Globalisation: Where on the elephant are you?

- Published

The way in which wealth is distributed globally has changed dramatically in recent decades

There is, to use the great cliche, an elephant in the room.

The room is globalisation, the increasing international economic integration we have lived through over the last few decades.

The elephant is what that development has arguably done to the distribution of income.

Why an elephant?

Because there's a graph showing what has happened that looks like one (especially if you join the dots up carefully and add in some ears, eyes and legs).

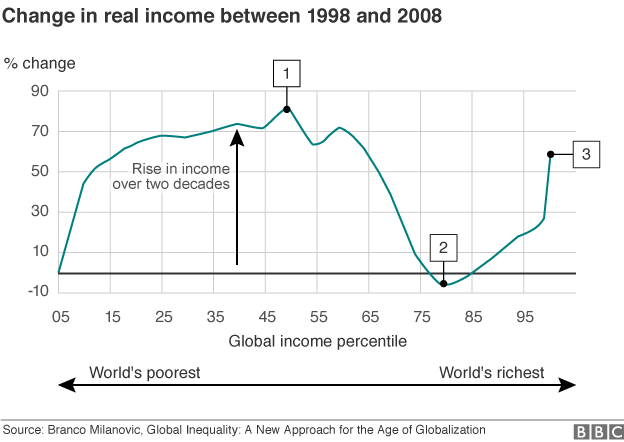

It shows what has happened to incomes across the global income distribution in the 20 years up to 2008.

Understanding the elephant

The horizontal axis shows the position in that distribution. The fifth dot, for example, is the 25th percentile. If you ranked everybody by income, that person would be a quarter of the way up the rankings.

The vertical axis shows the percentage change in income (in real terms, taking out inflation) in that part of the distribution between 1988 and 2008.

It is the work of a former World Bank economist, Branko Milanovic,, external and his colleague Christoph Lakner.

1. Middle classes in countries such as China, India and Brazil

2. Lower earners in countries such as the USA and UK

3. The richest individuals around the globe

What does it show?

Some of it is consistent with what is widely assumed to be the case. The very richest have gained a lot.

So have many round the middle of the range. That includes the growing middle classes in emerging economies such as China, India and Brazil. There are also some striking gains towards the lower end of the range.

But the very poorest got no better off at all.

And there is another group between the 75th and 90th percentile or so, where the gains appear to have been very small - and some of them appear to have actually lost out.

Who are they? Many of them are from the bottom half of the income range in the rich countries.

And that's why this graph has attracted so much attention. Perhaps these are the ones who have lost out because of globalisation.

Political significance

Branko Milanovic doubts, external we can really tell for sure.

"Establishing causality between such complex phenomena that are also affected by a host of other variables is very difficult and perhaps impossible," he cautions.

Still, he doesn't dismiss the idea and recognises the political significance.

"The temporal coincidence of the two developments and the plausible narratives linking them - whether made by economists or by politicians - make the correlation in many people's mind appear real."

Those "plausible narratives" include the idea that some workers have lost jobs or seen their incomes fail to rise because of low-wage competition in emerging economies, or at home in the shape of immigrant labour.

Many countries have seen a globalisation backlash and the rise of protest parties such as Italy's Five Star movement

We have certainly seen significant political developments that you could characterise as, in part, a backlash against globalisation and the increased flows of goods and workers across borders.

It was a factor in the British vote to leave the EU, the rise of anti-establishment political parties across Europe (Podemos in Spain, the Five Star movement in Italy and more) and in Donald Trump's criticism of American trade agreements in the US election campaign.

Of course, it's important not to forget the very large gains made by a substantial swathe of the population in the developing and emerging economies.

Globalisation has surely got a good deal to do with that, as jobs in exporting industries in China, for example, have helped to drive rising living standards.

Liberalisation brake

The perception that has gained strength in the rich world is that this improvement is driven by trade relations that are in some way unfair: workers in emerging economies are exploited, firms are subsidised, or that improved access to rich countries' markets is not adequately reciprocated.

That in turn underpins pressure on governments to rethink trade agreements and to impose new barriers to imports.

The World Trade Organization, external, for example, has found some evidence of an increase in new measures that restrict trade.

Governments are becoming more wary of new trade deals

But it is nothing like a massive upsurge in protectionism that reverses the trade liberalisation of the post-World War Two period.

Where the backlash is perhaps making more difference is in making governments more wary of new trade liberalisation agreements.

The EU and the US have run into major difficulties in the negotiations known as TTIP (the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership). Responding to popular concerns about the negotiations, senior European figures (including French President Francois Hollande) have poured a lot of cold water on TTIP.

It is not officially extinguished, but is under serious political pressure.

Another deal, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, has been agreed by governments, but not ratified by the US Congress, and has been disavowed by both the leading candidates in the presidential election.

One of them, Hillary Clinton, said when it was being negotiated that she hoped it would be the gold standard, but when the deal was done, she said it didn't live up to the "high bar" she had set.

Hillary Clinton says the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership did not meet her initial hopes

She said her position was consistent, but it could be that she was responding to the scepticism about trade deals of Bernie Sanders and now Donald Trump - respectively, her rivals for the Democratic nomination and for the presidency itself.

'Rising inequalities'

But there is a wrinkle to this interpretation. Has this group of less affluent people in the developed world done as badly as the data suggest?

A separate analysis by Adam Corlett of the Resolution Foundation, external of the data compiled by Prof Milanovic comes to a slightly different conclusion about what has happened to income distribution.

For one thing, there are more countries in the data for 2008 than for 1988. Faster population growth in emerging economies than in the rich world means that, for example, the group of people at the 75th percentile aren't necessarily the same in both 1988 and 2008.

And there are some important differences between the rich countries.

The weak results for this group, he says, are "driven by Japan (reflecting in part its two 'lost decades' of growth post-bubble, but primarily due to likely flawed data) and by Eastern European states (with large falls in incomes following the collapse of the Soviet Union after 1988)".

He concludes: "It would be hard to argue that the incomes of the developed world's lower middle class stagnated during this period, although the income growth of this part of the global income distribution still appears weak relative to other parts."

Some economists question whether less affluent people in the developed world really have done as badly as the "elephant graph" suggests

Still, relatively weak growth, especially when the people concerned can see that others have done much better, could feed resentment.

And there is no denying that the new political movements that have taken shape in some rich countries do partly reflect concerns that are about globalisation.

The last word goes to Prof Milanovic. "The political implications of a global 'elephant graph' are being played out in national political spaces," he says.

"In that space, rising national inequalities, despite being accompanied by lower global poverty and inequality, may turn out to be difficult to manage politically."

Find out more

On Thursday, 6 October the BBC will be reporting from around the world on the impact of globalisation on people's lives and on the growing movement against free trade.

There will be special coverage on TV, radio and online.