Ivory Coast's cocoa farmers face financial crisis

- Published

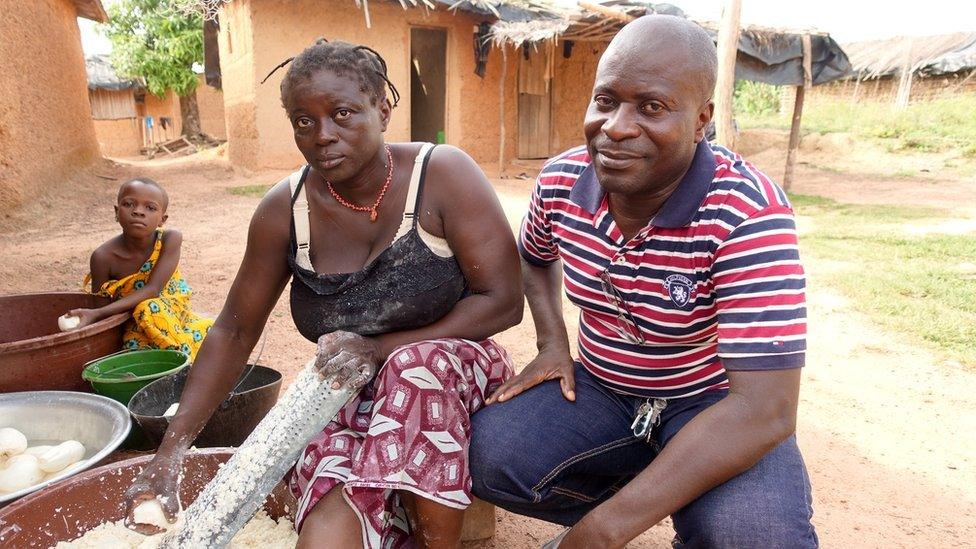

George and his wife Janine are eating cassava, they say they can't afford fish at the moment

50-year-old cocoa farmer, George Koffi Kouame, looks over at his wife, who's grating cassava into a large tub. It's the only thing they can afford to eat at the moment.

"I go to the kitchen and there's no fish, nothing," he says. "What are we supposed to eat?" George harvested his cocoa in October but still hasn't been paid for it.

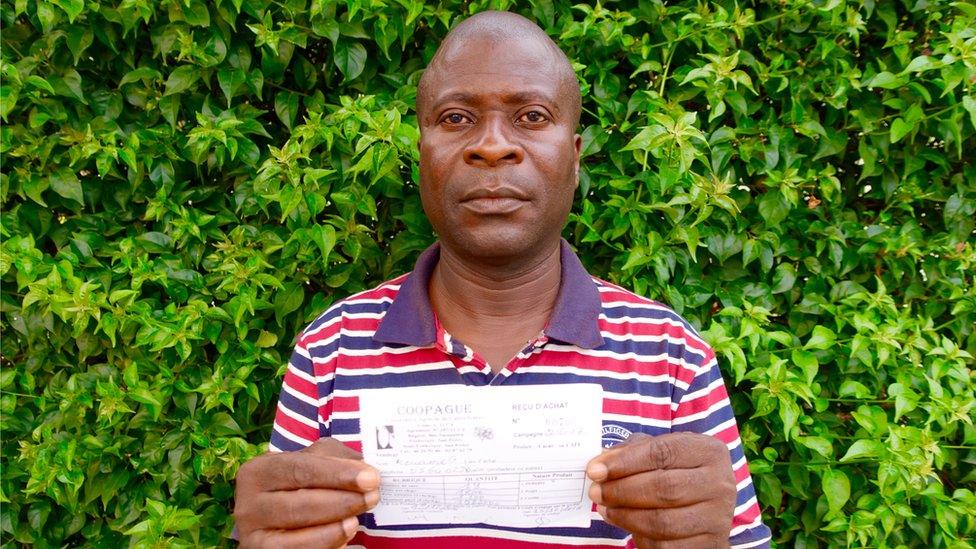

"I delivered 1.8 tonnes of cocoa, but up until this day I haven't received any money," he says, reaching into his pocket to pull out the receipt as proof.

