The long-distance learners of Aleppo

- Published

Mariam has to study by candlelight and use a shop's generator to charge up her computer

Mariam Hammad, despite every adversity of war and hardship, is trying to be a student in Aleppo in the dark heart of Syria's civil war.

"My city has turned to ruins," she says.

Despite being in constant danger, forced out of her home twice by shelling and living without regular supplies of electricity or water, this 22-year-old has refused to give up being a student.

Four years ago, she had just left school and begun at the University of Aleppo when it was hit by rockets, killing dozens of students around her.

"I saw my friends killed and still now I can't forget what happened," Mariam says.

"I saw a lot of students hurt and injured. There was blood, death. Everything was terrible."

'Everything destroyed'

There was intense danger at home too.

"I came so near to death many times," Mariam says.

"My family and I rented a house that was only 500m from the front lines, and a lot of rockets fell in my neighbourhood.

Mariam has refused to give up her ambition to be a student and get a degree

"Many of my neighbours were killed, and mortars hit my home twice."

She remembers waking during an attack, unable to see in the dust and darkness and not knowing who was alive or dead.

Mariam talks of life in Aleppo becoming a mix of "horror and danger".

"I was crying so much when I saw my city in front of my eyes, everything destroyed," she says.

Choosing optimism

But her reaction has been to stubbornly carry on and to use her studies as a way of honouring those who have died.

She became an online student in a warzone, following a degree course run by the US-based University of the People, external, making a conscious decision to be "optimistic" and to make plans to "rebuild".

This week in Aleppo the temperature has fallen below 0C

But this is far from straightforward, she says over a patchy Skype line.

"The hardest thing about being a student in Aleppo? Actually, it's being alive," Mariam says.

There are still occasional rockets and mortar blasts, despite a ceasefire, but there are also big practical problems that would have put off a less determined student.

Charging phones

"We haven't had electricity for two years," she says.

Instead, people rely on generators that might operate for a few hours at a time.

Mariam goes to a local shop with a small generator, where it can take 12 hours to charge up her mobile phone and an old laptop, and then she ekes out the charge so she can study.

Families are living in the wreckage of their city

Internet connections are sporadic and weak - and when an exam was approaching, there was an internet blackout.

Worried that she would be failed, Mariam began to make preparations to travel to Damascus to find a way of sitting the exam.

Even by the standards of a civil war, she says, this would have been extremely dangerous, but friends managed to make contact with the university, and she was able to re-arrange the exam.

More stories from the BBC's Global education series, external looking at education from an international perspective, and how to get in touch.

You can join the debate at the BBC's Family & Education News Facebook page, external.

Heat and light are daily challenges, particularly in winter, with temperatures in Aleppo below freezing this week.

Water is available only every three or four weeks. "When we have water, we store huge amounts," she says, filling every container.

'Normal day'

There have been long battles between government and rebel armies in Aleppo, but there are also forces of the so-called Islamic State not far from the city.

Mariam says they tried to cut a road to the city a few days ago - but she says there is also the battle of ideas and the need to protect the right to education.

Their presence makes her even more determined to keep studying.

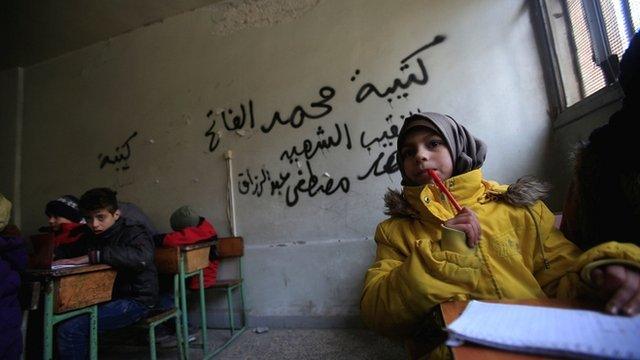

Despite the dangers, the hunger for education has remained in Aleppo

While the high technology of war has rained down on Syria, this young woman has to study at night by candlelight.

But she doesn't complain. Instead, she talks with understated longing for one single "normal day" as a student.

And what would she do with it?

"I want to do a lot of things in this day," she says.

"I want to go to my university like any normal student. I want to go with my friends. I want to sit with my family."

She pauses. "And I want to see everyone I lost," she says.

Rebuilding a future

But in the face of such awful destruction, why is she worrying about getting a degree?

Mariam says the experience of war has made education seem even more important - something positive that links people to the chance of rebuilding a better life.

Carrying bread in the streets of Aleppo

"We have this strong motivation to seek it no matter what," she says.

"You can see that in young children going to their schools, even though they can be hit at any time."

"Education was always important in my life.

"It gives me hope that I can have a better future.

"It will help me to rebuild my country and everything that's been destroyed."

Mariam is studying a business degree with the University of the People, based in California, which supports people around the world who otherwise would not have access to university - including 15 students in Aleppo.

The ceasefire has made it safer for civilians to walk in the street

The online university, backed by the likes of the Gates Foundation, Hewlett Packard and Google, offers accredited four-year degree courses, taught by volunteer academics and retired university staff.

The university's president, Shai Reshef, says: "We are an alternative for those who have no other alternative."

Mariam sees her studying as a kind of lifeline and source of hope - and she says any other students around the world should appreciate the chances they have.

Students were killed when the University of Aleppo was hit in 2013

She can only dream of having a "normal life like them".

"I hope that whoever sees my story will not be discouraged by difficulties they face," she says.

"I believe that after every hardship comes a great rebirth, and in honour of ever friend, neighbour and Syrian who lost his life due to this war, we must stay optimistic."

And if that faith wavers?

"If I feel down, my mother says to me, 'This will pass.'"