Tupperware: How the 1950s party model conquered the world

- Published

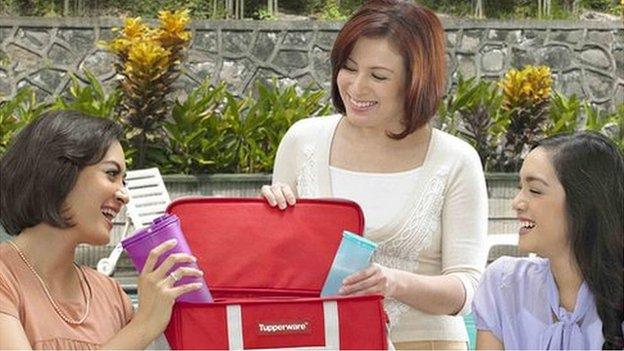

Tupperware parties are no longer polite gatherings over tea and cake, but have been updated to "a girls' night out"

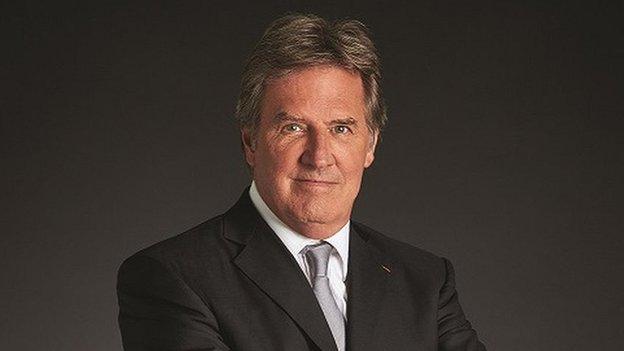

When I meet Tupperware Brands boss Rick Goings there's a funny moment. He's just finished his lunch, but wants to pack the remainder away for later.

He looks expectantly at his colleague, expecting her to magic a box out of thin air. "What, you think I've got some in my handbag?" she scoffs.

You can tell Mr Goings is slightly disappointed. The King of Tupperware hasn't got any at just the moment he needs some.

Yet, despite being in Switzerland, thousands of miles away from the firm's headquarters in Orlando, Florida, it's not an unreasonable expectation that Tupperware's products may indeed be available.

For while Tupperware may, in the UK at least, be forever associated with a bygone era when women stayed at home and men went to work, it's now a thriving international juggernaut.

"We do not look at ourselves as a US company," says Mr Goings.

Rick Goings says the firm now targets countries "where most of the people in the world live"

And you can see why. Sales last year, external were $2.2bn (£1.8bn) with Asia-Pacific responsible for almost a third of these, while the biggest sales growth was seen in Brazil.

The firm's products - which now include not only Tupperware, but also several beauty brands - are sold in more than 80 countries, and for the past five years, more than 90% of sales have come from non-US markets.

It's a revolution Mr Goings has driven. When he became chief executive in 1997, the firm had already expanded overseas, but was failing. In his first week at the helm he had to write off $100m of bad debt.

"So much was broken," he says about the company, founded in 1946 by inventor Earl Tupper.

His solution was to ramp up the firm's expansion overseas, in particular focusing on Latin America, Asia and Africa and eventually taking the firm to more than 20 additional countries.

He says this shift in focus was obvious, given that Europe and the US combined account for just a tenth of the world's population overall.

"We didn't have to make major changes to our business model and it's where most of the people in the world live," he says.

A recommendation from a friend is always likely to be more persuasive than one from a company, according to McKinsey

Many big consumer brands from Coca-Cola to Procter & Gamble have followed similar paths into emerging markets, tapping into a growing middle class and strong demand for well-known US brands.

Yet Tupperware's model of direct selling - the famed suburban housewives' gathering of the 1950s and 1960s - is exactly the thing that has given it an edge.

While easy to mock - do modern women really get excited about plastic boxes? - it's enabled the firm to get around all the problems of trying to sell in regions where infrastructure is less developed and shops can be a long distance away.

The firm hasn't had to invest in shops, and instead of travelling into town, people can nip over to a friend's house to buy things.

And while the party attendees may start off as housewives, they're unlikely to stay that way, according to Mr Goings. For many of the firm's 3.1 million casual sales consultants, it has provided their first chance of an independent income.

Typically a party will yield about $400 (£320) worth of sales, of which the sales consultant will earn 30%.

"It's a heck of a lot of money," Mr Goings says.

Working for Tupperware has enabled Indonesian Ng Chiu Gwek to educate her three children overseas

Ng Chiu Gwek, one of Tupperware's most successful Indonesian sales force members, who joined the company in 1997, says she loves the firm.

"I have changed my own life into a better life, going from nothing into something," she says.

Previously a full-time housewife, Ms Gwek - who was introduced to the firm by her mother-in-law - now runs a distributorship, responsible for a team of several thousand sales consultants in her hometown of Pontianak and the surrounding small cities.

The job has enabled her to educate all three of her children overseas.

"Tupperware is my life and I have not seen any other company like Tupperware that has changed so many lives for the better," she says.

A Tupperware party is held somewhere in the world every 1.3 seconds, the firm claims

A shake-up of the party format has also helped drive growth. They are no longer polite gatherings over tea and cake, but have been updated to "a girls' night out", says Mr Goings with a conspiratorial nod.

Themes include Mexican night with tequila, and decadent and delicious desserts and meals, with one such party held every 1.3 seconds globally, the firm claims.

In some countries, where small homes mean space for hosting gatherings is limited, the firm has opened so-called "experience studios", where would-be customers can see the products in action. In China it has 5,600 such spaces, but reckons there's capacity for 20,000.

The firm's sales model has another advantage. A recommendation from a friend is always likely to be more persuasive than one from a company, but in emerging markets this is particularly so, according to McKinsey.

The management consultancy found, external consumers in Africa and Asia were far more dependent on word of mouth, than their developed counterparts. It said this was because with few brands around long enough to have built a loyal following, seeing a friend use a product was reassuring.

It's also tough for counterfeiters - and those making cheaper imitations of the products - to imitate this kind of sales network.

The firm's airtight storage boxes that wowed Western consumers in the postwar years now account for just a third of sales

Neil Saunders, managing director at consultancy Globaldata Retail, says while in developed markets like the UK the firm's long history means Tupperware is seen as a bit old-fashioned compared to more modern rivals such as Joseph Joseph, in emerging markets it doesn't carry this "baggage".

"For consumers there it's a modern innovative brand. It's a challenger and innovator," he says.

And as Mr Goings is at pains to point out while handing me the firm's brochure, the airtight storage boxes that wowed Western consumers in the postwar years now account for just a third of sales.

Instead it is now brightly coloured microwaveable pressure cookers, mini food processors and water bottles that are driving sales.

"The party has changed, the product has changed. We're not just a plastic box company," he says.