idea.

"Fashion used to be a world of allure, and refinement and scarcity," says Patrick Grant, creative director of Savile Row tailor Norton & Sons.

"Personally, I felt there was something wonderful about this," he says/

"Now... there's fashion spam everywhere.

"And what this has done is turn Ralph Lauren and Burberry into [shopping channel] QVC.

"It's totally democratised, but my problem with it is, it's losing its allure."

What has brought this on?

"Fast fashion" from brands such as Zara and H&M mean that once the big name designers have shown their hand at Fashion Week, ordinary shoppers have to wait only a few weeks before High Street retailers are offering the colours and shapes they are craving.

Not all catwalk styles are easy to wear, but they are now easy to buy

Then there is the internet.

Fashion journalism is also undergoing a revolution as independent bloggers or "influencers" play an ever greater role in telling consumers what is hot and what is not.

If a high-end label waits six months before its lines arrive in the shop, it risks looking dated as the internet and the High Street have long ago been there and done that.

Moreover, as the fashion industry becomes ever more global, the idea of designing for an upcoming "season" stops making any sense.

There is a market for winter coats in Australia just when Americans are investing in strappy summer dresses.

Guests at the Ralph Lauren show at New York Fashion Week were taken straight from the runway into the store

What is not changing?

Some things are not changing.

There is the biannual debate over the influence of super-skinny models and the lack of ethnic diversity on the catwalk.

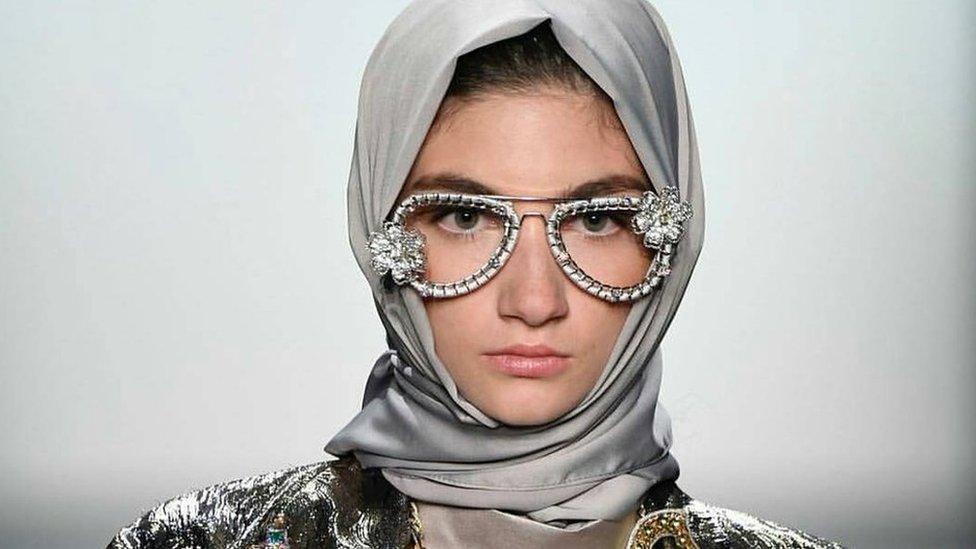

Designers are still making a splash with outlandish garments - not because they think consumers would ever wear them but because it helps them to establish a brand identity and make them memorable.

And newspapers and magazines, whether in print or online, are as keen as ever to fill their pages with glossy pictures of celebrities ranged along the fashion front rows.

- Published16 September 2016

- Published8 September 2016

- Published5 February 2016

- Published20 September 2016