How an obscure seed is helping to save the elephant

- Published

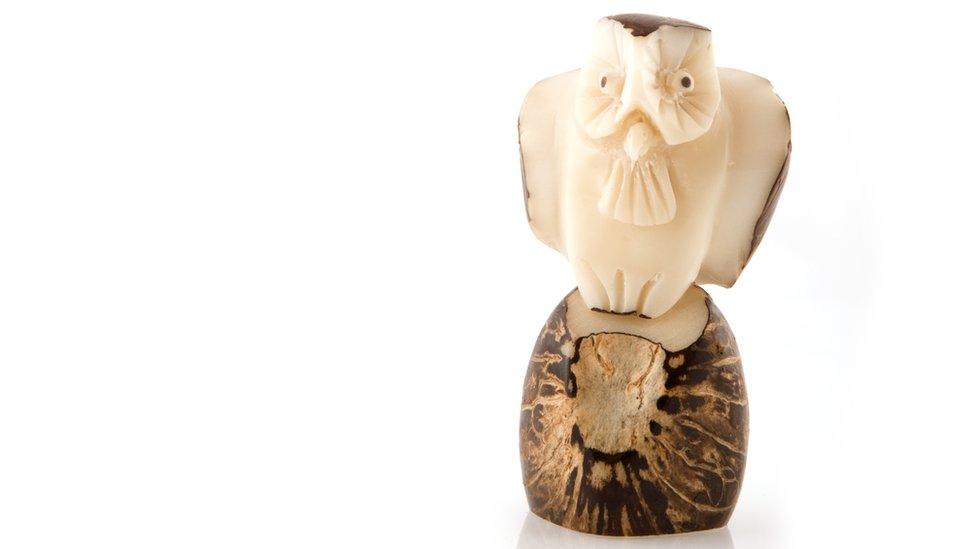

The tagua seed reaches 9cm (3.5 inches) in length, and can be carved like ivory

Onno Heerma van Voss jokes that he never intended to be a conservationist, but he is helping to save the African elephant.

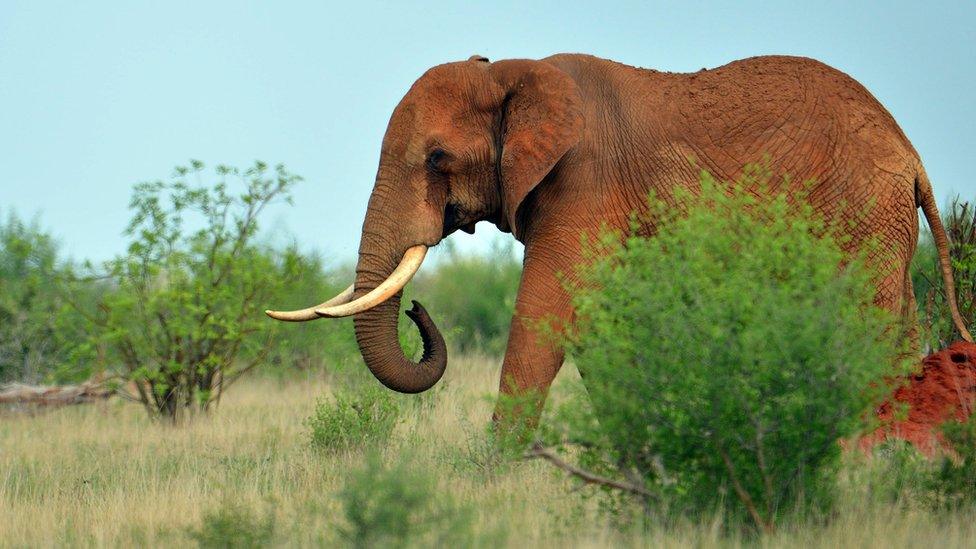

Numbers of elephants in the wild are still falling; it's estimated 100 of them are killed by poachers every day for their tusks to meet the continuing demand for ivory.

There are now only around 415,000 African elephants across the continent, down from as many as five million a century ago, according to global campaign group WWF (formerly known as the World Wide Fund for Nature).

While the worldwide sale of new ivory was outlawed in 1989, the animals are still being slaughtered to fuel an illegal trade led by continuing demand in China.

So what exactly is Mr Heerma van Voss, a 48-year-old Dutchman, doing to help protect the African elephant? He sells seeds.

Onno Heerma van Voss had never heard of tagua before he moved to Ecuador

Yes, you read that correctly, but these aren't any old seeds, they are instead rather special ones from South America called tagua.

They are the off-white coloured seeds of six species of palm trees. They can reach up to 9cm (3.5 inches) in length and when dried become very hard indeed. So hard in fact that they are also known as "vegetable ivory".

