Barack Obama legacy: The president and the tale of US jobs

- Published

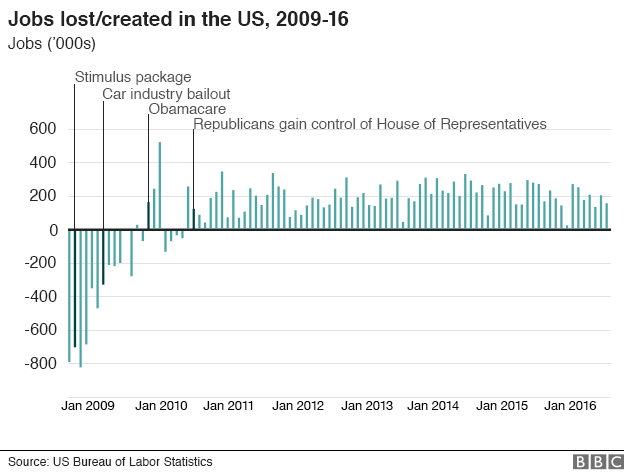

Economists and economics reporters do like their charts and graphs.

And if they were all forced to pick just one with which to tell the story of the Obama presidency, many would plump for the bar chart of "non-farm payrolls".

The non-farm payrolls report is simply the official measure of how many jobs the US economy has added (or lost) in the previous month.

The release of this job tally, which happens at the same time, on the same day (the first Friday) of every single month, is one of the constants in the working life of a Wall Street economist or reporter.

Many feel they measure out their lives with non-farm payroll reports.

800,000 per month

But you can reasonably measure out the Obama presidency with them as well.

Take a look at the chart.

On it you can see that from the first such report after entering the White House, President Obama learned that the US economy had just shed 800,000 jobs in one month.

No other figure so clearly illustrates that Mr Obama started his presidency with an economy that wasn't just weak, it was on the verge of collapse.

A recession of a severity not seen since the 1930s was under way.

The most pressing question for the new president was what, if anything, could be done to stabilise the economy so that it could create jobs once more.

’Yes we did’: Obama on Iran, Cuba and healthcare achievements

The chart shows us what happened.

By early 2010 the monthly tally shows the US was adding jobs again

And albeit with further dips later that year, it has done so ever since.

The last non-farm payrolls report of the Obama era showed that in December 2016 the US economy added 156,000 jobs.

It was also the 75th consecutive month of job growth.

There has never been such a long period of job creation.

The official unemployment rate in the US is now 4.7%. For many economists that represents "full employment".

But the chart doesn't tell us WHY the job market bottomed out and started its long expansion.

For an explanation of that you might start with one word: Detroit

Auto bailout

Detroit, or rather the US car industry with which the city is synonymous, was seemingly in its death throes in January 2009.

The recession and financial crisis had hit General Motors, Chrysler and Ford particularly hard.

US "car tsar" Steve Rattner discusses President Obama's economic legacy with the BBC's Michelle Fleury

Already heavily indebted, by the turn of the Obama administration it looked like they would simply run out of cash and cease operations within weeks.

President Obama's decision to bail out General Motors and Chrysler with bridging loans and managed bankruptcies (Ford managed to turn itself around without government money) was deeply controversial.

But look again at the chart.

If the auto industry had in fact collapsed, we would probably need to spread something like a million more job losses across those bars for 2009-10.

Beyond the number of jobs directly or indirectly lost, it's hard to calculate the ultimate economic effects of a disintegration of the US auto industry.

But it seems safe to say that America would look very different indeed without the auto bailout.

Stimulus

There was also Mr Obama's stimulus package - or the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, to give it its official name.

This was a package of government spending which Congress passed, at the new president's behest, within weeks of his taking office.

There have been 75 consecutive months of job growth in the US

It too met fierce criticism and its impact has long been disputed.

Still, more than one analysis has estimated that through 2010 it created or saved more than 2 million jobs.

Taking those away would also dramatically alter the non-farm payrolls chart.

At least it would for the beginning of Mr Obama's presidency.

Levers of power

But after the first two years of his administration the politics of job creation, like everything else, changed.

The Republican Party's capture of the House of Representatives in November 2010 deprived the president of most of his influence on the writing of new laws.

He lost his grasp of one of the main levers of economic control and never regained it.

The Democrats lost control of the House of Representatives in November 2010

That means that so much of the long period of job growth, from 2011 to the present, has unfolded with little input from the White House.

Of course the president always has large powers, whoever controls Congress, but they tend to be in the administration of business regulations and in trade relations.

Attributing the creation of jobs to those functions of government is even more speculative than attributing them to new laws.

Gridlock

Still, if presidents cannot write laws, their veto power means laws can hardly ever be passed without them.

It is a feature of the notorious political "gridlock" that has characterised much of the Obama era.

The president and the Republican Congress have been in a perpetual stand-off over so many issues at the heart of the economy.

The result is that many economic problems have gone unaddressed.

Yet it also means that politicians, and their insistence on change and reform, have been kept on the sidelines, leaving the economy to develop without them.

In the absence of major external shocks, perhaps the consistent job growth the US has enjoyed for more than six years should be attributed, not to the name and the politics of the president but to things more fundamental to the US and its brand of capitalism.

It seems appropriate that after the steep steps down, then up, in the first 18 months of the non-farm payrolls bar chart, what the Obama presidency looks like is then a consistent series of bars, representing steady if undramatic job growth, month after month after month.

- Published12 January 2017

- Published10 January 2017

- Published10 January 2017