Football's third-party ownership rule explained

- Published

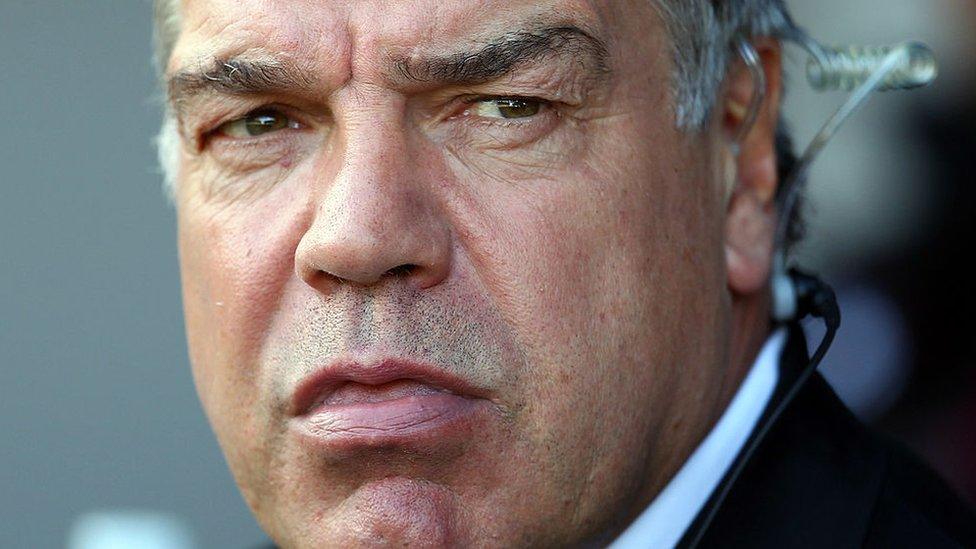

The news that England manager Sam Allardyce is being investigated over allegations that he offered advice around third-party ownership (TPO) rules has brought a controversial topic back into the spotlight.

The Telegraph newspaper , externalsays it has footage from August of Mr Allardyce meeting men claiming to represent a Far East firm where he appears to say third-party ownership rules can be avoided.

The 61-year-old has yet to respond to the allegations, while the FA has asked to see the paper's filmed recordings.

Third-party ownership of players is whereby private investors, it can be an individual, company, or fund, own part of a player's economic rights.

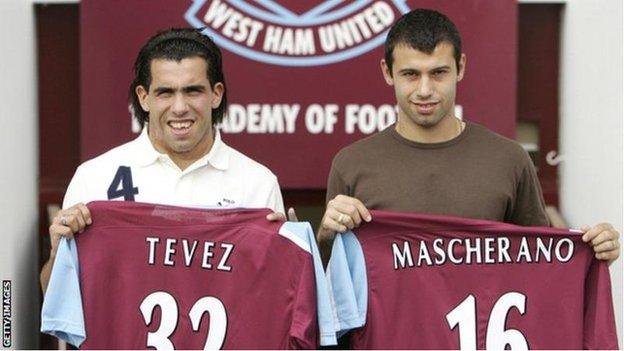

It first came to attention in the UK in 2006 with the transfer of two Argentines, Carlos Tevez and Javier Mascherano from Brazil to West Ham United.

The economic rights of the two players were part-owned by a London fund, in a set up that was widespread in some European countries and South America at the time.

Then, such a set-up was not illegal in England, but there were important caveats that the investor could not attempt to influence club playing and selection decisions, or transfers, or indeed any other major club policy.

West Ham was fined £5.5m over the transfers of Carlos Tevez and Javier Mascherano.

However, it later transpired that a clause in the Tevez deal said that the third-party investor could move the player on to another club, and could decide the fee involved.

That broke Premier League rules, as it clearly "materially influenced" club policy.

West Ham admitted it was in breach of the rules, and was fined £5.5m for this and for hiding the details of the deal from the league.

The Premier League said TPO caused questions to be asked about "the integrity of competition" and also the impact it could have on the development of young players.

Because of the fallout from this case, and the issues it raised, the Football Association banned TPO at the beginning of the 2008-09 season.

The FA banned third-party ownership following the discovery that the economic rights of Argentina players Carlos Tevez and Javier Mascherano were owned by two offshore companies when they joined West Ham in 2006

Meanwhile, TPO was also described as a form of "slavery" by Michel Platini, the former president of European football's governing body Uefa.

But proponents of the system said it could enable cash-strapped clubs to acquire, and indeed sell, players.

In the South American countries of Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina TPO had been widespread.

That is because the production of new players for transfer to Europe has traditionally been the major source of income for clubs in South America.

With these clubs always searching for new talent to sell on, they often needed a third-party investor to help fund their own purchase of players and indeed their salaries.

As well as aiding the clubs, the investor could then make a healthy return on their investment if the player was sold on.

World football governing body Fifa says third-party ownership undermines the "overall integrity of the game"

However after growing concerns, in 2007 world football governing body Fifa set up a working group to examine the practice.

Its position now is that it believes "TPO has harmful effects on football and its essential values, thereby undermining the overall integrity of the game".

It took the decision in December 2014 to ban TPO, with the changes brought in during a transitional period in early 2015.

Four clubs; Santos of Brazil, Seville of Spain, club K St Truidense VV of Belgium, and FC Twente from the Netherlands, were all fined by Fifa earlier this year for breaching third-party ownership rules.

However, some player agents are believed to have found ways around the regulations.

These include buying shares in a club, and then taking a cut of any transfer fee that is subsequently received by the club for their player.

Another loophole is to ostensibly give a loan to a club and then not only be repaid that sum, but also to receive a type of interest payment, but again the sum is culled from any transfer fee achieved by the club selling on the player.

- Attribution

- Published27 September 2016