Heathrow expansion: How the cost of delays stacks up

- Published

The decision to build a third runway at Heathrow is just the latest chapter in a saga which has gone on for almost 50 years, ever since Harold Wilson's Labour government appointed the Roskill Commission to look at a third airport for London.

Cublington, Maplin Sands and "Boris Island" have all been considered and turned down, and instead the existing airports at Gatwick, Stansted, Luton - and Heathrow itself - have all been expanded.

However, the UK has built no new runways in the south-east of England since Gatwick's concrete runway was built in the late 1950s (though London City did open, albeit with a much shorter runway, in 1987).

Of course, even after today, things will not be finalised. Following the government's announcement of its preferred option there will be a public consultation process, before a final decision is made and put to MPs for a vote next year.

With Heathrow currently operating at 98% capacity - a much higher level than many of its rivals - many argue that this is affecting the UK's economy.

So what are the costs of this much-delayed decision, and how does the UK compare with other countries when it comes to airports?

What's the delay costing the UK?

Nobody knows exactly how much the years of delay may have cost the UK economy.

The Heathrow deal, in numbers...

Business groups like the Confederation of British Industry, the Institute of Directors, the British Chambers of Commerce and others - as well as the TUC - have all called for a third Heathrow runway to keep the UK competitive.

The CBI warned that repeated delays could cost the UK more than £30bn by 2030 - with the country losing out on trade to Germany and France.

This summer, a cross-party group of MPs, the British Infrastructure Group (BIG), external, said the delay in building a new runway at Heathrow was costing the British economy up to £6m a day in lost value.

They argued that following the UK's vote to leave the EU, the need for a new runway was even more pressing.

"Everyone acknowledges we need more airport capacity but indecision is costing the economy dear," said Grant Shapps, who chairs the group.

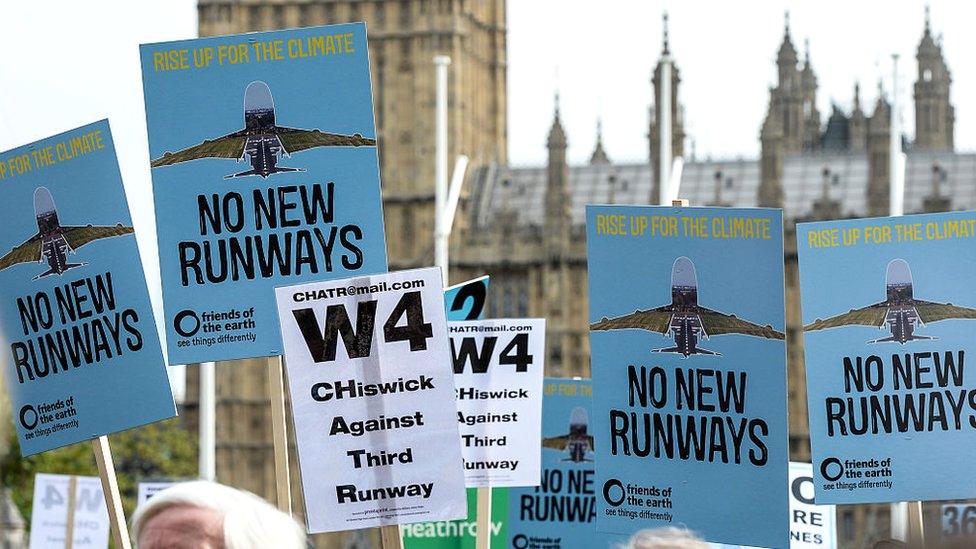

The decision to build a third runway will face continuing opposition

The MPs based their costings on figures from the government-appointed Davies Commission, which recommended building a new runway at Heathrow after nearly three years of deliberations.

The Davies Commission said this could provide a boost of up to £147bn to the UK economy over the next 60 years - the equivalent of about £6m a day.

However, this £6m-a-day figure is not so much a "cost" as an estimate of the opportunities the UK could lose out on if it doesn't have a runway - and a prediction of what these might be worth.

In its examination of the figures, the independent fact-checking charity, Full Fact,, external says it is "better to treat the estimates as judgements... with a reasonable degree of uncertainty, rather than facts".

Just looking at the economic costs and benefits of a new runway does not give you the whole picture

The Davies Commission itself says it is difficult to predict the impact of a new runway on the UK economy and has cautioned against attaching significant weight to the actual numbers.

Indeed the DfT has just said that a new runway at Heathrow will bring economic benefits to passengers and the wider economy worth up to £61bn over 60 years - which is less than half the Commission's figure.

But just looking at the net economic benefits won't tell you who wins and who loses - you also need to look at the social costs.

Passengers might enjoy cheaper travel and a better service, firms might be able to move goods and people in and out of the UK more easily - but those living close to Heathrow will face environmental costs and noise pollution, as well as public health concerns.

International expansion

In 1974, France opened Charles de Gaulle, Paris's new airport, while across the Channel the UK was still debating its options

Everywhere you look, it seems, somebody somewhere is building or extending an airport. While the UK has been in a holding pattern over a third runway at Heathrow, others have pushed ahead.

France has built Paris's Charles de Gaulle airport complete with four runways, Madrid and Frankfurt also have four runways apiece while the Netherlands has effortlessly added runways to Amsterdam Schiphol - it now has six.

The biggest expansion is being driven by the economic development of Africa and Asia - particularly China - and the accompanying growth in world passenger traffic. This has outperformed the growth in global GDP (except for a period between 2008-09) and is currently growing at 6.2%, says the European aerospace giant Airbus.

