What might F1's new owners do to rev up the sport?

- Published

Game faces on: The drivers are gearing up for the new season

Much has changed in Formula 1 since Lewis Hamilton took the chequered flag at last year's season finale in Abu Dhabi.

The reigning world champion, Nico Rosberg, has walked off into the sunset. The cars have evolved, with new rules allowing them to become bigger, faster and more aggressive-looking.

But the most significant transformation has taken place behind the scenes.

Formula 1 is under new ownership. Control has passed from private equity firm CVC Capital Partners to the US group Liberty Media.

As a result, former chief executive Bernie Ecclestone, the man who is credited with turning F1 into one of the world's most lucrative sports, has finally stepped down at the age of 86.

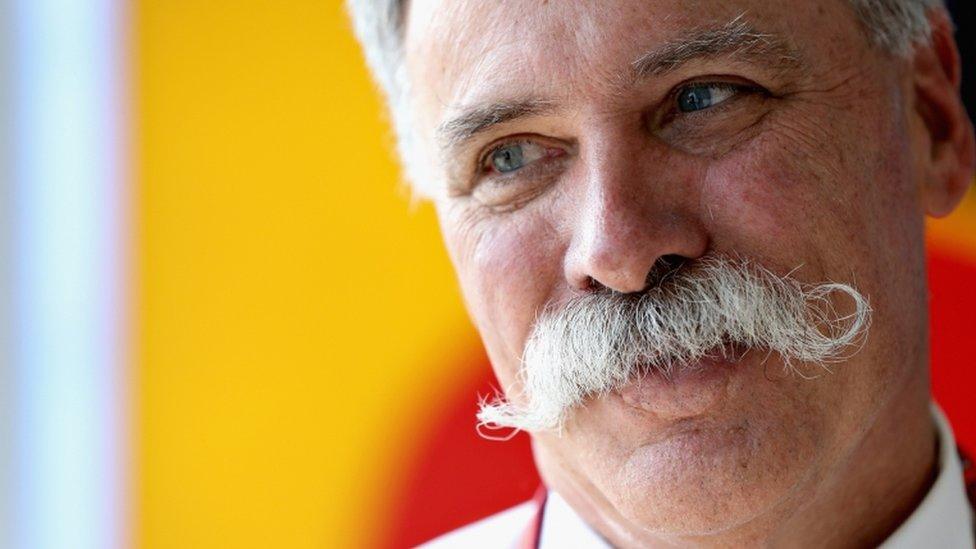

The new chief executive is Chase Carey, a veteran of the US media industry and a former associate of Rupert Murdoch. He has already suggested that F1 "needs a fresh start".

Audiences falling

So what might actually be changed?

In commercial terms, Formula 1 is a curious beast. It is certainly lucrative. In 2015, its revenues reached $1.7bn, according to motorsport analysts Formula Money. Yet teams towards the back of the grid often struggle to make ends meet.

Ferrari is well-funded under the current system

Earlier this year, the Manor team finally closed down after several years of financial problems. Its collapse followed those of HRT and Caterham, who folded in 2012 and 2014 respectively.

And even as revenues have been rising, TV audiences have been falling.

The sport claimed 400 million viewers in 2016, down from a peak of 600 million in 2008. That may be partly due to a shift towards pay-TV in major markets such as the UK, Italy, France and Spain.

Extra bonuses

Formula 1 is an expensive business: even the smallest teams employ about 200 people, and it costs at least $100m just to get on to the starting grid. Remaining there, however, is the biggest challenge.

Small squads that don't win races and that don't get much television airtime often struggle to raise the sponsorship they need.

And although roughly half of F1's revenues are distributed among the teams, they are not divided equally.

Part of this is merit-based. The higher you finish in the World Championship, the more money you get. But some teams get extra bonuses, irrespective of how well they perform.

Smaller teams like Sauber want to see F1 revenues distributed more evenly amongst the teams

Ferrari, McLaren, Red Bull, Mercedes and Williams all get extra funding. And Ferrari gets more than $60m simply for turning up, because of its place in the sport's heritage.

The smaller teams think this is deeply unfair and argue that because in F1, success is heavily linked to financial resources, it distorts the competition. In 2015, the Sauber and Force India teams lodged a formal complaint, external with the European Commission.

Sauber team principal Monisha Kaltenborn says she hopes matters will change under Liberty Media.

Talks so far, she says, have been "very encouraging". Although altering the way payments are made would inevitably mean some of the larger teams getting less, she thinks they will co-operate.

"Why shouldn't it happen?" she says. "The big teams know that the show has to be a healthy show.

"If viewing figures continue to go down and we don't have that 'aha effect', sponsorship will go down and they will suffer equally, probably more, because they need more money to keep their operations going."

'Skill rewarded'

Graeme Lowdon, a motor racing entrepreneur who helped to found the Manor team, agrees that a more level playing field is needed,

"What people want to see in F1 is a sport where skill is rewarded," he says.

"The sports that have grown in the past few years are the ones that are focused on parity, such as the NFL."

Nico Rosberg retired days after winning his first F1 world title

Another area where change may be needed is in how F1 reaches out to its fanbase.

In recent years, the sport has focused on maximising its revenues, but despite expanding into new markets, it has arguably failed to attract a new generation of enthusiasts.

Races have been held in countries with little or no F1 heritage or established audiences, but where governments have proved willing to pay ever-higher sanctioning fees in exchange for the glamour associated with hosting a grand prix.

At the same time, fewer events have been held in the sport's European heartlands, where organisers are less willing to pay more than $30m for the privilege.

Liberty Media appears keen to reverse that trend and introduce new races in the United States, in an effort to broaden the sport's appeal.

Chase Carey has taken over at the helm of Formula 1

That could mean getting rid of lucrative but controversial events like the Azerbaijan Grand Prix, which Liberty Media's chief executive Greg Maffei recently said "does nothing to build the long-term brand and health of the business".

However, according to Formula Money's Christian Sylt, that strategy may not work if F1 wants to keep its revenues at their current level.

"I do not believe there is a 'big ticket' alternative revenue stream to race hosting fees", he says.

'Just not exciting'

But perhaps the biggest challenge of all is to bring in a new generation of enthusiasts.

"We need to do something to connect with younger fans," says Sauber's Monisha Kaltenborn. "You know, we don't want people who are just 40-something watching the sport. We have to go into digital media and social media far more.

"That's not a question about instantly making money, but it's about positioning yourself towards young people, so that tomorrow they'll come and watch a race."

Can F1 under Liberty Media succeed in attracting younger fans?

Former Jordan team commercial manager Ian Phillips puts it even more bluntly. "At the moment Formula 1, it hurts me to say it, is just not that exciting," he says.

The problem, he thinks, is cost. Champions Mercedes spend upwards of $400m a year on their cars, and other teams simply can't compete. So the racing becomes boring.

"I have a 13-year-old son who just watches the first lap, then he goes away," he says.

So wealthy F1 may be - but if it can't attract the kids, it may well find itself overtaken by other, more appealing sports before long.

You can hear more on this story on Business Daily: Financing Formula 1