How to stop your career stagnating like Reggie Perrin's

- Published

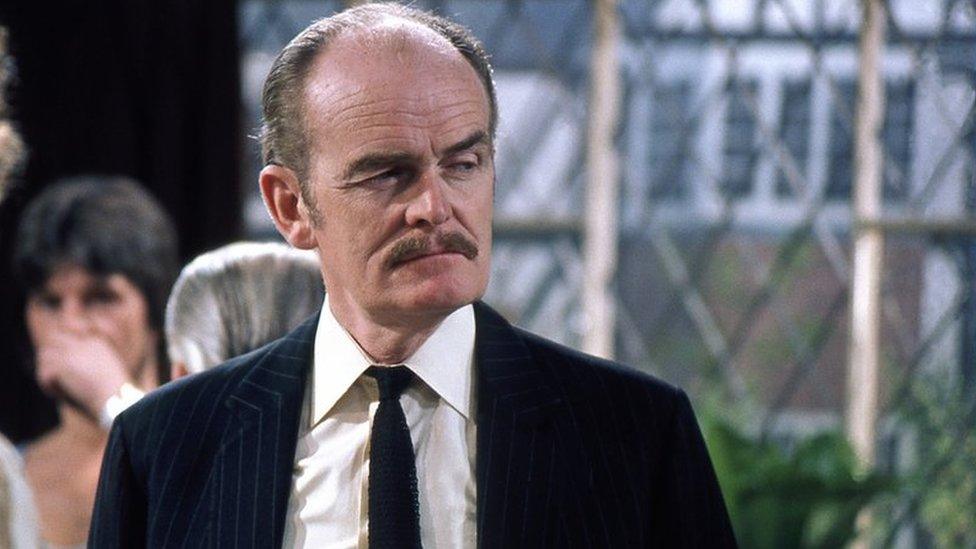

Mid-life crisis: frustrated middle manager Reggie Perrin with his long-suffering secretary Joan Greengross

If you're of a certain age, or a fan of 1970s sitcoms, you'll know who Reggie Perrin is.

The eponymous hero of The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin is so bored with his job as a manager at Sunshine Desserts that he fakes his own death so that he can start a new life.

Forty years on from Reggie Perrin's world, the default retirement age has been scrapped and the government is urging those over 50, external not to down tools and leave the labour market.

So, if we really are all going to be working across four or even five decades into our late 60s or beyond, how do we avoid the Perrin-esque feeling of heading down a cul-de-sac?

Ditch convention

The career path many of us embark on could be described as follows: learn the job, do the job, get promoted, become a manager - and perhaps stop doing the job that we've actually got quite good at.

Clive Hutchinson aims to retain employees by allowing them to play to their strengths

In some cases that promotion might come after what Clive Hutchinson, the owner of engineering firm Cougar Automation, calls "the tap on the shoulder".

In his industry that tap heralded a move from engineer to the better paid role of project manager. But in his opinion that convention didn't play to people's strengths.

"You'd have a really good engineer who wanted more money and more status and recognition, and it took him away from being a really good engineer and often into being a really bad project manager."

When Clive and his business partner took over the company in 2003 they decided that, in order to meet their target of giving their customers the best possible service, they needed to change the way they looked at career progression - to reconcile people's desire to get on with keeping them in the roles they were best suited to.

Their answer was to make both the salary and the grading structure much more flexible.

They introduced a transparent pay system and a martial arts-based framework of banding for all the roles within the company.

Jim Allen says he is very much an engineer, not a manager, and prefers to leave that to other team members

Project managers were no longer automatically paid more than the rest of the team, it was easier to move to different projects, and the new freedom meant experienced engineers felt they had more options than before.

"I got very frustrated," says Jim Allen, a software engineer at Cougar, of his experience of being a manager. "I just didn't enjoy coming in in the mornings.

"At the time I thought, 'What can I do? I've got no way out of this, perhaps move offices, move companies even, and go back to engineering.' And fortunately here they said, 'There's no problem coming back to being an engineer.'"

'Lifelong learning'

Jim returned to a job he describes as "massively broad" with the added incentive of a "bit of a pay rise", but as an engineer with 20 years' experience, he says that at his stage the job is actually more about how well the project went than large leaps in salary.

Research backs him up on that. Figures from one study, external suggest that workers might see pay growth of 60% in their 20s, but then see that increase slow, with a salary peak for women at 39, and for men at 48.

That leaves a lot of years of work ahead.

Salary can't be the only motivator, says Dr Jill Miller

Dr Jill Miller, a research adviser at the CIPD, the professional body for HR and career development, says the secret to keeping motivated is what she calls lifelong learning, as much as salary.

"It's more about development opportunities," she says. "So it's work that's fulfilling, inspiring, engaging and it challenges people because I think... being bored sometimes can have detrimental effects of being stressed and that's what's going to cause people to be demotivated and leave the organisation."

'Keep employable'

Ros Toynbee, director of The Career Coach, agrees. She sees people who are often a few years into their working lives and have suddenly found they've fallen out of love with their workplace, whether it's because they've reached a milestone in their lives or they're not getting the opportunities they want.

"It may be that they're being ignored by a boss, they're not being recognised," she says. "They want to be able to progress, but are finding for some reason they can't."

Make sure the work culture suits you and keep doing things you find interesting, advises Ros Toynbee

So what advice does she give most often to those who feel their career has run into the sand?

"The most important thing is to keep on doing interesting things that keep you employable. Be looking out for trends, and training yourself. Don't expect your company to pay for you, because many will not."

'Senior conversations'

Ms Toynbee's advice to choose skills that will ensure "longevity of career" is echoed by professional bodies such as the CIPD, as it anticipates a workplace populated by an increasing number of over-50s.

It's a change that is already happening - in 2016 there were 9.8 million people over 50 in employment in the UK, compared with 5.7 million 20 years earlier.

Nevertheless, the proportion of older workers in employment drops sharply between the ages of 53 and 67.

In its report, external on how we can achieve longer and more fulfilled working lives, the CIPD suggests employers should adopt a system of career reviews for older workers where their development needs are discussed.

And it says the UK could follow the example of countries such as Denmark, where many companies regularly hold "senior conversations" with their employees, covering all aspects of their career.

Reggie Perrin's boss CJ: possibly not a fan of career reviews

Would a senior conversation with his unappealing boss, CJ, have made Reggie Perrin feel less despairing about his job? Maybe not.

Better advice for him, perhaps, comes from the CIPD's Dr Miller who thinks we could all take a leaf out of the millennial generation's book by not expecting a job for life and being content with moving sideways, rather than up.

"Younger workers perhaps have more of a mindset that they have more options," she says, "that it's not like you need to choose a career when you first enter and stick with it and grow within it. They've got more of a fluid mindset."

- Published1 February 2017