Breaking the mental health taboo: 'Please talk about it'

- Published

Sam Brown says she's now more disciplined about taking breaks from the 'perform, perform, perform' culture of work

There's a frequently quoted statistic that one in four of us will suffer a mental health problem at some point during our life. But what does it mean to be that person, especially in the workplace?

Early last year, Sam Brown, a partner in the law firm Herbert Smith Freehills suffered what she calls a "professional breakdown". It started with her becoming very tired and stressed and despite her efforts to overcome those feelings, she says they just got worse.

"It came to the point where I couldn't really concentrate. I couldn't sleep properly and I started to be fearful about my work, that it wasn't going to finish, there was too much and I couldn't get a grip on it," she explains.

Eventually Sam went "kicking and screaming" to a psychiatrist and was signed off from work for three months. She admits that even though she rested during that time she didn't get her head round what had caused her failure to cope.

She returned to work, but suffered a second breakdown and spent two weeks in hospital before she recovered.

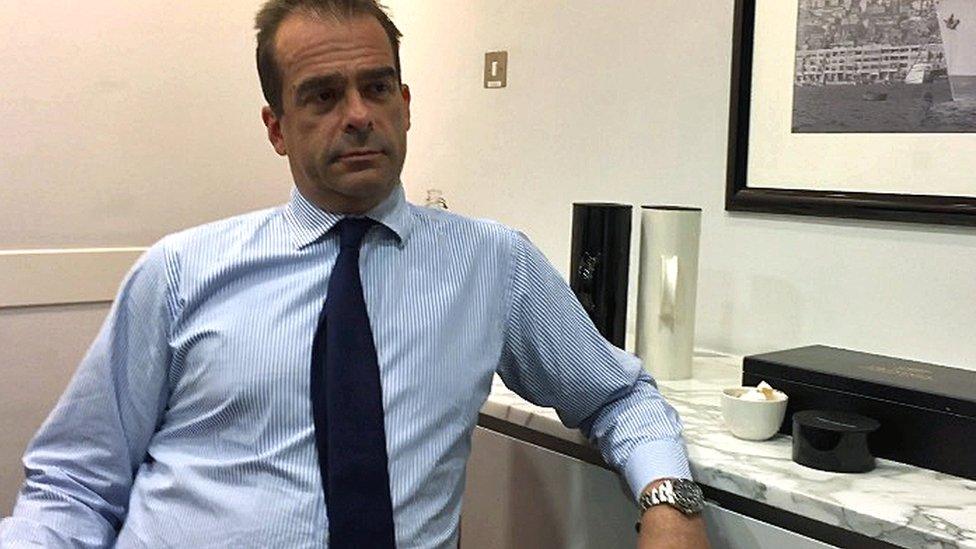

Brian Heyworth says the experience of living is 'completely different' since he dealt with his undiagnosed depression

Similarly Brian Heyworth, now the head of the client strategy business in HSBC's asset management arm, says it took him years to understand his condition.

He suffered a psychiatric breakdown in early 2006. He says the trigger was stress, but his high-pressure, long-hours job in another bank was the catalyst not the cause.

"The blunt reality is that if I had been running a sweet shop I'd have still found myself in the same position".

After his collapse, which he says followed weeks of not sleeping and drinking too much, Brian was admitted to a clinic for two months. There it became clear that he had suffered from depression since his teens.

Brian says the culture and environment in which he was working at the time wasn't conducive to helping him to recognise his illness, but he thinks the failure to acknowledge it goes deeper than that.

"Society, the world in which I was operating, the country in which I was operating - it was taboo."

And he adds: "although huge progress has been made in the UK in the last ten years, it is still quite taboo".

Sharing experiences

It is in an attempt to break this taboo that Sam and Brian are so open about their mental health.

They're part of a network called "Minds@Work", external which has been set up by Geoff McDonald and colleagues Georgie Mack and Camilla Upson. Geoff, a former vice-president of human resources at Unilever, suffered his own bout of depression in 2008.

This week the group held an event where business people, including Sam and Brian, shared their experiences.

Not before time, according to Geoff. Despite the arrival of a younger, more open generation into the working world, he believes it is still "a bastion of stigma", but there is a good business case for companies to be open about depression and anxiety, he argues.

Geoff McDonald believes that being able to talk about his depression, 'literally saved my life'

"More and more companies have got to start thinking about the well-being of their people as a way of ensuring that their people perform well."

Geoff is not a lone voice. Campaigning groups such as Time to Change, external believe that more emphasis on employees' mental health could improve productivity and cut days lost to sickness. Some companies, including Brian Heyworth's employer, HSBC, now have well-being programmes in place.

Healthy workplace

But how does that translate into the real world of the workplace?

Crossrail, which is currently building a railway across London and the surrounding areas, believes - perhaps because of the risks inherent in its work - that the robustness of its employees' mental health is as important as the physical.

Its strategy includes everything from having well-being champions and mental health first aiders on each site, to regular "toolbox talks" where mental health might be discussed, to making sure the canteen offers decent, appetising food.

Do employees take advantage of this support?

Simon Taylor, from the main contractor, and Kadar Duale from Crossrail, are well-being champions for the Stepney Green site

At the company's noisy Stepney Green site in East London, where 320 workers are involved in the construction of a ventilation shaft and emergency staircases, engineer Kadar Duale is a site well-being champion.

"We find it very hard to get men to come to us," he admits, "especially men in construction. They are seen as sort of the hard men."

But, he adds, providing awareness through strategies such as the toolbox talks encourage people to be more confident and more involved in what's on offer.

As Christina Butterworth, who leads the company's occupational health strategy and is on a well-being audit of the site, says, "it's very easy to manage the physical because it's so obvious, it's much more difficult to manage the mental health."

Leadership

Christina says the company's focus on all aspects of its workers' health is beginning to bear fruit, but, as it has found, embedding a culture of openness doesn't happen overnight.

Success depends on a push from the top, says occupational psychologist Emma Donaldson-Feilder. She thinks managers, at all levels, have a key role in promoting good practice - especially in our more stressful post-recession world of increased workload and lower job security.

Emma Donaldson-Feilder says higher levels of stress since the financial crisis are likely to increase the prevalence of mental health problems

Her research shows it's about giving your staff the right degree of autonomy, about modelling a healthy attitude to work yourself and about knowing your team well enough to see when someone is struggling.

"I'm not recommending their manager becomes their counsellor, therapist, or doctor," she says, "but I think as a manager if you can catch the signs early and just sit down and talk through with the person... what support they need, what changes they might make, that can be enough."

Sam Brown echoes this approach, tough as it may be: "Please talk to somebody. I found taking myself to see a psychologist first of all one of the most terrifying things that I have ever done.

"From that moment I didn't start getting better by any stretch, in fact I went quite rapidly downhill, but I felt so much more protected I suppose, that I wasn't doing this on my own."

You can hear more on mental health issues in the workplace on BBC World Service's Business Daily programme here

- Published25 November 2014