The wine detective battling counterfeiters

- Published

Philip Moulin is head wine detective at wine merchant Berry Brothers & Rudd

Philip Moulin intently studies the label on a bottle of expensive wine with a magnifying glass.

He then shines a blue ultraviolet light at the bottle, before picking it up and weighing it in his hands.

"Counterfeit bottles can often be much lighter," he says.

Mr Moulin is standing at his workbench at the main warehouse of UK wine merchant Berry Brothers & Rudd (BBR).

A cavernous facility in the Hampshire town of Basingstoke, more than 2.7 million bottles of wine are stored there at a constant 12C, stretching from floor to ceiling in endless rows.

Mr Moulin uses a UV light to spot security marks on legitimate bottles

While Mr Moulin's official job tile is "fine wine and authentication manager", he is in fact BBR's head wine detective, tasked with preventing any counterfeit bottles entering the facility.

It is a vital role at BBR because the company is one of the world's largest sellers of fine wines, the very expensive bottles that can retail, external for more than $10,000 (£8,000).

And as demand for fine wine has soared over the past 20 years, fuelled by China, fraudsters are unfortunately continuing to target the industry.

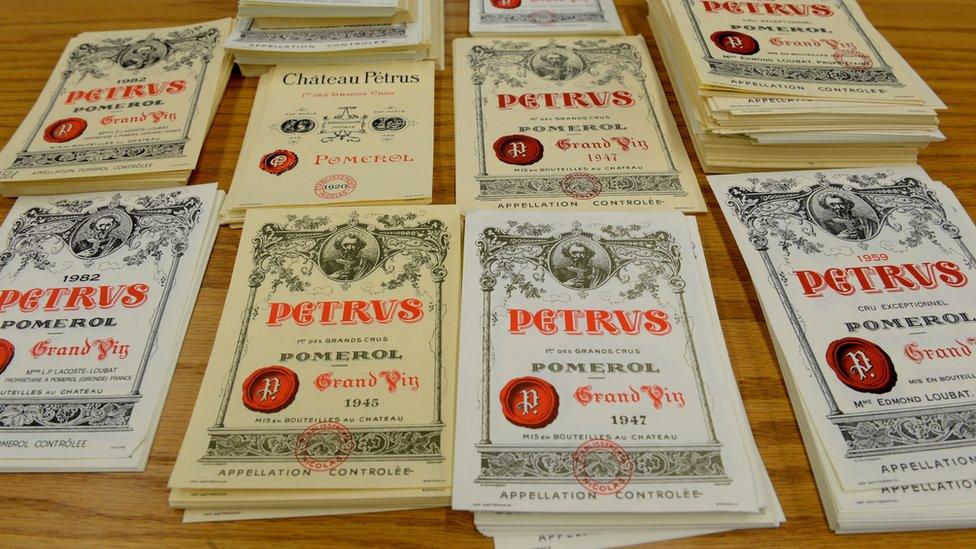

In the most high profile example of recent years, a man called Rudy Kurniawan was jailed for 10 years in California in 2014 after being found guilty of making and selling fake wines.

Rudy Kurniawan made counterfeit bottles of red wine - such as these - for more than 10 years

At his home in Los Angeles he created a counterfeiting workshop where he would make fake versions of famous and rare bottles, using labels he printed out, and filling old bottles with cheaper wine.

The Indonesian national, who was 37 when he was sentenced, was so skilled at the ruse that according to some estimates he faked more than $500m of wine between 2002 and 2012.

With some of Mr Kurniawan's bottles said to still be floating about on the global fine wine market, as well as those made by other fraudsters, Mr Moulin aims to stop any of them getting into BBR's facilities.

"There is not a problem with the wines we buy as a company, but where we have to be very careful is the wines that our customers buy from auctions or elsewhere, and then pay to store with us, and/or sell via us. That's the really potentially tricky stuff," he says.

BBR's main warehouse is home to 2.7 million bottles of wine

"We check these bottles and their paper trail, vigorously when they come in... about 200 cases a week.

"I have two men in my team who check the bottles first. We are looking at everything from the labels, to the weight of the glass, the capsule (that covers the top of the bottle), and the depth of the punt (the indent at the bottom of the bottle).

"If the lads aren't sure they give me a shout, and if I'm not sure we panic."

Mr Moulin says that he and his team intercept a fake bottle "once every two or three months" and then immediately inform the owner.

