The untold story of the Texas-Mexico border

- Published

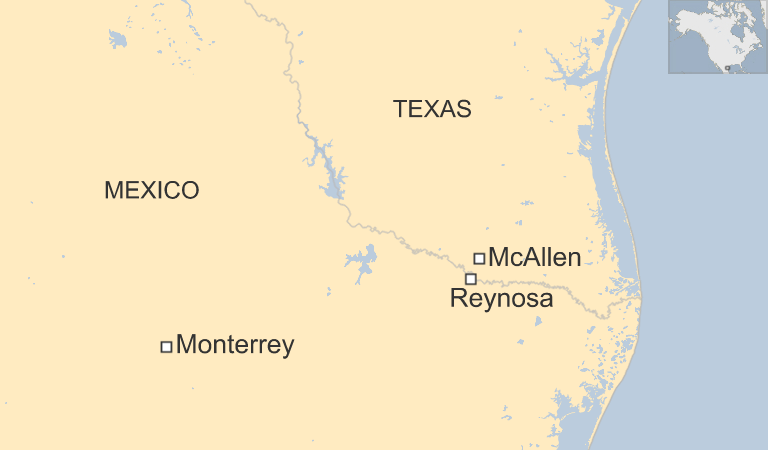

The Rio Grande river provides a natural border between Texas and Mexico

We weren't supposed to go to McAllen.

The small Texan city, not far from the border with Mexico, has a roadside shopping mall and an obligatory drive-thru Starbucks - but at first glance, not much else.

But Xochitl Mora was insistent. We were not to leave the Rio Grande Valley until we had come to see for ourselves. In McAllen, she assured us, we would see another side to the immigration debate that has been a fixture of this election cycle.

Ms Mora works for McAllen's mayor, Jim Darling, a Vietnam veteran who headed down south after the war, because he couldn't stand the cold winters in his native New York.

The majority of those arriving in McAllen are women and children, fleeing gang violence in Central America

For decades, the easygoing politician - who arrived late to our meeting at City Hall, out of breath and apologising for not wearing a tie - enjoyed the relative serenity of life in Hidalgo County.

Then, roughly two years ago, the peace and quiet in McAllen were disrupted.

"The first day I knew something was happening," he recalls, in his adopted Texan drawl, "I was down at the bridge, and the port director said, 'We had 15 kids yesterday.' We're not used to dealing with kids.

"Within two days, there was a situation."

After being processed by US border control, many migrants are dropped off at McAllen's small bus station

The "situation", which Mayor Darling refuses to call a crisis, was a sudden influx in the number of women and often unaccompanied children fleeing El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras - the infamous Northern Triangle where lawlessness, extreme poverty and gang violence are rampant.

"Some swim across the Rio Grande river," says Josh Ramirez, McAllen's director for health, "some just walk across the bridge to a checkpoint, and say, 'I'm here.'"

Listen to Joe Miller's report from the Texas-Mexico border on Business Daily

They've survived a journey which many never complete, and on which physical and sexual violence is commonplace.

After being processed by the US border patrol, and undergoing the requisite security checks, the migrants are dropped off at the local bus station. The hope is that they will somehow find their way to relatives elsewhere in the US, and await a court hearing.

At first, 30 or 40 arrived in McAllen each day. But over the last two years, at least 44,000 have come through the city, whose population is only 140,000 - and the number keeps rising.

Children often arrive in McAllen suffering from malnutrition and dehydration, after enduring the arduous journey across Mexico

In recent weeks, 200 women and children have arrived before lunch every day.

This surge has put a strain on the city's health services and municipal resources, and landed local authorities with a bill of more than $300,000 (£250,000).

But public attitudes to the porous border remain largely positive, for McAllen, once "a dusty little border town", has thrived off cross-border trade, boosted by the now politically out-of-favour North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta).

"We're the largest per capita sales tax collector in the state of Texas," Mayor Darling explains, "because 38% comes from Mexico."

Occasionally, anti-immigration protesters assemble outside the McAllen bus station, where the migrants are dropped off

The well-off drive from Monterrey to shop in McAllen's large mall, and the city operates much of the supply side for the maquilas, or manufacturing factories, based a few miles away in Tamaulipas.

The likes of Panasonic, Sony and LG employ hundreds of thousands in Reynosa, and McAllen gets the corresponding logistics, warehousing, and corporate offices, including a Japanese chamber of commerce.

The two cities' fortunes are so intertwined that McAllen spends roughly $1.5m a year in economic development - mostly in Mexico.

Which may account for the warm welcome central American migrants who come through McAllen receive from local residents and volunteers, including Sister Norma Pimentel, of the local Sacred Heart Catholic Church.

The repurposed church hall now resembles a Wal-mart shop floor. Dozens of tables are piled high with shoes and clothing donated by locals - and ordered by size and age, in Spanish. Jeans for ninas, aged 7-10, t-shirts for ninos, aged 10-14.

The local border patrol often apprehend unaccompanied minors, who have been dropped off at the US border

In another part of the room, sanitary pads, maternity clothing and nursing bras are provided, along with baby formula and basic medical supplies for those suffering dehydration, malnutrition or worse.

This respite centre, says Sister Norma, whose devotion to the migrants' cause led to a Skype call from Pope Francis, "is where we restore their human dignity".

In an air-conditioned tent in the church's car park, the morning's arrivals rest, after enjoying their first shower, and possibly their first proper meal, in weeks. Some phone their loved ones to assure them that they are, at long last, safe.

At least a dozen young boys and girls lie on camp beds; in the corner, a 17-day-old baby, whose mother had hoped to give birth in America, but ended up having the child just a few miles from the border.

Local volunteers in McAllen provide food and clothing to migrants at the local Catholic church

Alexander, one of the few men to come through the centre, talks of his journey across Mexico with his young son, in which they stood for days in a trailer tractor, with no toilet facilities. He paid $4,000 to a coyote, or people smuggler, in Honduras, and as soon as his son gets settled in the US, he says he'll head back to get his wife and other children.

Most of the others are tight-lipped. But one woman, when asked about whether a new occupant of the White House could mean a crackdown on illegal immigration, is defiant. "If they deport me and my kids tomorrow," she says, "I'll make the trip again, because there is nothing there for us."

Sister Norma and her army of volunteers treat the McAllen "situation" as primarily a humanitarian crisis, but for Mayor Darling, it's a political headache.

Shortly after the town was faced with the first wave of women and children, the mayor went to Washington and applied for emergency federal funding "as if it was a hurricane".

Almost half of those apprehended in the Rio Grande Valley turn themselves in voluntarily

When a cheque for a few hundred thousand dollars was finally made out, it was processed by the state of Texas, whose Republican administration has not been overly inclined to deal with illegal immigrants in the Democrat-voting border region, and only $8 made it to McAllen.

Neither the Clinton nor the Trump campaign has visited McAllen, nor have many mainstream media outlets. When politicians do come down, much to Mayor Darling's chagrin, "they drop in for a photo-op and a press release", and head back in helicopters.

But to those elsewhere in the United States wondering why they should care about the daily struggles of a dusty old town at the very bottom of the country, the ever-sanguine mayor has a simple warning.

The border patrol, he says, is preoccupied with processing these desperate women and children, but "the drugs and all that is just passing through us and it's coming to a neighbourhood near you".

Follow Joe Miller on Twitter @JoeMillerJr, external

- Published17 March 2016