Tata crisis: How do you sack a boss who won't go?

- Published

Tata Group wants to remove Cyrus Mistry from all its companies

Imagine you work for a company that has been engulfed in a bitter power struggle for weeks.

Your chairman was unceremoniously sacked. The management feud has divided directors.

Meanwhile your customers just don't know what to think.

And to cap it all off, despite the spat being played out in the world's media with a to-and-fro of insult and insinuation, the dumped boss is still very much part of the company.

Sounds pretty horrendous, but that's the reality for 660,000 staff employed by India's Tata Group.

It is the country's largest conglomerate, with stakes in more than 100 independent companies, many of which bear the Tata brand.

And still at the helm or on the board of some of the most high-profile Tata businesses is Cyrus Mistry, the ousted chairman.

'Tarnished' reputation

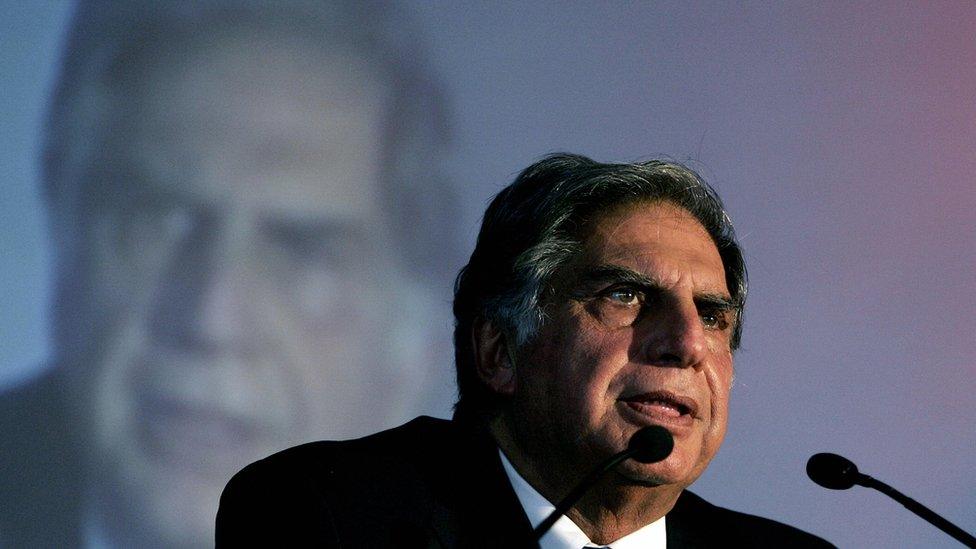

The saga, which saw Mr Mistry unexpectedly replaced by his predecessor and company patriarch Ratan Tata, has been a sorry chapter in a usually proud 148-year history of the Tata Group.

So with the fallout of this ugly public ousting still swirling, how do you go to work each day, keeping your chin up and your head down?

Not easily, some say.

Ratan Tata is standing in for now but is on the hunt for a new chairman

"There's a great sense of pride in being a staff member of a Tata company and that follows from the ethical standards that the senior leaders have held themselves to," says Prof Kulwant Singh from the NUS Business School in Singapore.

"All these events have tarnished Tata's reputation and that must affect morale and belief in the Tata Group."

And while it is human instinct to pick sides, that is difficult for employees - not least because it's not entirely clear yet who'll come out on top.

"The staff are caught in the middle and they're watching how this plays out but they won't want to interfere," says Nitish Jain, president of the SP Jain School of Management.

"I think it's obvious that the staff are quite rattled, they want clarity sooner rather than later but they have no choice but to be patient."

Not straightforward

Patience will be crucial.

Wrestling control away from Cyrus Mistry may not be so straightforward. His family has been a major investor since the 1930s, and controls companies holding 18% of Tata Sons. And crucially Mr Mistry still has plenty of support.

That explains why, despite everything that has gone on, he is still chairman of Tata Chemicals as well as Indian Hotels, owner of the world famous Taj brand.

Tata Motors directors can't decide whether to axe Cyrus Mistry

Tata Group may own a stake in each of those businesses, but they are separate legal entities, meaning Mr Mistry can only be removed by each company's board.

That's exactly what happened at Tata Global Beverages, for example, the business that runs the Starbucks franchise in India where he was chairman, and at another huge operation Tata Consultancy Services.