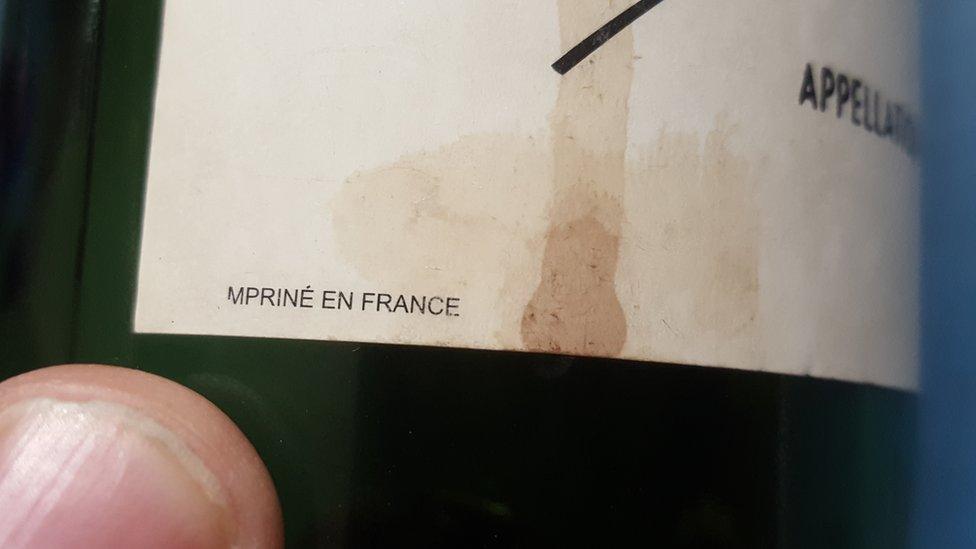

This label is fake because it should say "imprime" with an "m" not "imprine" with an "n"

"We ask them to come and collect the bottle or bottles asap," he says.

"As far as we are concerned, we are doing them a favour, but people get really upset about it - no-one likes to think they have been taken for a ride."

The wines most often targeted by counterfeiters are those from the top producers in the French wine regions of Bordeaux and Burgundy, especially from highly coveted older vintages, stocks of which are now limited.

These wines are typically sold by auction, and auction house Sotheby's is one of the industry's biggest players. Last year it sold $74m of fine wine, external, a 22% increase on 2015.

Mr Moulin and his team break into wooden cases of fine wine to check each bottle

Jamie Ritchie, worldwide head of wine at Sotheby's, says the company has stringent procedures in place to prevent any counterfeit bottles being auctioned.

"We train all our specialists to determine the authenticity of bottles, matched to appropriate provenance, and always have two or more senior specialists review high-value bottles," he says.

"We use high-powered magnifying camera loupes to review labels, and our internal library of resources to research authenticity issues. Where required, we research the provenance, which includes contacting the producers."

Wine counterfeiters will often reuse old corks

Wine blogger Jamie Goode says that fraud remains "a massive problem" for the industry.

Regarding counterfeit bottles, he says that when it comes to very old bottles, the weakness is that "so few people have got any frame of reference as to how the real wine should taste".

"For example, it is said that the 1945 vintage of Mouton Rothschild (one of the finest red wines from Bordeaux) was incredible, but very few people alive have actually tasted it. That is what Rudy Kurniawan was manipulating.

"If you are ever buying fine wine, only go to the most reputable of auction houses, and don't settle for any vague answers regarding provenance."

Counterfeiters will make fake labels

With fine wine being so valuable fraudsters are not just producing counterfeit bottles, they are also using fraudulent means to try to steal genuine bottles, as London Michelin-star restaurant Pied a Terre found to its cost a few years ago.

Owner David Moore says that the wine fraudster pretended to be working for a wealthy Russian.

"We had a phone call, late at night, apparently from a party organiser, who said that his Russian client was out of Cristal (a very expensive champagne), and could we help," says Mr Moore, Pied a Terre's owner.

The tools of Mr Moulin's trade

"He said it didn't matter what the cost was. A very naive member of staff thought he was doing a good deed and put the sale through the till, three magnums at £1,200 each. And all seemed fine.

"A taxi driver then turned up to collect the champagne... and of course a few days later the credit card company refused to pay - the card had been stolen. It was a real schoolboy error on our part.

"Now no bottle leaves the restaurant without a debit or credit card being pushed into a chip-and-pin machine."

As blogger Jamie Goode puts it: "If you are buying or selling wine, and it looks too good to be true, then it probably is."