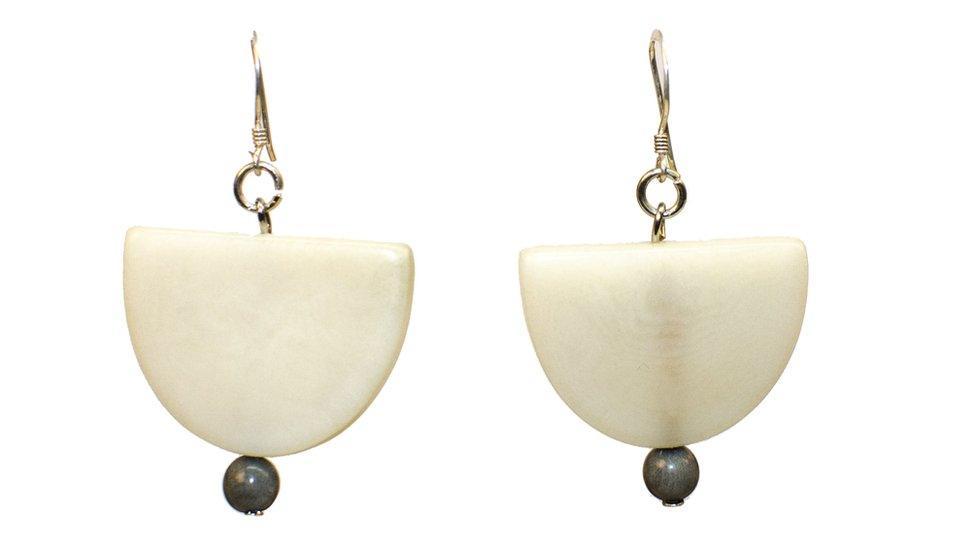

And like ivory, tagua can be polished and carved, and turned into ornate carvings or jewellery.

From his base in Quito, the capital of Ecuador, Mr Heerma van Voss's company Naya Nayon has been exporting tagua for 16 years, and he says that sales are booming.

Tagua has a very similar feel to ivory, but is a fraction of the price

He now sells to 70 countries, including China, Japan and Singapore, as tagua grows in popularity as an alternative to ivory.

And with China pledging to end its domestic trade in elephant tusks by the end of this year, Mr van Voss is hopeful that demand is going to jump even further.

Elephant plant

Using tagua as a substitute for ivory is nothing new. Indeed exports to Europe began in the 19th Century in order to meet the demand for an ivory-like raw material. This was used to produce ornamental items such as buttons, chess pieces, and decorative handles for canes.

In fact, the scientific name for the six species of palm trees that produce tagua is Phytelephas, which means elephant plant, a nod to the ivory-like quality of the seeds.

The white flesh of the tagua seed becomes exceptionally hard once it dried

However, tagua fell into obscurity, so much so that Mr Heerma van Voss had never heard of it when he first visited Ecuador in 2000.

Very much liking the country he decided to stay and set up a business, launching Naya Nayon to make and export wooden furniture. Then a year later he had a phone call.

"In the beginning of 2001, a France-based British lady contacted me if I could supply hand carved tagua figurines," he says.

The seeds are harvested from six species of palm trees

"Anyhow, you listen to clients to make a company work. So I did it, and I started to like the tagua and slowly it took off.

"I always joke that I am a forced ecologist, but I actually really like this product."

Tagua seeds - which have a brown outer husk - can be dried in the air, or in an oven

Mr Heerma van Voss now sells $200,000 (£160,000) worth of tagua per year that he buys from farmers. He and his four members of staff dry and slice the seeds ready to be turned into jewellery, with France being his largest market.

The sliced tagua typically retails for $30 a kg, while the raw seeds sell for $6 a kg. By contrast, a kilogramme of ivory is worth as much as $1,100 in China.

While Mr Heerma van Voss is preparing for a big upturn in exports to China, tagua does face two hurdles in the country.

The seeds can be dyed into any colour required by a jeweller

Firstly, even the longest tagua seeds are much shorter than the average elephant tusk, which limits the size of the ornaments that can be made from the material. And secondly, it lacks ivory's exclusivity.

Hongxiang Huang, a Chinese journalist and anti-ivory campaigner, explains: "As people become wealthier they want to buy luxury items, and ivory is one of the many things that people desire. This is the situation in China."

Hairy tale

For buyers wanting an alternative to elephant ivory that still comes from a mammal but is ethically sourced, the answer comes from under the frozen Siberian tundra in the north east of Russia.

It may sound bizarre, but the tusks from woolly mammoths that died tens of thousands of years ago are mined on a regular basis. While official figures are not available, an estimated 60 tonnes of mammoth ivory is harvested each year.

Mammoth tusks can be used as a substitute for elephant ivory

Mammoth ivory sold for an average $350 a kg in 2014, according to the charity Save the Elephants. This is about a third of the price of elephant ivory, but giant mammoth tusks in good condition can fetch far more.

John Frederick Walker, an expert on ivory, says: "Master carvers tend to prefer elephant ivory because fresh elephant ivory is easier to carve.

"But in fact, you can make wonderful things from mammoth ivory."

Yet with tagua far easier to get hold of than mammoth ivory, and considerably cheaper, it is the South American seeds that is increasingly being used by jewellers, and not the Siberian tusks.

Demand for tagua in China is expected to rise after the ivory ban comes into place

Marion Andron is co-owner of French jewellers Nodova, which sold more than 300,000 euros ($320,000; £256,000) of tagua jewellery last year.

Ms Andron, 27, travels to Ecuador twice a year to oversee the production of the tagua that is done by seven local women at a cooperative.

While Nodova's largest markets are France and the UK, it sells to stores across Asia and Ms Andron says that the forthcoming blanket ban on ivory sales in China offers a huge opportunity.

"I think tagua has helped diminish the demand for animal ivory, and I honestly don't think someone today can be ignorant about the slaughter of elephants with all the media coverage," she says.