Should US banks do more to prevent a banking crisis?

- Published

Donald Trump's victory has boosted share prices on Wall Street

Shares in US banks have surged since Donald Trump won the US election. It is in expectation of the president-elect's proposed bonfire of what he believes are rules and regulations that hamper business.

But in banking, many of those rules were put in place after the last financial crisis in the hope of preventing a future meltdown.

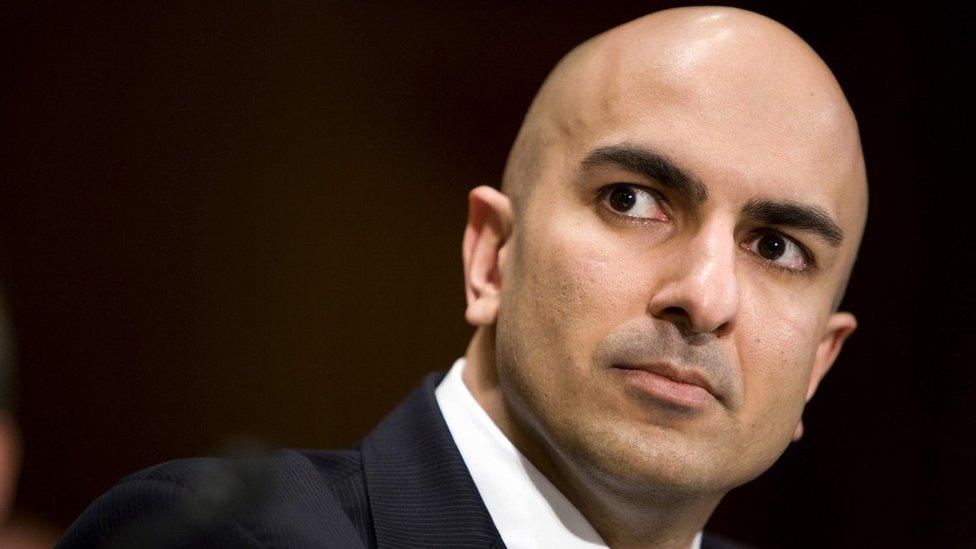

Now Neel Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis is proposing an alternative that may be more in line with Donald Trump's way of thinking.

He believes that banks should be forced to massively increase their capital reserves - the amount of cash they are obliged to keep in hand for the day when everything goes wrong at once.

Boosting reserves

Currently, US banks need to keep 6% of what are known as their risk-weighted assets, a formula that values their their loan book, in cash. Under the so-called "Minneapolis Plan", Mr Kashkari wants banks to significantly increase this ratio to up to 38%.

Neel Kashkari says measures to prevent another bank meltdown don't go far enough

"My highest focus is making sure we don't have another financial crisis where the banks get into trouble and they have to turn to the taxpayers," he told BBC World Service.

"We've looked at the history of financial crises - this is like trying to predict earthquakes or hurricanes, they don't happen very often.

"And if you look at financial crises all around the world, that's the level of capital that we need to reduce the chance of a future crisis to as low as 10% over the next century."

Under President Obama, the United States introduced the Dodd-Frank Act in an effort to tame Wall Street in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

However, Mr Kashkari says it does not go far enough in preventing another banking meltdown.

"Before the last crisis, there was around an 84% chance of a crisis. With Dodd-Frank, that's been reduced to 67%, but that's still far too high in my opinion", he says.

Despite changes following the 2008 crisis "the biggest banks are still too big to fail", says Mr Kashkari

"That's why we've come up with this plan. Some banks we think will restructure themselves to become smaller and less risky to avoid these high capital requirements," says Mr Kashkari.

"Right now we have a system where the biggest banks are still too big to fail.

"The IMF and other regulators have estimated that the cost of a financial crisis is around 160% of GDP, which for the US economy is $28trn. That cost is born by main street - not by the bankers."

Financial implications

What is Wall Street likely to make of this proposals? Currently there are around 8,000 banks in the United States, and just six of them hold 90% of all deposits.

The Federal Reserve currently requires US banks to hold 6% of their assets in cash

Chris Lowe of FTN Financial says it's not necessarily a bad idea, but the key to success would be the plan for transition.

"If it were done in one fell swoop it would have massive implications. Finance is one of the country's biggest industries. JP Morgan with a 38% capital ratio couldn't compete with BNP Paribas and Deutsche Bank.

"So would you try to do this just in the United States; or do you try to get all international banks to take part, too?

"Presumably also it would be harder to get a business loan, harder to get a mortgage, or to get a corporate or municipal balance sheet underwritten - which means there would be a broad economic impact."

If Mr Kashkari's proposals were implemented, there would be an economic impact, say some

But other finance industry watchers are more enthusiastic.

Prof Roger Farmer of UCLA in California says Mr Kashkari's proposals may not even go far enough, and that the only real answer is much tighter regulation.

"What happened in the deregulation of the 1990s was the development of new institutions - people have called it shadow banking.

"The shadow banks were not regulated, and on top of that firewalls were removed between investment banking and retail banking," he says.

"But even if those firewalls had not been removed, new institutions were developed that were doing things that were similar to banking that I personally believe would still have led to financial crises."