The proven health trackers saving thousands of lives

- Published

Heart disease and strokes kill around 14 million people a year worldwide

It was when Vic Gundotra's father suffered serious heart problems and nearly died that the former Google executive decided to move into healthcare tech.

He now runs a firm called AliveCor that has developed a heart-monitoring device causing excitement in medical circles.

AliveCor's recently launched Kardia Band, which integrates with Apple's smart watch, takes an electrocardiogram (ECG) of your heart, measuring its electrical activity as it pumps away.

Medical experts believe it could potentially save thousands of lives.

It can spot atrial fibrillation (AF) - one of the most common forms of abnormal heart rhythm and a major cause of stroke.

You place your thumb on the metal sensor in the watchband to complete an electrical circuit and it can take a reading in 30 seconds, sending the data to the watch over high-frequency audio rather than Bluetooth or wi-fi.

AliveCor's Kardia Band version of the heart monitor links to Apple's smart watch

Kardia Band can spot other problems, too, but currently only has regulatory approval for AF. If it spots anything else unusual it suggests you go and see your doctor.

"The problem with atrial fibrillation is that it's asymptomatic, which means it can come and go and often isn't diagnosed," says Mr Gundotra.

For example, Ron Grant, 70, told the BBC: "At the age of 55, I had a massive heart attack - flatlined - had a bypass. It was some years after that we discovered I had AF - a funny heart rhythm to put it simply - which could lead to stroke".

Mr Grant now uses the smartphone compatible version of the AliveCor device to keep tabs on his ticker.

"People start modifying their behaviour once they begin monitoring their own health," says Mr Gundotra.

"No-one's more interested in heart health than the owner of the heart."

Biggest killers

Heart disease and stroke are the biggest killers in the world, accounting for about 14 million deaths a year.

If technology can give us a warning that things are going wrong before it's too late, many lives could be saved. And health budgets could be applied more effectively elsewhere.

In the US, around 130,000 people die a year directly or indirectly from AF, while more than 750,000 have to go to hospital, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

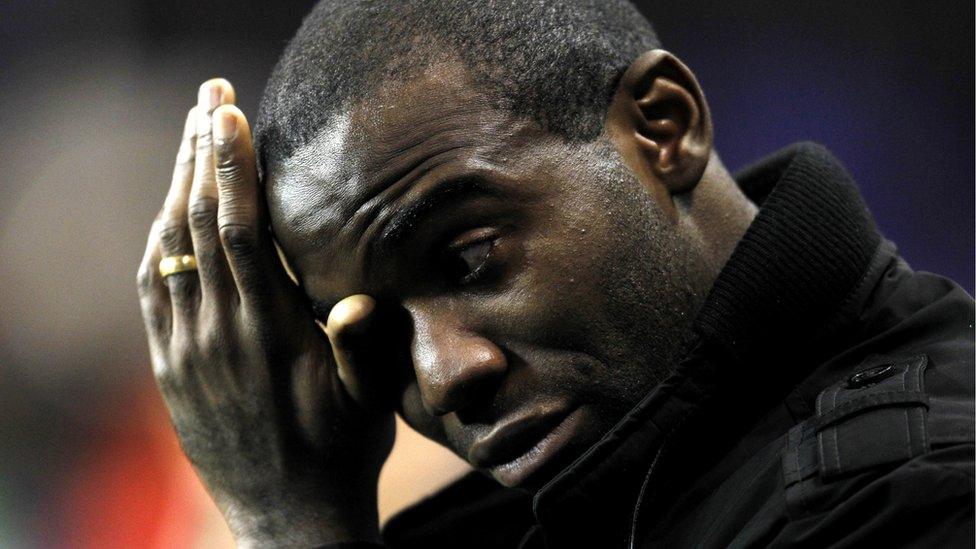

Former Bolton Wanderers footballer Fabrice Muamba survived a cardiac arrest during a game

And it costs about $6bn (£4.8bn) a year to treat the condition in the US.

In the UK, around 100,000 people suffer sudden cardiac death each year, to which AF is a contributor.

According to NHS England, AF is responsible for a third of all strokes and costs the NHS more than £2.2bn a year to treat.

So it's easy to see why health authorities are interested in simple wearable devices that could significantly increase early diagnosis of such heart problems before they become life-threatening - and more costly to treat.

In the summer, Simon Stevens, head of NHS England, said such innovations would be "fast-tracked" so they can be adopted within the English health system much more quickly.

Clinically proven

There are scores of fitness trackers on the market these days, most of them wristbands, and while they may be useful motivational tools, most of them don't yet have regulatory approval.

"Fitness trackers are all very well, but doctors want clinically proven products whose data they can use to make clinical decisions," says Mr Gundotra.

But going through the rigorous testing process required for a health product to receive regulatory approval can take years, so it's no wonder most consumer tech companies don't bother.

AliveCor's smartphone compatible heart monitor, Kardia Mobile, has regulatory approval

Confusingly, AliveCor's smartphone compatible sensor, Kardia Mobile, has received regulatory approval in the US and Europe, whereas the Kardia Band smart watch version is currently approved only for Europe.

"We hope to get US approval soon," says Mr Gundotra.

Collating and studying millions of ECGs AliveCor's sensors have taken, and applying machine learning to the data, is also promising to reap rewards - although these are early days for the research.

The software interprets the electrical pattern your heart makes, looking for abnormalities

AliveCor is collaborating with the Mayo Clinic in the US to see if other useful indicators can be discerned from the electrical pulse patterns generated by our hearts.

For example, they may be able to detect whether you have too much or too little potassium in your system, a mineral that plays a key role in keeping your heart beating in a normal rhythm.

Potassium also helps your nerves to function, your muscles to work, and your kidneys to filter blood. At the moment we can only find out potassium levels from a blood test, so if this information could be gleaned from a quick ECG instead, the medical benefits could be huge.

Wearables that work

So what other clinically proven apps and gadgets are causing a stir?

Remote monitoring is a big area of research, with companies like Preventice Solutions and Biotricity offering heart monitoring kit that records and sends ECG data wirelessly to a smartphone app or to the cloud, allowing doctors to be alerted immediately of any heart abnormalities in their patients.

Preventice's BodyGuardian has received approval by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), but just the software element of Biotricity's Bioflux product has so far been approved.

Dexcom's blood sugar monitor sends data wirelessly to a smartphone

"Remote monitoring could save a lot of money - hundreds of thousands of dollars a year - because people have to go into hospital much less often," says Annette Zimmermann, research director at Gartner.

And Dexcom has recently had its continuous glucose monitoring system approved by the FDA, enabling people with Type 1 or 2 diabetes to measure their blood sugar levels automatically every five minutes and see the trends displayed on a smartphone.

A growing number of advice apps are winning approval, too, from myCOPD, which enables patients to manage Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder (COPD), to BlueStar, an app helping people with Type 2 diabetes manage their condition.

Fitness wearables may be more fashionable, but it's the clinically proven gadgets and apps that could end up saving the most lives.