British business 'loath to invest in research'

- Published

British businesses are not willing to invest in UK research, a situation that has to change, a leading academic has said.

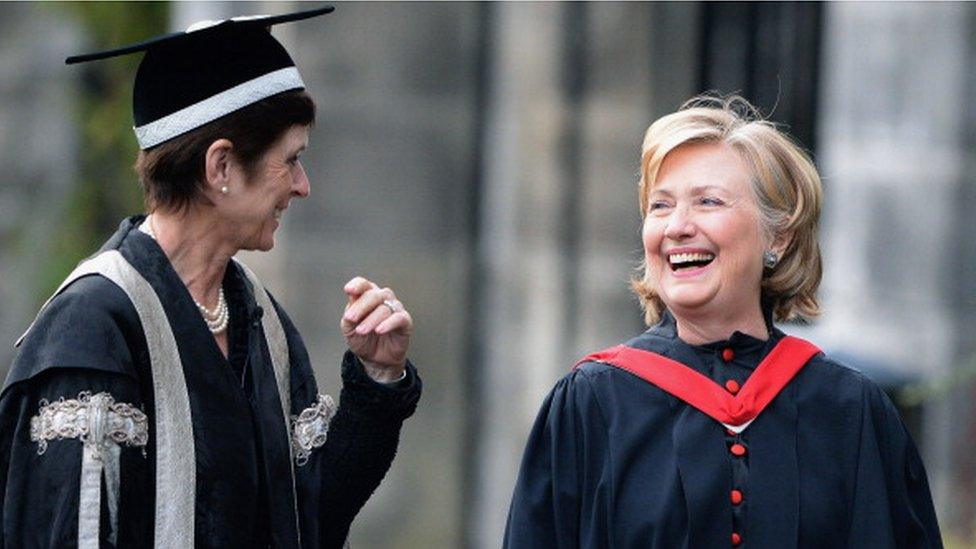

UK firms lag competitors in France and Germany, and are below the EU average said Professor Louise Richardson of the University of Oxford.

Under-investment in the UK has a knock-on effect on productivity.

And foreign investment in British universities means UK research largely benefits companies overseas.

Here's the good news. The University of Oxford will today announce a huge pot of new money to turn the best ideas of its students and graduates into the world-beating companies of tomorrow. The Oxford Sciences Innovation fund has swelled from £320m to nearly £600m in under a year.

What a vote of confidence in our world class universities. Well done Britain.

Er…not quite.

Every last penny of the new money comes from just five investors: three from China, one from Singapore and one from the Middle East. And that, says the university's vice chancellor Professor Louise Richardson, is disappointing.

Professor Louise Richardson (pictured left) says UK businesses must invest more.

"It does speak to the disappointing investment by British industry in research and development. We are way below our competitors in France and Germany and below the EU average.

"In fact, 40% of the R&D spend in the UK is by subsidiaries of foreign companies. British businesses are very loath to invest and that really has to change."

It seems that foreign investors and companies appreciate our universities, while British ones do not.

The brightest talents and ideas fostered in UK universities will largely accrue to the benefit of overseas companies.

It wasn't always this way - until the 1980s British investment in research and development was among the highest in the world.

Now as a country we spend far less than Germany and France and we are well below the EU average.

In fact in the IMF league table of business investment as a percentage of national income the UK comes one-hundred-and-fifty-second, tucked in between Bosnia and Madagascar.

The government seems to have belatedly got the message.

Philip Hammond's recent Autumn Statement pledged an extra £2bn a year by 2020 to research and development, but that will still leave us way behind our European neighbours.

Productivity puzzle

As the Chancellor pointed out, French workers produce more in four days than UK workers do in five. So if we upped our game we could have an extra day off every week.

The government is also looking at ways to get businesses to invest through improved tax incentives.

That has been tried many times before and the lesson of recent years that you can lead business to the waters of innovation but you can't make it drink.

A spokesperson for employers group the CBI pointed to a recent survey of its members which suggested seven out of ten businesses were intending to maintain or increase investment this year.

Those sound like fine intentions. What we know in fact is that business investment has fallen this year and last, even while the economy has grown.

What does any of this really matter? It matters a lot.

If workers become more productive, employers can afford to pay them a bit more, their living standards increase, and the government gets more tax revenue.

If they don't - none of these good things happen. Our standard of living, our public finances, our very quality of life depends on investments in new training, new technology, new machines, and business is not pulling its weight.

The astonishing lack of productivity in our economy was highlighted just this week by Bank of England Governor Mark Carney.

Pointing out the fact that we are less productive than we were a decade ago, he said: "If you think that's odd, it's because it is - it has never happened in the lifetime of anyone alive."

Productivity isn't everything. But in the end it's almost everything. Those are the words of Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman.

It is the defining economic challenge of our age and it's a challenge that UK business is failing.