Is Cadbury's move the end for Fairtrade?

- Published

Cadbury is to replace its Fairtrade certification with an in-house scheme

News that the UK's best known chocolate brand, Cadbury, is abandoning its Fairtrade certification has caused some concern in the food industry.

Parent company Mondelez says it plans to bring all Cadbury lines under its existing in-house fair trade scheme, Cocoa Life.

As a result, it says it will offer five times more sustainable chocolate in the UK, external by 2019.

But critics warn this could confuse consumers.

They also fear that shared standards around ethical trade will be lost if more firms drop Fairtrade.

So what prompted Mondelez's change of approach, and does it leave the future of the Fairtrade mark in doubt?

Mondelez's change of approach

Broadly, Fairtrade works as a voluntary certification system which holds adherents to strict standards - in particular paying a minimum price for raw materials such as cocoa, sugar and coffee.

But Glenn Caton, northern Europe president at Mondelez, tells the BBC that while his firm and Fairtrade have the same goals, "sustainability is about much more to us than price".

"The next generation of farmers aren't taking on cocoa farming like they used to because it is so unprofitable, so we have to make sure their communities thrive and this means investing more in their communities," he says.

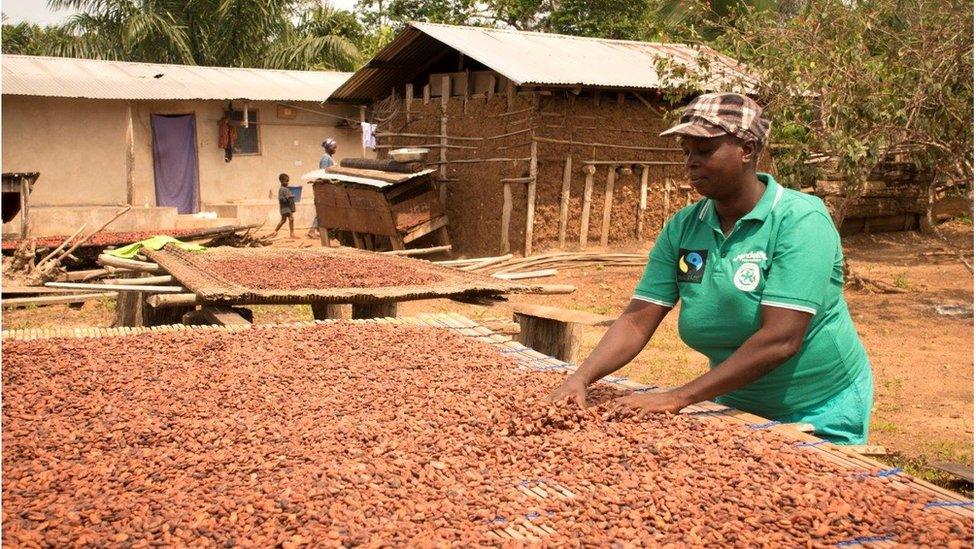

Mondelez's Cocoa Life scheme aims to invest more in cocoa-producing communities

As such, Mondelez wants to lead its own sustainability efforts - investing more in areas such as its supply chain, bonuses for farmers, training and climate change prevention.

The Fairtrade Foundation has welcomed the move, too, which it says will leave farmers in developing countries like Ghana at least as well off, if not better-off.

"The relationship is not ending, it's changing," says policy and public affairs director Barbara Crowther, pointing out that the Fairtrade Foundation will remain a partner to Cocoa Life - independently assessing its progress and reporting its findings.

Fairtrade exodus?

The big question now is whether other firms will also choose to abandon Fairtrade certification and adopt their own systems of self-regulation.

Certainly criticism of the Fairtrade system is mounting in the cocoa industry, says Dr Steve Davies of the Institute of Economic Affairs.

