Why Australia's 457 temporary workers' scheme is attracting heat

- Published

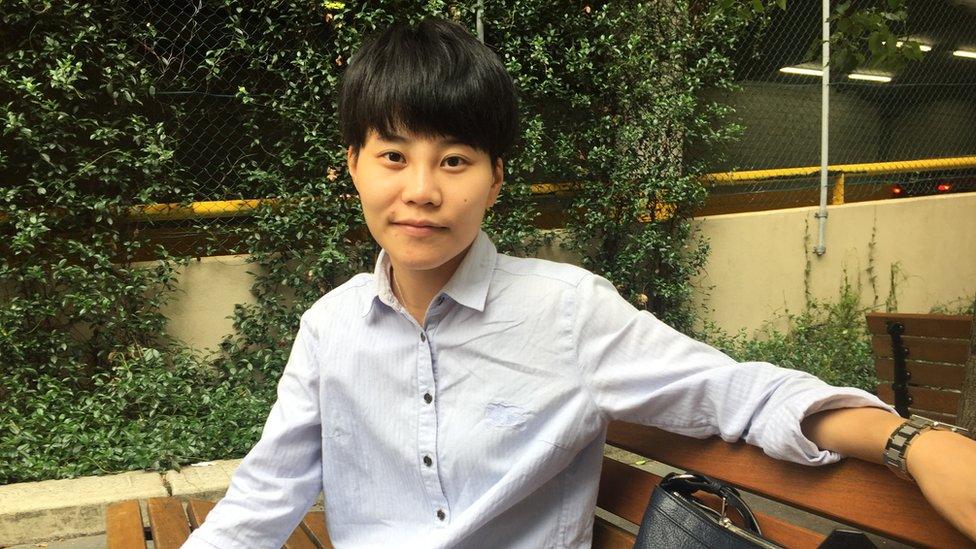

Renee Zheng sometimes feels guilty she might be taking a job from an Australian

The alleged exploitation of migrants, and fears that Australians are losing out to foreigners in the jobs market, have prompted the government in Canberra to signal reforms to its temporary overseas workers' scheme.

Known as the 457 visa programme, it allows employers to bring in staff from abroad if they can't find a suitably qualified Australian.

Designed to plug skills shortages, it includes more than 650 eligible occupations.

Among them are childcare centre administrators, tax accountants, architects, anaesthetists, motorcycle mechanics and gas fitters, while the most commonly recruited employees are cooks, cafe managers and marketing specialists.

Having previously said the government would "condense" the list, Immigration Minister Peter Dutton has now announced an end to the scheme for workers in the fast food industry, where more than 500 visas have been granted to foreigners in the last five years.

'Pay the price'

The 457 visa enables an IT worker from, say, Bangalore, along with her or his family, to stay in Australia for up to four years, provided they are sponsored by a business that can't fill the vacancy locally.

Other options, such as permanent migration, are open to tradespeople and professionals.

But it is the popular 457 visa system that is increasingly attracting political heat, and the Labor opposition leader Bill Shorten has warned Australia will "pay the price" if the flow of workers from other countries isn't stemmed.

"It is too easy to import our skills [rather] than train our people. And too many work visas are being used as a low-cost substitute for employing an Australian, not to address a genuine shortage," Mr Shorten cautioned.

Opposition leader Bill Shorten has been a vocal critic of the 457 programme

Most 457 visas are granted to migrants from India, the UK and China.

Twenty-eight-year-old Renee Zheng from the southern Chinese port city of Guangzhou works for Black Diamondz, a real estate agency in Sydney that sells property to wealthy Chinese buyers.

She told the BBC that she does at times feel guilty that she might be taking a job from an Australian, although it's not only a degree in marketing, but her language and Chinese social media skills that have made her an important part of the team.

"My company needs a specialist to know the Chinese market and the target audience," she says. "It is a little bit hard [for Australian firms] to find people who can speak Mandarin and can also speak Cantonese and English, to use the different digital media, like the WeChat platform in China, and Weibo."

Black Diamondz targets wealthy Chinese buyers, so having staff who can speak Mandarin or Cantonese is beneficial

Last year, Australia issued more than 45,000 of these types of permits - a drop of 11% from the year before.

Rossana Gonzalez, from Immigration Experts Australia, a Sydney-based migration agency, told the BBC that what should be a valuable economic tool has become too bureaucratic.

"A lot of our employers… are desperate because they cannot recruit from the Australian labour pool. It is imperative to our economy that the programme remains strong," she says.

"However, in the last 18 months we have seen a drastic decline in requests for 457 visa holders. I believe that a lot of employers are now scared off the process. The processing times are far too long. It leaves a lot of businesses and employees in limbo."

Dan Richardson feels that frustration. He swapped Brighton on England's south coast for Australia's Pacific seaboard when he was recruited on a 457 visa by a company in Sydney in 2011.

Brit Dan Richardson came to Australia on a 457 visa himself but says it is now more difficult to recruit people via the scheme

He now runs a digital marketing firm here and says that engaging essential staff overseas was increasingly being bogged down by red tape.

"The challenge is finding the right people," he says. "At the moment, in my line of work, it is becoming increasingly difficult to bring people in on 457s for the type of work that we do, so it feels like that is getting a little bit tougher."

Then there are fears that the system has been corrupted by unscrupulous bosses, who ignore their legal obligation to pay market wages, exploit migrants and deny Australians properly paid work.

Tony Sheldon, the head of Australia's Transport Workers Union, believes foreigners need more protection.

"The way to deal with this economic question about the exploitation and replacement of workers is by making sure overseas workers aren't exploited. If you are paid the same rates of pay, the likelihood of bringing in overseas workers is substantially diminished," he says.

Tony Sheldon says foreigners need more protection

Recalibrating such a large system to be more elastic and responsive to economic needs presents challenges. Many industries, including IT, and regional areas rely on 457 visa holders, while ministers will be well aware of voter anxiety about jobs being lost to foreigners.

The programme might not be perfect, but Raja Junankar from the University of New South Wales says that in many cases everybody wins - migrants get to enjoy the perks of a life down under, and Australia fills gaps in its labour force.

"People come from other countries on 457 visas because they get a decent job," he says. "Their conditions of work in Australia typically are better than many other countries from which they come. If you came from India or China, the working conditions in Australia are fantastic compared to that, so people would be in a very good position."

You can hear more on this story on Business Daily on Thursday, 2 March at 08:30 GMT

- Published2 March 2017

- Published21 January 2017

- Published1 June 2016

- Published22 June 2016