It reckons that between 2016 and 2035 global air traffic will grow at an average of 4.5% a year, external, with demand from countries like China outpacing growth in western Europe and North America.

The speed with which these projects have been conceived and implemented is breath-taking. For instance, Turkey's government only announced a third airport for Istanbul in 2013, but it is already about 30% built and is scheduled to open in 2018.

When all construction phases are finished in 2030 it will be one of the world's biggest airports, with six 3,750m runways and handling up to 200 million passengers a year.

By comparison, London's five airports currently handle 150 million passengers a year in total.

Istanbul's new airport will be one of the world's busiest when it is complete

China: Major airport programme

Last year, consultants KPMG said that the world's major cities would build 50 new runways by 2036 - a third of them in China alone.

"The emerging markets matter because within about a decade over half the growth in the world will come from these economies," says KPMG's James Stamp.

Yet China's own aviation authority has even more ambitious plans. The aim is to build 66 new airports in the next five years, taking the number of the country's airports to 272 from 206, the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) said earlier this year.

China is set to see the most significant increase in air travel in the next two decades

Air travellers in China took four billion domestic trips and over 100 million international trips last year, says the CAAC, which is also planning to increase the number of domestic and international routes.

The country is spending almost $12bn (£9.8bn) on civil aviation infrastructure this year, and is stepping up construction of important new airports, including those in Beijing, Chengdu, Qingdao, Xiamen and Dalian.

Work on Beijing's second international airport, at Daxing, the largest construction project in Chinese civil aviation history is well under way. Construction began at the end of 2014 and is due to be finished by 2019. It will have seven runways and be capable of taking 75 million passengers by 2025.

Meanwhile, a new runway is also being built at Beijing's existing airport that should help accommodate an additional eight million passengers a year - the airport handled almost 90 million passengers last year.

China plans to build 66 new airports by 2021, says the country's civil aviation authority

And yet, sometimes there is such a thing as having too many airports - even in China.

A lot of smaller airports are not doing well in attracting travellers - the most obvious example being Libo airport in south-west China, which was built at a cost of $57m but handled only 151 passengers in all of 2009, external.

Spain: 'Ghost airports'

In Spain in the boom years, many cities decided that what they needed was an airport, adopting the mantra of "build it and they will come". Sadly it hasn't worked. As the country's economy slowed, many of its regional airports closed.

Out of Spain's 46 publicly run airports, only a handful are now making money - and almost half are "ghost airports" with barely any passengers and empty terminals.

Ciudad Real airport, 235km (146 miles) south of Madrid, was meant to be an alternative to the capital's Barajas airport.

Ciudad Real airport is just one of a number of Spanish airports which are now virtually deserted

It cost €1.1bn ($1.19bn; £979m) to build, has one of the longest runways in Europe (4,100m) and could handle 10 million passengers a year.

But instead it lies deserted. The last scheduled flight was in 2011 and it closed in 2012 after just three years of operation. It was finally sold at auction this year for €56m, a fraction of what it cost to build.

Germany: Berlin debacle

And then there is Germany, a country often epitomised as the acme of trouble-free planning and efficiency. That's very definitely not the case with the capital's new airport.

Berlin Brandenburg Willy Brandt International Airport was designed to replace two existing airports. In 2004 it was optimistically estimated that it would cost €1.7bn and open in 2012; it is now years overdue and billions over budget.

The scandal-plagued project has seen changing designs, failures with its fire-control system, as well as high-profile resignations and sackings.

Berlin's new airport is billions over budget and years behind schedule

Fast-forward to 2016 and the total cost is now €5.4bn - and that could well rise to more than €7bn, some say. The opening date has now been pushed back to 2017 - and it could be delayed yet further.

"There is still a chance for us to open in the second half [of 2017]," Karsten Muehlenfeld, who was appointed the airport's boss in 2015, told the German newspaper Handelsblatt recently., external

"But... there are a lot of risks still in the building," he added. "We have a lot engineers who are working on that, but that doesn't mean you find a solution."

Dubai: World's busiest

Dubai is now the world's busiest international airport

Heathrow's most important rival comes not in Europe but in the Middle East, where Dubai has taken advantage of its location to become a major hub airport - overtaking Heathrow as the world's busiest international airport, external, and could soon become the busiest airport overall.

In addition to its existing airport - Dubai International - the emirate is also developing a purpose-built airport city 23 miles outside Dubai.

Al Maktoum International Airport will ultimately be able to handle 200 million passengers a year. So far it has mainly been used for freight.

The $30bn project is expected to be completed within six years, and is designed to handle up to 100 Airbus double-decker A380s simultaneously.

Is Dubai now best-placed to benefit from global air travel?

"Dubai is perfectly placed, being at the crossroads between east and west to take advantage of that growth [in air travel in Asia]," says Dubai Airports chief executive Paul Griffiths.

"There's a lot of airports in the world that won't be able to grow at the rates that they will need to grow to take advantage of that."

Perhaps the real challenge to Heathrow - and the UK, if you accept the importance of air travel to the economy - comes not from other airports but geography and changing patterns of global air travel.

Follow Tim Bowler on Twitter@timbowlerbbc, external

- Published22 October 2016

- Published17 October 2016

- Published10 October 2016

- Published20 July 2016

- Published30 June 2016

- Published25 October 2016

- Published1 July 2015

- Published30 June 2015