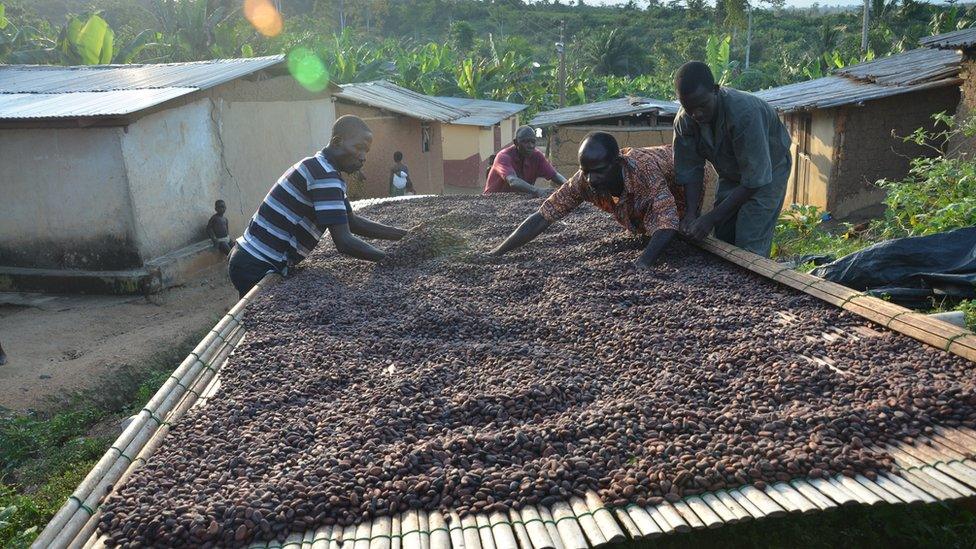

The next generation is not taking on cocoa "because it is so unprofitable", say Mondelez's Glenn Caton

The big issue is that most cocoa producers are small farmers who can't achieve the economies of scale of bigger farms, and that leaves many vulnerable to risks like drought and struggling to survive.

"Fairtrade does bring benefits to some producers, but it will not be a way of transforming the world trade system as some people seem to see it," he says.

"The only way to improve conditions for people working at bottom of the supply chain - those farming raw materials like cocoa - is by investing in the supply chain. Price floors might help but will only go so far."

Complex systems

Another issue, says Tobias Webb, of supply chain consultancy the Innovation Forum, is that firms can find the web of overlapping ethical trade certifications out there complex to manage.

These include not just Fairtrade's, but the Rainforest Alliance - which is dedicated to the conservation of tropical forests - and UTZ, the world's most prevalent label for sustainable farming.

"Producers can end up putting four or five labels on their products, and achieving each one requires a costly and time consuming audit.

Many small farmers struggle to produce cocoa profitably

"So many businesses like Mondelez are now moving towards in-house systems where they work in partnership with the NGOs as independent observers.

But not everyone wants to see Fairtrade stepping back from its role as a leading promoter of ethical trade.

Anna Taylor, executive director of think-tank the Food Foundation, says the UK has seen a "rapid rise" in Fairtrade sales in the last two decades which has been of huge benefit to farmers in the developing world.

Fairtrade cocoa products by volume increased 6% in the UK in 2015, and around 4,500 products in 74 countries have the Fairtrade mark worldwide.

'Black-box supply chains'

The risk, she adds, is that we could lose a transparent set of universal standards that consumers "trust, see and recognise".

"Consumers more than ever want to be able to trust where their food comes from and are worried about 'black-box' supply chains."

Mr Webb sees another potential risk in big firms pulling away from the Fairtrade system.

Mondelez and Fairtrade will continue to work together to improve conditions on cocoa farms

"Will NGOs still be able to resource themselves to play the role of the critical friend? There is potentially a risk there that there is no independent observer - but firms do understand they need that credibility."

Ms Crowther says the Fairtrade Foundation does not see Mondelez's move as a threat to its future, and welcomes companies "taking ownership" of their sustainability challenges.

She adds that her organisation is also evolving to meet the cocoa industry's changing needs and moving beyond its historical focus on price regulation.

"If there is an opportunity to innovate in different way then we welcome it. It's also worth mentioning that Mondelez will continue to source the same amount of Fairtrade-certified sugar for its products.

"We are still the most recognisable ethical-trade mark globally and that's not going to change," she adds.