But directors at Tata Steel and Tata Motors still can't decide whether to carry out the wishes from Tata headquarters and cut ties.

"There appear to be factions that have emerged within the boards of Tata companies," says Prof Singh.

"At least some of these board members seem somewhat reluctant to follow through on Tata Sons' attempt to oust him."

Under Indian law, Mr Mistry can attend shareholder meetings of any Tata company while he remains a board member of that company. He can also attend those meetings on behalf of a shareholder.

Brand bargaining

Showing too much loyalty to Mr Mistry could be a dangerous game.

For each of these businesses, the Tata brand is vital. Being able to use that famous name often helps win customers and, when they need it, get financing too.

Cyrus Mistry and Ratan Tata in better times - a meeting with then-Gujarat State Minister, Narendra Modi, in December 2011

And so Tata Sons - with its power to take away permission to use the Tata name - could hold a trump card, believes Prof Singh.

"This access to the Tata brand is critical to these companies, so they are likely to comply with the overall wishes of the Tata Group," he says.

With the risk of more damage to morale, reputation and productivity, Prof Singh predicts a resolution soon, especially with Ratan Tata on the hunt for Mr Mistry's permanent replacement.

"I don't see this dragging out for months," says Prof Singh.

"I believe the Tata Group board will want to hand over a settled company to the new chief executive and will therefore try to resolve all of these issues relatively quickly."

You get the impression though that Cyrus Mistry will make this as difficult as possible.

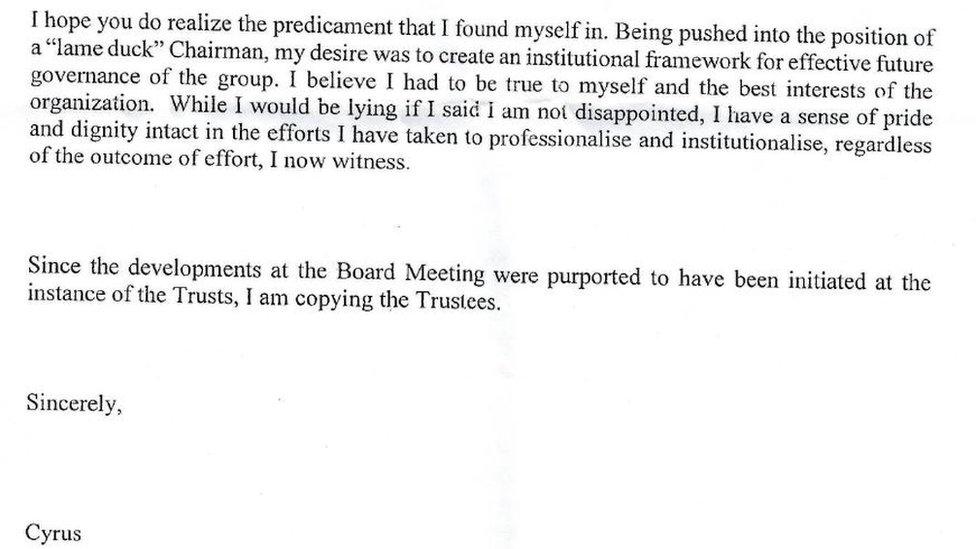

This is someone whose opening salvo was a no-holds-barred nine-page email slamming the Tata business that was leaked to the media.

Cyrus Mistry's now-famous "lame duck" email

"If he just exits without putting up a show, his colleagues may consider him too weak. If he puts up a show they might think he's too much of a fighter," says Mr Jain.

"But if he represents his case as he's doing currently, he may negotiate better terms than a lame duck exit, which is what he'd be doing if he just gave up now."

'Against the Tata way'

For Prof Singh, the fact that Tata is in this predicament at all seems unnecessary.

"I wonder why they didn't come to an agreement that would have given him a graceful exit to avoid this public humiliation.

"That would have been much smoother because this really is against the Tata way."

Of course it takes two parties to agree, and who knows if they had tried to achieve an amicable split but failed.

But even if Tata eventually manages to oust Cyrus Mistry from all its companies, the group may never be able to silence him.

- Published11 November 2016

- Published10 November 2016

- Published26 October 2016

- Published27 October 2016