Is inflation all down to Brexit?

- Published

- comments

Slowing real income growth could be a challenge for the Prime Minister

It was Harry S Truman who famously pleaded for a one handed economist, so tired was he of proponents of the dismal science saying "well, on the one hand, sir... but on the other..."

Sadly for the 33rd President of the United States, you would need a lot of hands to explain today's surprisingly rapid increase in inflation.

Rising global commodity prices are pushing up inflation pressures around the world.

As global growth strengthens, that upward pressure is likely to increase.

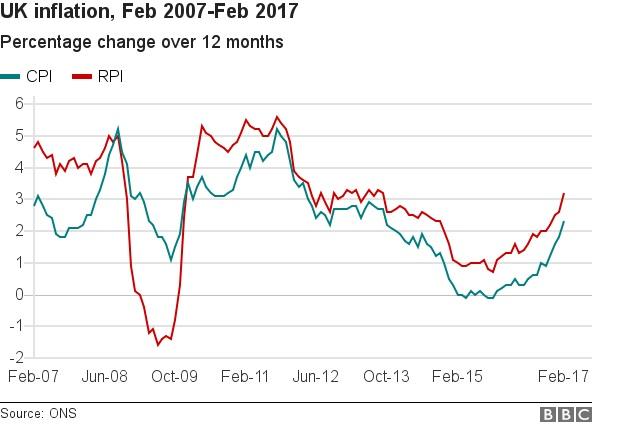

In 2015 and early 2016, we saw a period of deflation - falling prices - in key sectors such as fuel and clothing, so the rise now (in comparison with a year ago) is particularly stark.

More recently, poor weather in southern Europe has meant that foods such as salad have increased in price by over 60%.

Although, as Alan Clarke from Scotia Bank, points out, "the lettuce crisis didn't cause today's big upwards surprise."

Prices for lettuce and other vegetables rose as supermarkets were forced to ration them

What did were increases in the prices of food (the first year-on-year rise for more than two years), fuel and what are described as "recreational" goods (such as televisions and laptops).

These increases can all be linked, at least in part, to the cost of importing goods into the UK.

And a large part of that increase in cost comes from the fall in the value of sterling since the referendum.

Although it is always worth pointing out that sterling's fall was evident before the referendum (many economists argue it was over-valued) and that the dollar has been particularly strong as the Federal Reserve raises interest rates.

Interest rate rise?

Will the increase in inflation continue and put pressure on the Bank of England to raise interest rates?

Well, input prices - what manufacturers pay for the materials and fuel they use - are rising by over 20% a year, the fastest since 2008.

And those costs will increasingly be pushed through to consumers.

So in the medium term, inflation is on an upward trajectory and could peak above the Bank's own forecast of 2.7% in the first three months of next year.

But, and it is a significant but, wage growth (a long-term motor of inflation) is actually slowing.

Last month, incomes grew by 2.3%, significantly down on a month earlier and the same number as today's inflation figure.

Wages squeeze

Yes, it is only one month's data, but as it stands, real income growth has stalled and groups such as the Resolution Foundation believe it will now turn negative.

The great wages squeeze which followed the financial crisis could well have returned.

And that is a worry for Theresa May, as I wrote last week.

Given that trend, the dovish position of the Bank is likely to remain in place.

Yes, the markets have upped their expectations of a rate rise, but the Bank has been clear: a cut to support economic growth as the UK begins its Brexit negotiations is as likely as an increase.

And any increase, if it were to come, is likely to be small.

Which is bad news for savers, of course.

It would be ridiculous to say that Brexit is not affecting the UK's course on inflation.

But it is not the whole story. To tell that, you need plenty of hands.