Mexico and Mr Trump: What will happen to trade ties?

- Published

Donald Trump is not popular in Mexico

Mexico is being blamed by President-elect Donald Trump for taking jobs from the US.

He's been putting pressure on US companies not to move jobs south, and this week Ford announced it was investing in its factory in Michigan rather than building a new plant in Mexico.

During his election campaign, Mr Trump threatened to rip up Nafta, the free trade agreement between Canada, the US and Mexico, which has been in place for 23 years.

But what impact has Nafta had in Mexico, and what would its potential demise mean for the country?

In a leafy square in Mexico City on a warm December evening a group of excited children are hitting a brightly coloured pinata stuffed with sweets. A fellow passer-by explains to me that pinatas are a Mexican tradition, particularly at Christmas and birthdays.

However, Mexicans also like pinatas "in the shape of everything we want to hit", he says. "The latest trend is Donald Trump pinatas," he adds.

A look back at some of the things Donald Trump has said about Mexicans

Mr Trump is not popular in Mexico. He was incredibly rude about Mexicans during his election campaign, and at a time when the world seems to be turning away from free trade he threatened to end the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) between the US, Mexico and Canada.

The important thing about Nafta is that companies importing and exporting between the three countries pay no tariffs. Mr Trump believes it's been bad for the US as cheaper Mexican labour has meant some US manufacturers have moved production across the border, resulting in job losses at home.

Nafta was implemented in 1994 and over the past 23 years Mexico has grown as a manufacturing hub. Today the United States and Mexico trade over $500bn (£400bn) in goods and services a year, equal to about $1.5bn a day. Mexico is the US's second-biggest export market, and the US is Mexico's largest.

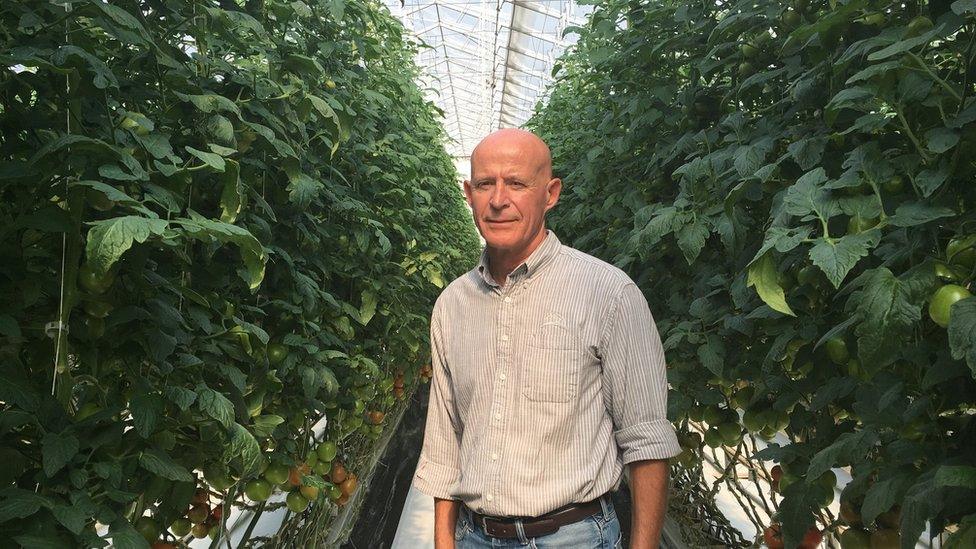

Thierry Legros says without Nafta his farming business would be under threat

Red Sun Farms, a large vegetable-growing firm in central Mexico, depends on the free trade agreement. Its managing director, Thierry Legros, shows me into a vast greenhouse, 200m long, with row upon row of tomato plants. The company also grows peppers and exports 90% of its crop to the US and Canada.

So what would it mean if Mr Trump repealed the Nafta agreement completely with its tariff-free trading? "We might need to close the whole company," Thierry tells me. "It would be around 3,000 direct jobs, so with all the indirect that's quite a lot, probably double that."

Outside Thierry's office three flags flutter in the wind - one for each Nafta country.

The three Nafta flags at Red Sun Farms reflect the company's integration within the free trade area

Red Sun Farms even owns a farm in the US and sends Mexican workers over there. However, there's a stark wage differential, with pay significantly higher in the US.

"Right now with the exchange rate that's huge," Thierry explains, "it's about one to eight, one to 10."

These Red Sun Farms workers in Mexico earn far less than their counterparts in the US

As well as enabling Mexico to export freely, Nafta also opened the door to US imports, giving Mexican consumers much greater choice.

"It was an achievement, it was against history," says economic consultant Luis de la Calle, who was one of the negotiators of the free trade agreement.

"Most Mexicans thought that it was impossible or not convenient to have a strategic association with the US, and many people in the US never thought that Mexico could be their partner."

Find out more

You can listen to In Business: Mexico and Mr Trump on BBC Radio 4 at 20:30 GMT on Thursday, 5 January and at 21:30 GMT on Sunday, 8 January.

Increased demand, as a result of free trade, forced Mexican manufacturers to improve quality.

Luis de la Calle says that before Nafta Mexico had three producers of TV sets, and the quality was "awful". But today, Mexico is "the largest manufacturer of TV sets in the world". They are exported and are "high quality, completely different from the protected market we had before".

The instantly recognisable VW Beetles are manufactured in Puebla, Mexico

Mexico is now a centre of manufacturing for overseas companies, such as the motor industry. General Motors and Ford both have factories in Mexico as well as the US.

