Has the hand-written signature had its day?

- Published

Will written signatures become purely ceremonial in the digital age?

When President Obama signed the nattily named Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010, it marked the most significant regulatory overhaul of the US healthcare system since 1965.

Fittingly, he used 22 different pens to sign the document - now more nattily nicknamed "Obamacare".

It continued a long-held American tradition that sees the pens used to sign historic documents donated as thank-you gifts. The more pens used, the more gifts can be made.

President Lyndon Johnson reportedly used more than 75 pens to sign the landmark Civil Rights Act in 1964. One, an Esterbrook, was given to Martin Luther King Jr.

And these pens can give us a tangible slice of history.

President Obama used 22 pens to sign his Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010

For example, the Parker Duofold Big Red used by General Douglas MacArthur to sign a surrender document aboard USS Missouri - effectively signalling the end of the Second World War - is now proudly displayed at the Cheshire Military Museum in Chester.

But is this where ink pens and hand-written signatures now belong - in museums?

On 1 July 2016, the European Union implemented new rules for electronic signatures, giving them the same legal weight as their "wet" - or ink-based - written counterparts.

The new eIDAS (European Identity and Trust Services) regulation has effectively put an end to a confusing patchwork of laws, making them consistent across every EU country.

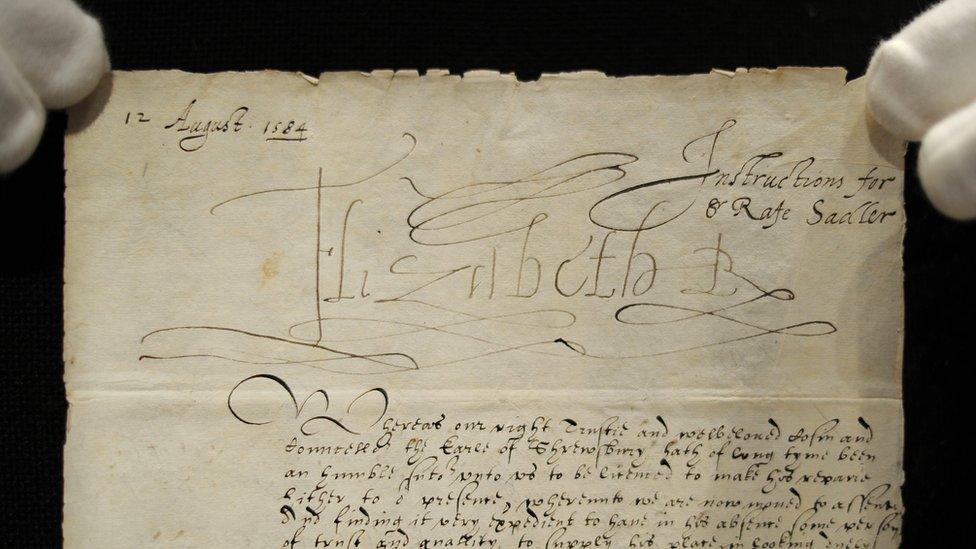

Queen Elizabeth I of England had a flowery signature that projected power and authority

So why has it taken so long? After all, the idea of a digital signature or certificate that proves you are who you say you are has been around for many years.

Businesses have been slow to adopt electronic signatures because "until now, there has been no legal framework or regulation which properly defines them," argues Mark Greenaway, director of digital media at software firm Adobe.

Such confusion has fuelled scepticism.

"The technology has been around for a while, but adoption in the UK is now commencing because people are starting to believe in it," says Richard Croft, chief communications officer at software company Legalesign.

Who are you?

The inability to prove online identity and authenticate documents has always been something of an Achilles heel for the internet.

But a number of different technologies have emerged to tackle this.

In Estonia, for example, every resident over the age of 15 has an ID card protected by a personal identification number and containing a digital signature. This enables them to access government services, digitally sign documents, and vote electronically in parliamentary elections.

Estonians have had digital ID cards since 2002, and about 1.2 million people use them

They can do this on their smartphones, too. Around 170,000 people voted digitally last year.

"I'd rather not spend precious time on administration," says Anna Piperal, managing director of e-Estonia Showroom at Enterprise Estonia. "There is no value in that."

But even without paper to shuffle and ink to dry, such pragmatism doesn't mean the end of face-to-face communication.

"We still like to meet and talk, discuss, but not sign papers in stacks and spend a fortune printing and scanning," she says.

It is little wonder that 2% of Estonia's GDP [gross domestic product] is saved every year as a result of digital signatures.

