Trump's weapon in trade war

- Published

- comments

There is a three letter word that ends in "x" which gets people hot under the collar and is a big part of most relationships.

That word is of course tax.

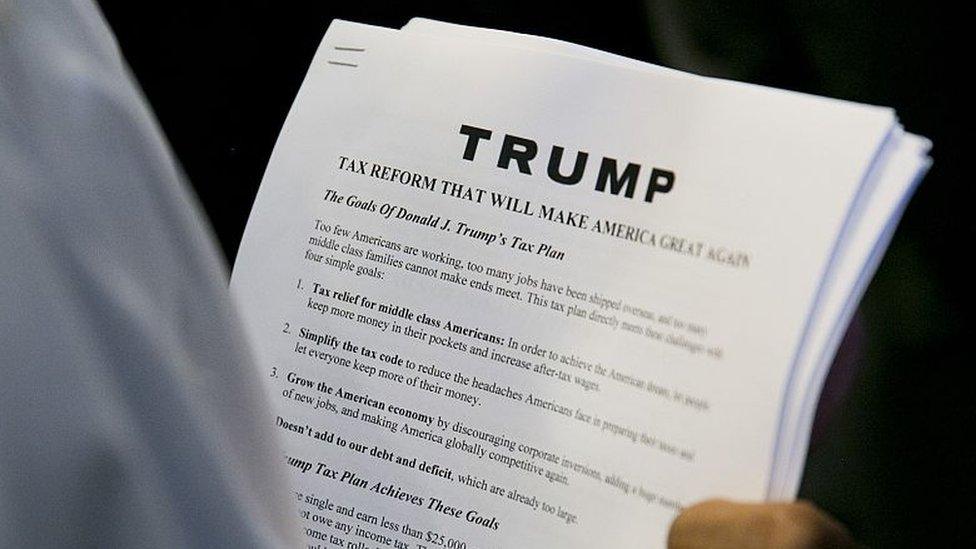

While the headlines from Donald Trump's first 12 days in office have focused on immigration and security, business leaders seem agreed that some of the most profound changes to the role of the US in the global economy will come about via tax reform.

It is easy for eyes to glaze over at the mention of tax.

Not only is it an unsexy subject, there have also been many false alarms sounding the imminent overhaul of a tax system that all parts of the political spectrum agree needs fixing.

The US has some of the highest corporate tax rates in the world.

At 35% it is nearly double the UK rate of 20% and that has seen US companies go to extraordinary lengths to avoid paying it.

Although US companies pay 35% tax on profits generated in the US, it is only payable on profits made outside the US when those profits are repatriated.

That is why those foreign earnings never do make it home.

Stoking a trade war?

Some $2.5 trillion of US corporate profits are living in exile.

They are lapping round the borders of low-tax jurisdictions like Ireland and Luxembourg, or squirrelled away among the palm trees in no-tax hideaways like Bermuda, the Cayman Islands or the British Virgin Islands.

Donald Trump believes that dormant cash should come home to boost the US economy and he is proposing a tax amnesty - a one off charge of just 10% on repatriated cash - to achieve just that.

That sounds simple.

It is not, according to Professor Christopher Smart, a former trade and investment advisor to Barack Obama, and a senior fellow at Chatham House, a leading international affairs think tank.

"The potential is for a great deal of instability both on financial markets and politically," he says.

"On financial markets a large amount of money moving quickly tends to destabilise things but the real political issue is the potential for retaliation.

"Barriers we have been removing over the last ten to twenty years start to go back up again. We could get trade skirmishes, we could get a trade war," the professor warns.

The second part of Donald Trump's tax plan could be even more provocative.

As well as a one-off amnesty for exiled profits, the new president's plan involves slashing the headline rate of US corporation tax to 15% from 35%.

At the same time he wants to impose taxes on imports to encourage companies to locate production in the US.

A border tax on US cars made in Mexico is just one example of a policy that would have profound, and many say chaotic, ramifications.

Retailers, for example, would find it almost impossible to make a profit on imported goods.

John Viemeyer, the global chairman of the huge accountancy firm KPMG, sounds a similar warning.

"You can't look at US tax in a vacuum, you push here and there will be equal and opposite reactions," he says.

"There's been a lot of talk about border taxes on imports that US companies use in their production, that in itself could certainly cause a trade war"

To many observers, President Trump's spat with Mexico is just a bit of sparring before the heavyweight clash with China.

There are many close to the new president who think the current relationship is unfair and needs to change.

Anthony Scaramucci, a senior adviser to the president, told the BBC recently at the World Economic Forum gathering in Switzerland that the relationship with China was "asymmetrical", and that he was doubtful of China's ability to exact revenge on the US.

"What are they going to do, [are] they going to move against our move for fairness?" he asked, pointedly.

"That's going to cost them way more than it is ever going to cost us, and I think they know that."

Who wins a US-China trade war? That is simple, according to Christopher Smart.

"No-one. There is huge fallout for the United States and for China and frankly for the global economy," he says.

Who said tax was boring?