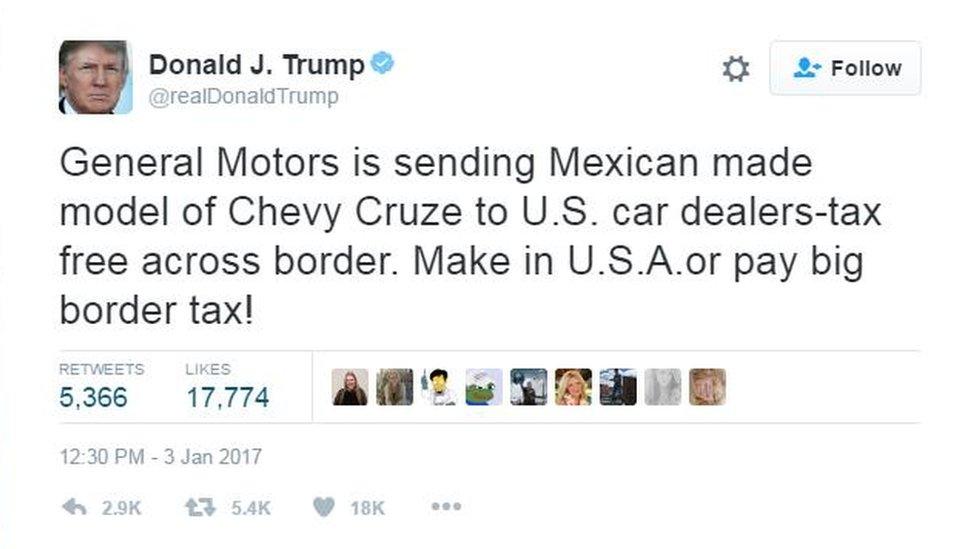

But Donald Trump has put public pressure on US companies not to move production, and has threatened to impose import duties on cars coming in from Mexico. It's a sensitive subject and the American carmakers refused to be interviewed.

Donald Trump had this message for the car industry earlier this week

However, in the city of Puebla, a two-hour drive from the capital, the German car manufacturer Volkswagen is the biggest employer with 14,000 staff. It's the only place in the world where VW produces its famous Beetle, and as you enter the site you're greeted by a display of Beetles suspended in the air like a piece of installation art. The Golf and Jetta models are also produced here.

Thomas Karig from VW Mexico was tight-lipped about whether the firm had come under any pressure about jobs

Like the US carmakers, Volkswagen's Mexican production is integrated with its US plant. "We use a lot of parts coming from the US for assembly here in Mexico in Puebla, and our colleagues in Chattanooga in Tennessee - they use a lot of parts coming from Mexico," explains Thomas Karig from Volkswagen Mexico.

This integration is possible because there are no tariffs to pay each time components are sent from one Nafta country to another. But when I ask whether Volkswagen has come under pressure from Mr Trump about keeping jobs in the US, the atmosphere cools and there is a curt "no comment".

The Nafta agreement has not benefited everyone in Mexico though. Some small farmers were unable to compete with US agricultural imports and big Mexican rivals.

According to a study by the Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research, from 1991 to 2007 some 4.9 million family farmers were displaced. Some found work with big exporting agricultural companies, but there was still a net loss of 1.9 million jobs.

Three of Aurelio's children are illegal migrants in the US

An hour's drive from Puebla I meet Aurelio, whose family has farmed a tiny patch of land since 1925. Deep in the dry countryside he raises a few cows.

Job opportunities are scarce and three of his five children have migrated illegally to the US where they have found work painting cars. But Donald Trump has said he wants to deport illegal immigrants. Aurelio takes out his mobile phone and calls one of his sons in the US. Is his son worried about this, I ask.

His son says that if there is a chance of being deported they will have to look elsewhere, but adds: "Mexico is a tough choice because of lack of opportunities, violence, high taxes and the economic situation, so it wouldn't be easy."

President Obama has deported at least 2.4 million illegal immigrants so this isn't a new policy. And according to the Pew Research Center, by 2014 more Mexican immigrants returned to Mexico than migrated to the US.

Luis de la Calle says both the US and Mexico benefit from Nafta

Mr de la Calle acknowledges that the free trade agreement has split the country. He says there are two types of regions in Mexico.

"[There are] parts of the south of Mexico that are disconnected from international trade, that are lagging behind, where Nafta had little impact. Rates of growth are low, there is little investment, and you don't see large manufacturing operations."

In contrast to this, he says: "There are 16 or 17 other states that grow very fast, you see a lot of dynamism." These he describes as "Nafta states" with exporting businesses.

However, he dismisses Mr Trump's criticism of Mexico. "He says [Nafta's] been great for Mexico, actually his whole argument is that Mexico is doing so well. It's flattering."

He also claims that the US is benefiting from its close manufacturing links with Mexico.

However, when I ask who would come off worst if Nafta were repealed, the US or Mexico, he answers, "Mexico because we are smaller, but the US would lose quite a bit as well."

Donald Trump wasn't the first US presidential candidate to criticise Nafta. Hillary Clinton and even Barack Obama did so on their campaign trails.

But abandoning it completely? The US may find it has too much to lose and perhaps Mr Trump has realised that too.

In Business: Mexico and Mr Trump is on BBC Radio 4 at 20:30 GMT on Thursday, 5 January and at 21:30 GMT on Sunday, 8 January.

- Published3 January 2017

- Published3 January 2017

- Published9 November 2016

- Published11 November 2016

- Published27 September 2016