We can now sign contracts digitally using services such as Legalesign

"It makes business administration easy," she says. "For example, you can start a company in just 18 minutes."

And Legalesign has just launched an online witness product, enabling business people to sign contracts by typing their name, signing with a mouse or uploading their signature.

The signature is made in the presence of a witness, and the ID of the signatory is verified over email. The final document is tamper-proofed using an encrypted digital certificate.

'Weak evidence'

The problem with written signatures - even those signed with a beautiful pen and a practised flourish - is that they can be forged.

"A [written] signature is simply weak evidence that somebody agreed to do something," says Jon Geater, chief technology officer at Thales e-security.

"It is not exactly unique or special, nor does it prove particularly well that a person was genuinely present or consenting."

Digital counterparts, on the other hand, whether using blockchain technology, which relies on a consensus agreement before verifying a signature, or password-based digital signatures, do away with this uncertainty.

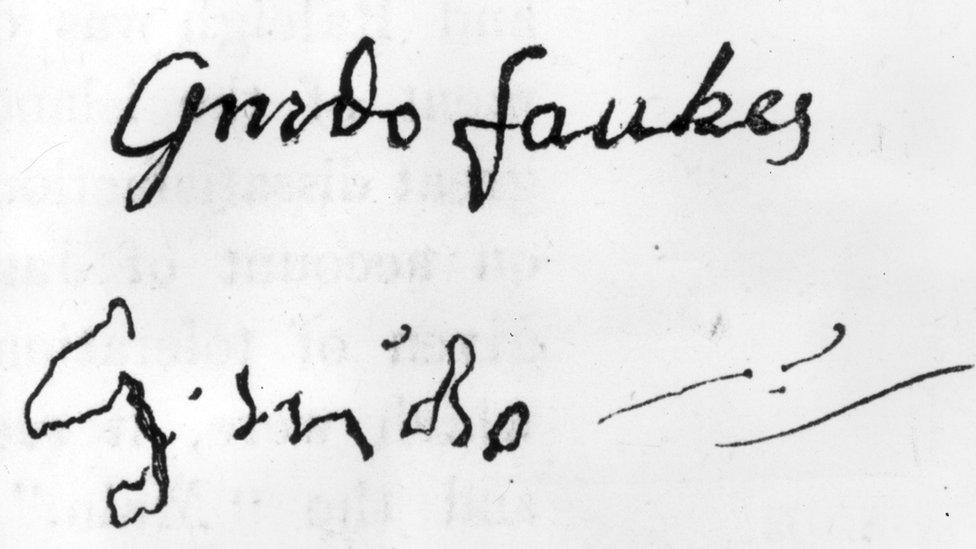

Unreliable: The autographs of Gunpowder Plot member Guido Fawkes before and after torture

"Modern digital technology provides considerably greater assurance that a piece of information was genuinely approved or agreed," says Mr Geater.

This enables business relationships to be "described, enforced and verified without the unnecessary involvement of superfluous middlemen, and with much greater levels of proof," he says.

Ron Hirson, chief product officer at US-based tech firm DocuSign, agrees, saying: "The benefits of digital business are outweighing the nostalgia of the hand-written signature."

Signing ceremony

But while describing written signatures unstintingly as "extremely primitive", Mr Croft does accept that digital versions lack theatre.

"Viewing the Magna Carta, external in person holds a certain magic. In a couple of generations time, the idea of inspecting a certified digital copy of the Great Repeal Bill signed with Her Majesty's encryption code might not be the same crowd-puller," he admits.

And some of the world's biggest businesses rely on the ritual of putting pen to paper to please the crowd.

Would the Magna Carta signed by King John in 1215 be as interesting with a digital signature?

"Take Zlatan Ibrahimovic signing for Manchester United this summer," says Dr John Curran, a business anthropologist and founder of research firm JC Innovation and Strategy.

"It goes way beyond the signing of a lucrative contract. The ceremonial nature enables the club, as a brand, to display its intent for success, whereas for the fans, it satisfies their need that their team is developing."

And we certainly don't seem to be losing our love of pens. In the US, traditional pen retail sales were up 4% in 2016 compared with 2015, according to the NPD Group.

Could you afford to buy Caran D'Ache's Astrograph luxury pen?

"People still want that status or 'lifestyle piece' for important and meaningful signatures, like buying a house," says NPD analyst Leen Nsouli.

That said, you might think twice before buying the latest luxury piece from Swiss company Caran d'Ache, which recently collaborated with watch and timepiece brand MB&F to create its limited edition Astrograph pen.

It contains 99 components and is a snip at just under £20,000.