Carney: Get real, there are losers from free trade

- Published

- comments

Clement Attlee once said to his troublesome Labour Party chairman, Harold Laski - "A period of silence on your part would be most welcome".

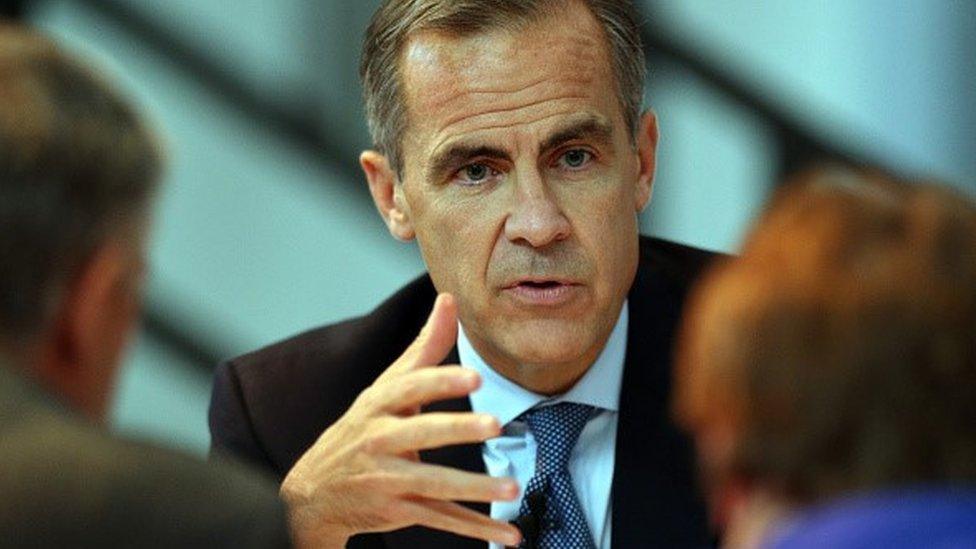

Some present day politicians may think similar of Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England.

After robust and regular statements on the risks to the UK economy following the vote to leave the European Union, today's speech in Liverpool puts the governor at the heart of the debate about rising inequality and stagnant incomes.

He said there were clear losers from the rapid growth of free trade.

Yes, wealth for countries had increased and millions had been lifted out of poverty.

But in developed nations such as America and Britain, some had lost their jobs and had seen their wages fall.

The global elites, the governor suggested, had neither done enough to tackle the problem or even admitted that the problem existed.

That had led to resentment and a feeling among many that they had been left behind.

Tough test

Whatever the arguments about the triggering of Article 50, leaving the EU or the effects of a Trump presidency on the global economy, the debate on the unequal division of wealth will be the one that dominates the national conversation up until the 2020 election.

By then, will people feel - and indeed be - better off in real terms?

Theresa May spoke of building an economy that "works for everyone" - setting a tough test for her government.

Today the governor spoke of building "globalisation that works for all" - setting a tough test not just for central banks but for governments as well.

Including Mrs May's.

Politicians are, after all, in charge of the tax and spending policy levers that are most readily placed to redistribute wealth to those who are missing out on the growth dividend.

Mr Carney's speech went further than the free trade problem.

Echoing warnings from Paul Johnson, the director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the governor said that growth in real incomes was at its slowest rate since the mid-19th century.

Meaty issues

He said that wealth inequality across the West was "staggering" and that in Britain "equality of opportunity remains disturbingly low".

These are big, meaty, issues and raise two intriguing questions in some peoples' minds.

Shouldn't Mr Carney limit his comments to interest rate policy and inflation targeting - the central parts of the Bank's remit?

And, if he doesn't, isn't he in danger of straying into the political arena, always difficult for an unelected official?

I don't believe Mr Carney sees it that way.

Issues such as the good functioning of economies fall squarely within the Bank's remit, the governor believes.

The first line of the Bank's charter was drafted in 1694 and demands that the Bank 'promote the public Good and Benefit of our People" (which at that time meant paying for a war against France, a manoeuvre Mr Carney is not, one assumes, presently contemplating ).

Further, central banks around the world were obliged by politicians to do the heavy lifting of supporting economic recovery following the financial crisis, making their role more prominent in the public's mind.

They are part of the political conversation about who the economy works for, whether central banks are comfortable in that role or not.

Solutions - such as higher levels of productivity or investment in skills - have a direct influence on the Bank's remit to support growth whilst controlling inflation.

Mr Carney also feels the need to respond to the political criticism that ultra-low interest rates and the buying up of government, bank and business debt (quantitative easing) has helped some and disadvantaged others.

Mrs May put it like this: "People with assets have got richer, people without them have suffered; people with mortgages have found their debts cheaper, people with savings have found themselves poorer."

Income inequality

Mr Carney rejects the analysis.

"What has been the distribution of financial outcomes?" he asks of monetary policy.

"Has monetary policy robbed savers to pay borrowers?

"Has the Monetary Policy Committee [the Bank body which sets interest rates and QE policy] been Robin Hood in reverse?

"In a word, no.

"The poorest have gained the most while all wealth quintiles [fifths of the population] have gained since 2006-8."

While stubbornly high, wealth and income inequality in the UK is actually relatively static, he said.

Mr Carney has been one of the most prominent figures in the public debate, both in the run up to the referendum and its aftermath.

He was the first official to speak - reassuring the markets - after Britain voted to leave the EU.

The economy is central to the debate about Britain's political future.

And, as central banks play an ever greater role in supporting wealth creation, Mr Carney believes it is well within his brief to talk about the best route to an economy that works for all.