Has this dress been to more countries than you?

- Published

This Zara dress had been to at least five countries before it ended up on a shop hanger

"Made in Morocco" says the label on the pink Zara shirt dress.

While this may be where the garment was finally sewn together, it has already been to several other countries.

In fact, it's quite possible this piece of clothing is better travelled than you. If it was human, it would have certainly journeyed far enough to have earned itself some decent air miles.

The material used to create it came from lyocell - a sustainable alternative to cotton. The trees used to make this fibre come mainly from Europe, according to Lenzing, the Austrian supplier that Zara-owner Inditex uses.

These fibres were shipped to Egypt, where they were spun into yarn. This yarn was then sent to China where it was woven into a fabric. This fabric was then sent to Spain where it was dyed, in this case pink. The fabric was then shipped to Morocco to be cut into the various parts of the dress and then sewn together.

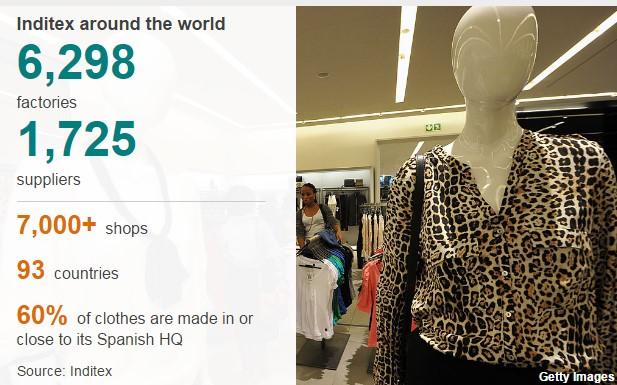

After this, it was sent back to Spain where it was packaged and then sent to the UK, the US or any one of the 93 countries where Inditex has shops.

From dresses to t-shirts and trousers, most items of clothing sold around the world will have had similarly complicated journeys.

In fact, they're likely to be even more convoluted.

Most Inditex garments are made close to its Spanish headquarters or in nearby countries such as Portugal, Morocco and Turkey.

This is what helps the firm achieve its famously fast reaction times to new trends.

Most of its rivals' supply chains are far less local.

Regardless of where they're based, most factories are not owned by the fashion brands that use them. Instead, they're selected as official suppliers. Often these suppliers subcontract work to other factories for certain tasks, or in order to meet tight deadlines.

Your cotton top may well have started out in a field in Texas before criss-crossing the globe

This system can make tracking the specific origins of a single item difficult. I contacted several big clothing brands including H&M, Marks and Spencer, Gap and Arcadia Group last week to give me a sample example of the journey of a t-shirt in their basic range from seed to finished product.

Only Inditex was able to respond in time to meet the deadline for this article.

"I imagine companies don't want to respond because they have no clue where the materials they buy come from," says Tim Hunt, a researcher at Ethical Consumer, which researches the social, ethical and environmental behaviour of firms.

The difficulties were highlighted devastatingly by the 2013 Rana Plaza disaster where more than 1,100 people were killed and 2,500 injured when the Bangladesh garment factory collapsed.

In some cases, brands weren't even aware their clothes were being produced there.

The #whomademyclothes campaign encourages customers to put pressure on fashion firms to be more open about their suppliers

According to the "Behind the Barcode" report, external by Christian Aid and development organisation Baptist World Aid Australia, only 16% of the 87 biggest fashion brands publish a full list of the factories where their clothes are sewn, and less than a fifth of brands know where all of their zips, buttons, thread and fabric come from.

Non-profit group Fashion Revolution, formed after the Rana Plaza factory collapse, is leading a campaign to try to force firms to be more transparent about their supply chains.

Every year, around the time of the disaster it runs a #whomademyclothes campaign encouraging customers to push firms on this issue.

Fashion Revolution co-founder and creative director Orsola de Castro says the mass production demands of the fashion industry and the tight timescales required to get products from the catwalks on to the shelves as quickly as possible means the manufacturing processes have become "very, very chaotic".

"The amount of manpower which goes into the production of a t-shirt - even at the sewing level, it goes through so many different hands. On their standard products most brands wouldn't know the journey from seed to store," she says.

While newer and smaller fashion brands are creating products with 100% traceability, she says it's a lot harder for the established giants.

"It's a big and complex issue to turn around and would require a massive shift in attitude."

Pietra Rivoli travelled from the US to China and Africa to track the journey of a single $6 t-shirt

Yet just over a decade ago, Pietra Rivoli had no problems tracking the journey of a single $6 cotton t-shirt she'd picked out of a sale bin in a Walmart in Florida.

Starting with the tag at the back of the t-shirt, she tracked its journey backwards from the US "step by step along the supply chain".

"A shoe leather project," is how Prof Rivoli describes her journey, which resulted in a book, The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy.

As a teacher of finance and international business at Georgetown University in Washington, Prof Rivoli wanted to investigate her assumption that free trade benefited all countries.

Pietra Rivoli says the current backlash against global trade is linked to political interference

Her travels took her from the cotton-growing region of Lubbock in Texas to China, where the t-shirt was sewn together. Eventually, she ended up in Tanzania on the east coast of Africa, which has a thriving second-hand clothing market.

Her assumption was that the complicated supply chain was driven by cost and market forces.

She concluded that a lot of brands' decisions about where to buy supplies and make their clothing was actually driven by politics. She cites US agricultural subsidies for cotton growers and China's migration policies encouraging workers to move from the countryside as examples.

"Rather than a story of how people were competing - how do I make a faster T-shirt, a better T-shirt, a cheaper T-shirt - what I found is that the story of the T-shirt and why its life turned out the way it did was really about how people were using political power," she says.

The current backlash against global trade is a direct result of this kind of political interference, she believes.

This kind of consumer anger could eventually drive change among fashion firms, she says. Prof Rivoli notes that many firms now list all their direct suppliers and she says there is a move towards developing fewer, longer term supplier relationships.

"There might be a little less hopping around," she laughs.