"If there's no money, what can I do?" he asks.

"The money from cocoa supports the farm, the family and it sends my children to school."

Ivory Coast is facing an unprecedented cocoa crisis and it is all down to the price.

The international price has fallen sharply since the end of 2015, in part due to abundant supply and weak demand.

Parts of the world like China and India haven't caught up with Europe and North America in their love of chocolate as quickly as was expected.

George with the receipt he received as proof of delivery last October. So far he hasn't been paid

The price is down 40% from July last year. That coupled with the fact that the Ivorian government raised the price that farmers get has meant cocoa buyers, who buy their stock a year in advance, suddenly faced massive losses if they honoured their contracts.

Up to 80% of buyers have backed out of their contracts, leaving farmers like George penniless.

Twenty kilometres from his village along the coast in San Pedro, the problem is suddenly very evident.

This is the world's biggest cocoa port and the traffic is usually unbearable; huge articulated lorries pounding the pot-holed roads, street vendors peddling goods and food on every corner. But today it's quiet.

The factories are closed. Trucks full of cocoa are backed up along the roads quickly clogging up the streets. The city has almost ground to a halt.

Outside one factory I counted nearly 150 lorries packed full with cocoa parked up on the side of the roads. More are coming every day.

Drivers have been sleeping near their trucks as they wait to unload their cocoa at the port of San Pedro

"I've been here for a month and 15 days," says one truck driver, who has rigged up a hammock underneath the trailer as a makeshift bed. "We have to sleep with the truck because of the thieves.

"We keep being told there isn't any place to unload the cocoa, just be patient and wait." He shares a cup of tea with one of the other drivers. Even in the early morning, the heat and humidity are oppressive.

At the Catholic Church in the heart of the city, 20 presidents of cocoa farmers' cooperatives from around the region meet. Between them they represent almost 20,000 farmers. And they're angry that they can't pay their children's school fees, feed their families and prepare for the next harvest.

"Why is our cocoa blocked?" asks one farmer. "We just can't go on like this. Something has to be done," says another. "If we had guns, then the government would listen to us."

It's estimated about six million people are dependent on the earnings from cocoa in Ivory Coast - more than a quarter of the entire population.

It's the backbone of the economy, amounting to a quarter of total exports and around 15% of state revenues.

If the industry is paralysed, it affects everyone. And as the world's largest exporter of cocoa, the effects on the chocolate industry itself are already being felt.

Cocoa is also piling up in the warehouses around the port of San Pedro

"If the crisis remains there will be a great impact on the prices," says Ivorian economist Yousef Carios. "That could have an impact on the final industry which is chocolate and also the cocoa on the financial market could be impacted too."

Ivory Coast's Coffee-Cocoa Council has a special cocoa stabilisation fund stored in Ivorian bank accounts designed to smooth out price problems like this, as well as a reserve fund at the Central Bank of West African States.

Neither, however, has been touched. Farmers claim that that means they're empty.

The Council insists they're not and has ordered an ordered an audit to prove it. Director general Massandje Toure-Litse says they are trying to sort out the situation.

"We are working with the port authorities to do everything we can to return things quickly back to normal," she asserts, claiming that these measures will help the situation more quickly than dipping into the funds.

"We know that things are being done to sort this out. We are working hard to set things right," she repeats, insisting that this isn't a crisis, the cocoa isn't 'blocked', and that things are just simply taking a bit longer than usual.

Back in Petit Nado, George's village, we walk to the plantation. It should be bustling with workers at this time of the year, preparing for the next season, but it's completely empty.

"We're scared for the next harvest because up until now we don't have the money to pay for fertiliser," he says.

"Without fertiliser you can't grow anything. The trees are old, without fertiliser there's nothing," he tells me, reaching to grab a handful of the dead leaves off of the rotting cocoa tree.

"I'm scared," he says. "I'm scared for the future of my children."

Ivory Coast's cocoa crisis could mean somewhere down the line people save a few pence on their chocolate bar. or maybe higher profits for others.

The country's never seen a cocoa crisis like this before and if it's not sorted out soon there are fears it could push cocoa prices down even further, putting pressure on the lives of millions of people.

- Published1 December 2016