India says UK free trade deal will take years

- Published

- comments

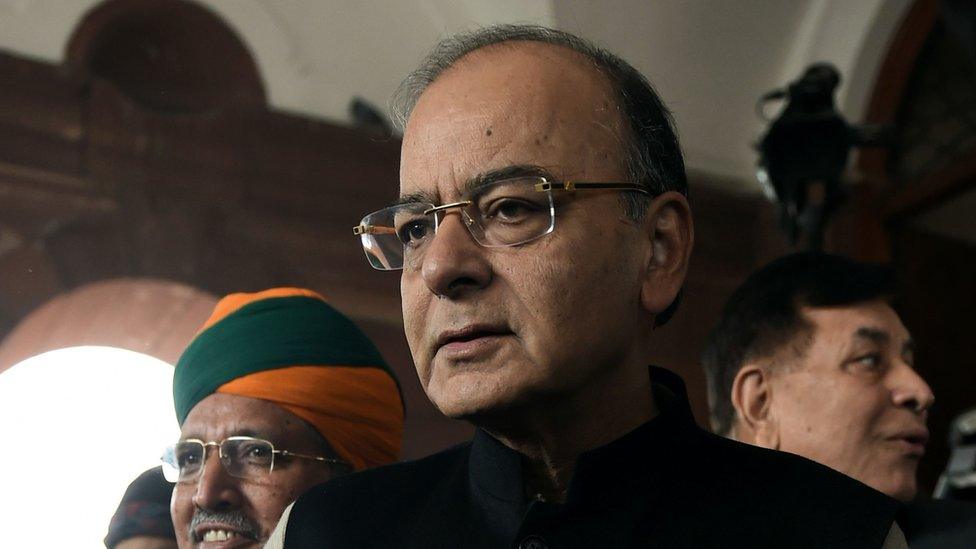

Arun Jaitley, India's finance minister

India's finance minister has said that a free trade deal with Britain will take a "long time" and that no negotiations will start until the Brexit process has been completed.

On a visit to the UK today to meet the chancellor and the foreign secretary to discuss trade, Arun Jaitley said there was "great enthusiasm" for a deal.

But he made it clear that any talks would have to run "in parallel" with current Indian negotiations with the European Union (EU).

The EU and India launched free trade talks in 2007 but progress has been slow.

I asked Mr Jaitley if he thought a trade deal with Britain would be easier than executing a trade deal with the 27 members of the EU.

"Both will move [in] parallel," Mr Jaitley answered.

"Both will move separately, each one will have its own dynamics and as far as the UK and India are concerned we are today at a stage where unless article 50 is invoked - and thereafter the Brexit negotiations are completed and the UK is eligible to negotiate agreements - there can be a formal dialogue and agreement only at that stage.

"So there is a waiting period. But I do understand there is a great enthusiasm in both countries and in the governments of both countries to move forward," he added.

'Extremely important' relationship

India is central to the British government's plan to show that it can secure free trade deals with non-EU countries, particularly countries like India with strong historic ties, rapid growth and over a billion consumers.

Theresa May visited the country last autumn, her first trip to a non-EU nation following the referendum result.

But any expansion of trade with India, as my colleague, the BBC's South Asia correspondent Justin Rowlatt reported is not a given.

Disputes over access for the UK financial services sector to the jealously guarded Indian market, as well as immigration between the two countries, are likely to be major sticking points.

Mr Jaitley said the economic relationship between India and UK was "extremely important".

"It works both ways, because the British invest a lot in India, Indians invest a lot in Britain," he said.

"There is a huge amount of movement of persons as far as the two countries are concerned.

"Both in manufacturing and in services I think there is already a relationship that exists, and therefore that is a relationship that will have to be carried forward and expanded further," he added.

Abrupt change

One of the most difficult issues between Britain and India has been immigration, with Indian business leaders and universities complaining that visa restrictions in the UK have limited the number of Indian immigrants coming to Britain.

Although not directly linking the issue to free trade, Mr Jaitley said that Indian immigration has been economically beneficial to Britain.

Customers in Ahmedabad waiting for a bank to open last December

"We certainly would be putting forward a point of view on this," Mr Jaitley told me.

"But historically, Indians move to Britain, both for education and for work, and have contributed a lot as far as the economy here is concerned.

"Our students in particular that used to come to the United Kingdom have contributed to, if not subsidised, the education system here, and I think it is evident to everyone that this number numerically has been coming down, so it is a concern to us.

"It should also be a concern to the United Kingdom," he warned.

On domestic issues, Mr Jaitley said the abrupt withdrawal of high denomination rupee notes was the only avenue open to the government, despite the short-term chaos that ensued.

He said there was "no other way" it could be done.

"The shadow economy was extremely large, the ratio of high denomination currency was very high and consequently its impact on corruption, tax evasion, on fuelling other crimes like terror - these are all the vices that came up," said Mr Jaitley.

"Therefore instead of giving an opportunity to the evaders to manage [the withdrawal] - because tax evasion creates an unfair advantage in favour of the evader as against the citizens of the country - it had to be done abruptly.

"Obviously there was a temporary period of 10-15 days where there were long queues [at banks as Indians sort to deposit cash or convert the notes they held to new denominations].

"[But] the queues shortened and I think eventually this was, in terms of remonetisation, one of the smoothest exercises of currency replacement, hugely welcomed by the people because it was the right cause," the minister said.