Trump's trade agenda: Just what are his priorities?

- Published

Trade was one of the dominant themes in Donald Trump's election campaign.

He often focused on particular US trade partners. Mexico and China were most frequently in his sights.

And one of his first actions as president was to withdraw the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a regional trade deal, agreed by his predecessor but which had not come into force.

So what are President Trump's priorities for trade? What does he hope to achieve?

He often focuses on trade imbalances: the US deficit in trade with the rest of the world and bilateral deficits too.

Here are some figures, external. Last year the US had a deficit of half a trillion dollars in trade in goods and services with the rest of the world. For China, the bilateral deficit was close to $350bn (£280bn). For Japan, Germany and Mexico, the figures were in the range of $60-70bn.

President Trump considers these figures to be evidence that the US has done badly, that it has been treated unfairly.

Mexico, he has said, external, is "killing us on jobs and trade".

He has expressed similar views on China: "We are like the piggy bank that's being robbed."

His trade adviser Peter Navarro told the Financial Times that Germany uses a grossly undervalued euro to exploit its trade partners, essentially arguing that the exchange rate gives Germany a competitive advantage that's unfair.

Mr Trump has also criticised Japan for barriers to American car exports and for manipulating its currency to gain a competitive advantage.

He wants to see a reversal of the decline in manufacturing employment that the US has experienced. (The number of jobs in manufacturing, external dropped sharply in the 2000s, though the share of total employment, external has been falling for decades.)

So where do those concerns lead President Trump's trade agenda?

Rolling over?

His bilateral discussions have got off to a somewhat gentler start than his campaign language might have led us to expect.

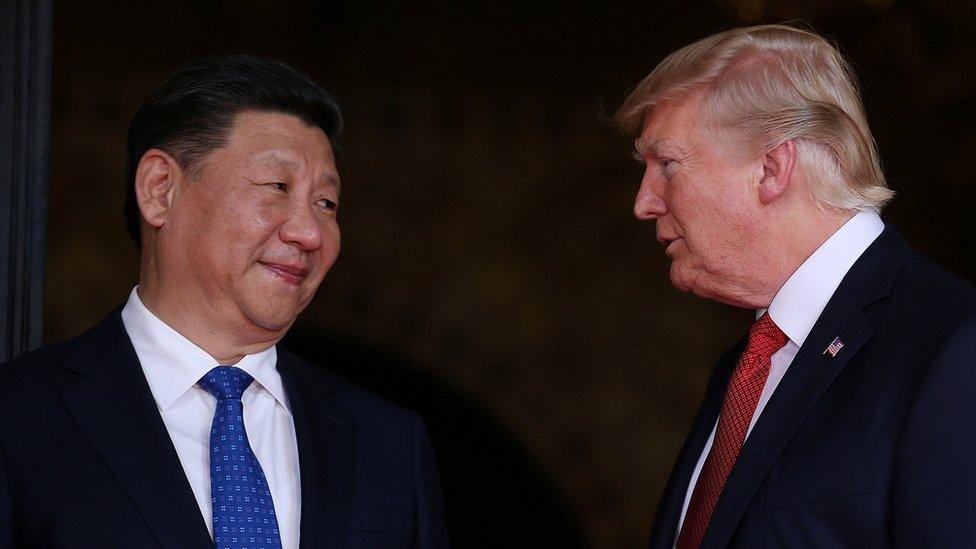

He held a summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping last weekend.

Mr Trump said "tremendous progress" had been made in talks with Mr Xi

They agreed a 100-day programme of talks. The US expects China to offer better access to its market, including for beef and services companies. Mr Trump's campaign language about possibly imposing large tariffs on imports from China, as much as 45%, was not on display this time.

One China critic in the US, Gordon Chang, asked, external: "Did Trump just roll over on China trade?"

And just days after meeting President Xi, Mr Trump said his administration would not label China a currency manipulator, rowing back on a campaign promise.

China's critics have a wide-ranging list of allegations about unfair practices - subsidies to Chinese industries, dumping underpriced goods, and the theft of patents and copyright.

With Mexico, President Trump wants to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta), a deal that dramatically reduced barriers to commerce between the US, Mexico and also Canada.

Most goods are traded free of tariffs (taxes applied only to traded goods).

He has said that Nafta was the worst trade deal the US has ever done, that it kills American jobs. How would he like to change it? He has threatened a number of carmakers with "border taxes" (that is tariffs) if they expand production in Mexico for export to the US market.

Donald Trump is not popular in Mexico

That would be inconsistent with Nafta as it currently stands and it's hard to see how it would comply with any amendments to Nafta that the Mexican government would be willing to accept. It's also almost certain that such action would be incompatible with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

Revise, not scrap

But there are signs that the administration's approach may in the event be softer. There is a draft letter from the administration to Congress setting out objectives for a renegotiation. National Public Radio described the proposed changes as "tweaks", external.

There is quite a long list of areas proposed for revision, including a right to re-impose tariffs (probably temporarily) in response to a surge in imports and an effort to remove barriers to US exports to the other two countries.

There is also a call to look at what are called "rules of origin", which specify how much of a product's value has to be added in the Nafta area to qualify for tariff-free treatment. A higher threshold could make it harder to use components made in China, for example.

But what is clear is that this is about revising rather than scrapping Nafta.

It's also unclear exactly what Mr Trump would do about disputes in trade with other countries.

Options include making more aggressive use of the WTO's rules for disputes. There is its judicial dispute settlement system, and there are actions that countries can take unilaterally against subsidised or dumped imports (sold abroad more cheaply than in the producer's home market), provided they do it in a way that is set out in WTO rules.

Anxiety

What worries many trade experts is that the Trump administration might be ready to bypass WTO rules and impose new barriers to imports regardless of the organisation's rules. It would be a very serious, possibly fatal blow for the credibility of the agency if the world's largest economy were not to take it and its rules seriously.

Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin at the recent G20 meeting; the G20 dropped an anti-protectionist commitment after opposition from the US

The WTO is at the heart of a system of international trade relations, based on rules that started to take shape soon after World War Two. Although the WTO itself wasn't established until 1995, much of the rulebook that it now manages goes back to the late 1940s.

There is a lot of anxiety among trade officials about just how the global trade system might unravel if the WTO were seriously undermined. The concern is that there could be widespread new restrictions arising and their view - shared by the great majority of economists - is that increased trade protectionism would be bad for living standards around the world.

It certainly caused a lot of anxiety when a recent meeting of finance ministers from the G20 leading economies dropped from its communique a remark that had previously been routinely included about avoiding trade protectionism, something that was done at the insistence of the US delegation.

So we certainly have some new questions about what role the US will take in shaping the future of the global trading system.

President Trump's most strident campaign comments haven't yet been fully reflected in the actions of his administration, with the exception perhaps of the withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership. But it is still very early days.

- Published18 March 2017

- Published16 December 2015